Breaking News! Experts Say That Being Alive Causes Autism

(April 26, 2013, Albatross University) — In a dramatic new breakthrough, researchers have concluded that autism is caused by being alive.

“This is a great day for medical science,” said Dr. Ernest Eagerly, Director of the Department for the Medicalization of Humanity at Albatross University. “Our research team sorted through a myriad of studies linking autism to everything from pet shampoo to freeway traffic to creases in the placenta. After controlling for variables in the research such as usefulness, rationality, shameless self-promotion, and general hysterical posturing, we determined that all of the studies had one thing in common: people with autism are alive.”

But that’s not all, according to Dr. Eagerly. “Not only are people with autism alive, but their parents are also alive — a clear and dramatic indicator of an underlying genetic mechanism. This new understanding opens up exciting avenues for treatment and cure. If we can locate the gene that controls for being alive, we might just crack the autism puzzle once and for all.”

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that has stolen the souls of 1 out of 88 adorable children who otherwise look completely human. There is no cure.

While the latest research findings are dramatic, experts caution the general public that it’s important to be circumspect. “Being alive takes many forms and one has to be on guard against them at all times,” said Jenny McWhatsHerName, spokesperson for Only My Generation! (OMG!), an organization dedicated to the proposition that an epidemic of aliveness began with the development of vaccines. “Aliveness is not just a simple question of breathing,” she said with a giggle. “I mean, duh! You can’t simply hold your breath until you pass out and think that you’re going to be able to beat this autism thing! Laughing, loving, feeling at ease with your life — these are all warning signs.”

What’s the bottom line, according to OMG!? “Be afraid,” she said. “Be very afraid.”

Dr. Eagerly agrees. “We have found that the best defense against a diagnosis of autism is to sit completely skill and live in abject fear. I know it seems extreme,” he added, “but what’s the alternative? Enjoying your life? That will only result in hordes of people with autism being released upon an innocent and unsuspecting public.”

Because the only known remedy for being alive is dying, researchers stress that a cure may not be in the offing for several years. “It’s a tricky situation,” said Dr. Eagerly. “How do we separate autism from being alive, when the two are so closely linked?” He lauds the efforts of organizations like “OMG!” that suck the will to live right out of autistic people and their families.

“These organizations are on the cutting edge,” he said. “Just keep sending them your money.”

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

I Am So Sick Of Autism

Yes, I’m sick of autism.

No, I’m not sick of Autism the Condition. That I can live with, although it’s a complete pain in the ass sometimes. But what isn’t?

So that’s not what I mean. I’m talking about everything that isn’t actually the condition:

Autism The Event.

Autism the Tragedy.

Autism the Gift.

Autism The Epidemic.

Autism the Blessing.

Autism the Puzzle.

Autism the Next Step in Human Evolution.

Autism the Reason to Pound People Over the Head Because My Life Sucks Worse Than Yours.

When it comes down to it, what am I really sick of? I’ll tell you: I’m sick of autism The Condition That Must Be Interpreted.

Do we really need one more study about what causes autism? Do we really need one more article about how people with autism rock your socks off? Can we stop with the inspirational memes about autistic geniuses Who Overcame The Odds And Beat Autism Into The Ground? Can we call a moratorium on posts about how autism is an Epidemic of Tragic Proportions Never Before Seen By Human Beings? Can we please, please, please stop talking about autism as though it’s actually a thing that stands alone from actual people?

I know I’m old and jaded. Well, no, not really. Yes, I’m old. But I’m not jaded. I’m the opposite of jaded. I long for the time before autism was A Thing. I grew up before autism was A Thing. I grew up just being, you know, a kid. Just a kid. A kid with lots of what are now politely called issues, most of them unarticulated, but just a kid. I played baseball. I climbed trees. I stayed up till all hours. I read lots of books. I was quiet. I was kind. I had lots of plans for the future.

It would have been good to have articulated my issues. Seriously. I wish someone had helped with that. I wish someone had taught me how to take care of the body and mind that I had been given, rather than the body and mind that everybody thought I’d been given. I wish someone had given me a language for the particulars of how my mind and body work so that I wouldn’t spend the next 50 years of my life driving myself into the ground.

Really. I do wish for all that.

But I am so, so glad that autism wasn’t A Thing then. So glad. Because now it’s A Thing — A Thing that shadows me wherever I go. A Thing that I have to decide to disclose or not. A Thing that’s like a big box that I’m supposed get in and stay in and say This is Me. I often wonder who made that box, and I often wonder why they made that box, and I often wonder why people spend so much damned time talking about that box, worrying about that box, describing that box, and making money off that box — and spend so little time listening to and providing support to the people they’ve put in that box.

And sometimes, I wonder how the hell I even got in that box at all. I don’t recall that box even being there for the first five decades of my life. Did it just grow up around me and enclose me? Or did I jump into it, not realizing how hard it would be to get out — not realizing how hard it would be to say, in a world of boxes, that boxes feel suffocating?

My therapist in Brattleboro used to say that all labels are a box. Labels can be useful — for services, for finding kindred spirits, for getting support. But when it comes down to it, the support really needs to be about very particular things, not about the box, because all of us have very particular needs. None of us look like what’s advertised on the outside of the box — not completely. For me, the main disability is auditory. For someone else, it’s tactile. For someone else, it’s multi-sensory. For someone else, it’s a whole other constellation. You can’t put all that on a box, no matter how big it is. The label will always be a vast oversimplification.

I’d like to get out of the box now.

I’d like to just be Rachel again.

Just Rachel. Rachel who needs quiet in order to hear. Rachel who needs clarity in communication. Rachel who sees word pictures in her mind. Rachel who loves organizing, and who has a passion for so many things, and who can focus like a laser beam on any of them. Rachel who never stops thinking. Rachel whose heart is broken by the world on a regular basis. Rachel who fiercely hopes for better.

That Rachel. The one I’ve always been. The one outside the box.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

More Ableism from Our Friends on the Left

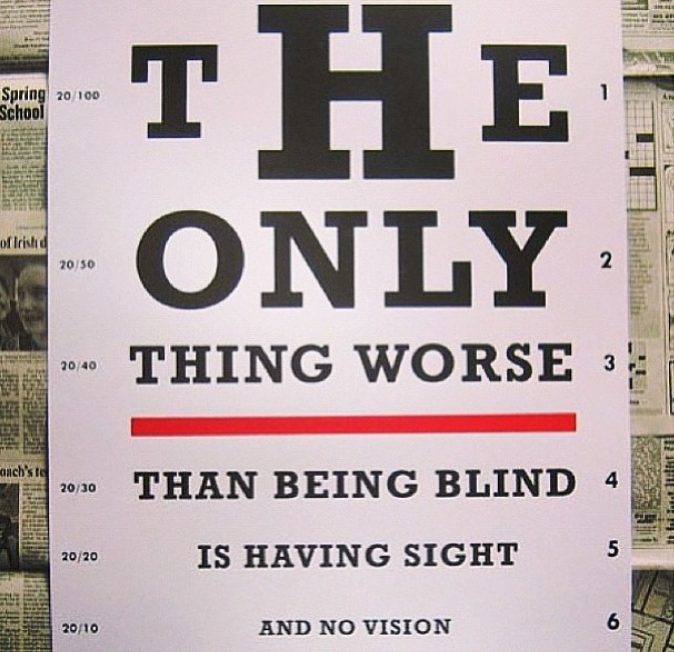

I just found this graphic on a Facebook page called Moving The Sun To Shine in Dark Places:

[The graphic shows an eye chart with the text "The only thing worse than being blind is having sight and no vision."]

It’s appropriate in this context to note that I spell out the text on the graphic in order to make the blog accessible to my blind readers. Because yes, indeed, my abundantly well-intentioned friends on the left: Blind people read. They even read blogs. On the Internet!

But I digress.

About your graphic… How can I put this? I’ll try to be as direct as possible: Using the word “blind” as a pejorative is not the way to go when you’re fighting for social justice.

Why? Okay, let me spell it out.

In this context, “blind” is entirely negative — nearly the worst thing that could happen to a person. And the people worse off? The ones who can literally see, but who have no vision for making the world a better place. Thus, blind people are just one tragic step above people who are too cowardly, or too selfish, or too morally bankrupt to care whether the world goes to hell in a handbasket.

You see, you lost me when you attempted to inspire people to moral action by appropriating the experiences of disabled people and attempting to speak in their voices. You looked at blind people and assumed that blindness is a tragic condition, roughly synonymous with an absence of moral and philosophical vision. And then you used your outsider’s judgment of a situation about which you know nothing to bolster your cause. You fell into one of the worst tropes our society has to offer about disabled people: that disability is a physical and moral tragedy.

May I make a suggestion? When you’re fighting for social justice and general kumbaya, avoid the ableist language. Is that so hard?

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Amanda Baggs, the Pressure To Die, and the Case Against Assisted Suicide

Most people in the disability community know Amanda Baggs as a blogger, a disability rights activist, and the creator of the powerful video, In My Language. I first came to know Amanda in all those ways as well. Then she became a friend, and I found her to be one of the most ethical people I have ever known.

I’ve been pondering for days about how to write at length about what is happening to Amanda. Words have been failing me. All I’ve been able to feel is a deep sadness and a deep outrage that nearly take my breath away. But it’s time — not only because Amanda is a friend and a colleague, but also because her situation shows how easily vulnerable people are pressured to die by those who feel their lives are not worth living.

Amanda is autistic. She is also a wheelchair user and has a condition called gastroparesis (GP) — paralyzed stomach. Because of this condition, Amanda has had several bouts of aspiration pneumonia. The treatment for aspiration pneumonia is excruciating, and another bout could kill her. The only way to save her life is the insertion of a G-J tube through which she can both receive nutrients and vent air and bile from her body. Several doctors at the hospital in which Amanda is a patient suggested a G-J tube, and Amanda decided she wanted it. She has been quite clear about her desire to live.

A life-saving procedure to which a patient agrees ought to be the end of the story. But in the case of a woman with multiple disabilities, it hasn’t been. Amanda has had to fight for the insertion of the G-J tube in the midst of illness and exhaustion. In one especially ghastly encounter, she had to argue with a gastroentereologist who kept suggesting “alternatives” — when they both knew that the only alternative was death. In a post called The weirdness of being told that the death alternative is the one I should consider, Amanda writes:

Every doctor since I got here has been talking about feeding tubes. I discussed it with them and chose the g-j tube. In reality I chose it months ago. There’s been talk about feeding tubes since I was diagnosed with gastroparesis last fall and again when the diagnosis was confirmed this winter. This talk isn’t new or scary. I’m more comfortable with the prospect of a feeding tube than anyone else in the room, aside from being a little afraid of the pain early on after the operation.

…

What became really disturbing was the gastroenterologist’s attitude towards my treatment. He kept trying to find ways to persuade me that I didn’t want a feeding tube. He said I had to consider alternative options. My DPA pointed out that the current alternative option was death from pneumonia. The gastroenterologist confirmed that he knew that was the only current alternative. Then he went back to what a big scary decision a feeding tube was, and other things intended to dissuade me from what’s known both with gastroparesis and other neurological problems causing these problems, to be commonly the next course of action.I simply can’t continue aspirating like this, getting pneumonia this often is a very bad thing. I’ve had a number of close enough calls I’m not interested in getting any closer.

But apparently this guy, even after “the alternative is death” was spelled out, not only agreed to this, but still kept pushing “the alternative”. And he was not the only person who appeared to know my life was in danger yet kept asking me to reconsider getting the tube, they’ve tried all kinds of ways.

On what possible basis would a doctor discourage a patient from having a life-saving procedure when the patient clearly wants it — and when several other doctors had already suggested it? It makes no rational sense at all. The only way it could possibly make sense is if one started from the premise that Amanda’s life was not worth saving in the first place.

How can a life not be worth saving? Apparently, when it’s a disabled life.

I don’t consider that viewpoint a rational premise on which to base any decision. I think that anyone who believes that a disabled life isn’t worth saving is engaging in bigotry deep and wide, and that kind of bigotry is never rational. It is always based on fear and loathing, no matter how rationally the notion might be presented, and no matter what the educational credentials of the person presenting it.

But, thank God, Amanda’s life is being saved. After a great deal of work by her fierce DPA and numerous outraged phone calls from disability rights activists all over the country, the doctors finally assented to inserting the G-J tube. But the question of the very worth of Amanda’s life remained. After she had signed the consent forms, a pulmonologist asked her not once, but three times, whether she was “at peace” with her decision.

Now, I can understand asking someone whether they’re at peace with a decision to refuse treatment, even though it means death. It’s always a concern that people feel absolutely sure that they want to forego treatment, because death is an irreversible choice. But it makes no rational sense to ask a person who has vehemently expressed a desire to go on living whether she is at peace with the prospect of going on living. And yet, that’s what happened. As Amanda tells it in “Are you at peace with your decision?”:

Before I got my feeding tube. After I’d already signed an informed consent form. A pulmonologist came into my room with a gaggle of interns and residents behind him. People who were learning from him. People who looked up to him as a teacher and role model.He had seen my cat scan. He knew how many times I’ve had pneumonia recently. He knew it would keep happening if we didn’t find a way to stop it. He knew that pneumonia is a deadly disease and that my health was worsening with each infection. He knew how many doctors had tried to talk me out of choosing the feeding tube — choosing to live.

“Are you at peace with your decision?” Is a question I would expect to be asked repeatedly if I’d chosen to avoid treatment and go home and wait to get the infection that would kill me. Not a question that goes with choosing life. He asked me at least three times in a row.

I had a friend who came to visit from out of state, in the room with me at the time. She came because she heard I had pneumonia. Her father died of pneumonia. She was terrified for my life. She witnessed this conversation — easily, as she put it, the most genteel of the ways I’d been pressured to die.

There has been a great deal made lately of the so-called right to die — the right of terminally ill patients to obtain a lethal dose of medication in order to end their lives. Advocates for “death with dignity” believe that they can put enough safeguards in place to ensure that people are able to make a free and autonomous decision, protected from outside pressure at the hands of parties who do not have their best interests at heart.

Under our current system, the very notion of this kind of autonomy is a dangerous myth. There can be no free and autonomous decision to die with dignity when people who want to live with dignity are not encouraged to live — when the very idea that they can live with dignity is not even on the radar of the doctor who walks into the room.

Let’s face it: disabled people represent the failure of the medical profession to live up to the mythology our culture has built around it — that cures are right around the corner, that medical science is all powerful, that life can be made perfect and pain free, and that even death can be put off indefinitely. People with disabilities are an affront to a culture that idolizes the medical profession and assigns it all kinds of power it does not have. The myths by which we live fail abruptly in the presence of a person with disabilities, and doctors are no more immune from the power of those myths than anyone else.

What happens to people who don’t have the support that Amanda has? What happens to people who are sick, and in pain, and alone, and don’t have a fierce advocate? What happens to people who aren’t well known in the disability community? What happens to people who do not realize that they have worth, who do not realize that they have the right the right to live? What happens to people lying in hospital beds, uncared for, feeling that their lives means nothing because of all of the genteel and not-so-genteel ways in which that idea is communicated? How many people feel that they are simply a waste of space because they’re being pressured to choose the alternative of death?

In this kind of environment, no free choice is possible. And I think that the proponents of assisted suicide know that. I really do. In fact, I think that the very reason that people put assisted suicide on the table at all is that they know the kind of treatment in store for them if they become ill or disabled. It’s not really illness or disability they fear, because it’s entirely possible to live a very good life with illness and disability in it. What people fear most is being treated as though they have no dignity, as though they have no worth, as though their lives matter not at all. This is the deepest fear: to not matter. Even pain and death pale in the face of it.

I think that many people feel that they would rather die than to be treated as though they are worthless. And so they put forward legislation that will give them a way out. But they don’t realize that we can fight the idea that it’s better to be dead than ill or disabled — that we can react to it with outrage, and that we can create communities of support so that none of us ends up with our worst fears realized.

We have to. We can’t give up. We can’t give in to the idea that death is better than life. Because what is happening to Amanda Baggs should scare the hell out of all of us, and we need to take that fear and listen to what it’s telling us.

The reaction to fear can’t be surrender. Not when life is at stake.

References

Baggs, Amanda. “In My Language.” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JnylM1hI2jc. January 14, 2007. Accessed April 6, 2013.

youneedacat. “The weirdness of being told that the death alternative is the one I should consider.” http://youneedacat.tumblr.com/post/46816346769/the-weirdness-of-being-told-that-the-death-alternative. March 31, 2013. Accessed April 6, 2013.

youneedacat. “Are you at peace with your decision?” http://youneedacat.tumblr.com/post/47251303580/are-you-at-peace-with-your-decision. April 6, 2013. Accessed April 6, 2013.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

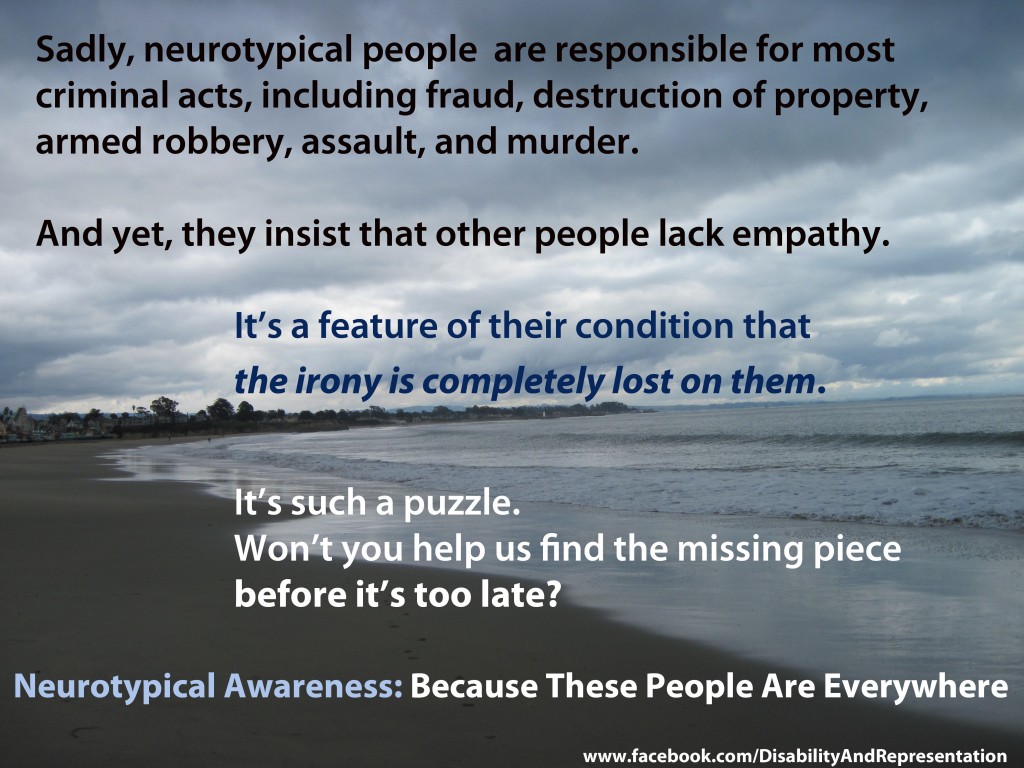

Neurotypical Awareness: Some Clarifications of Intent

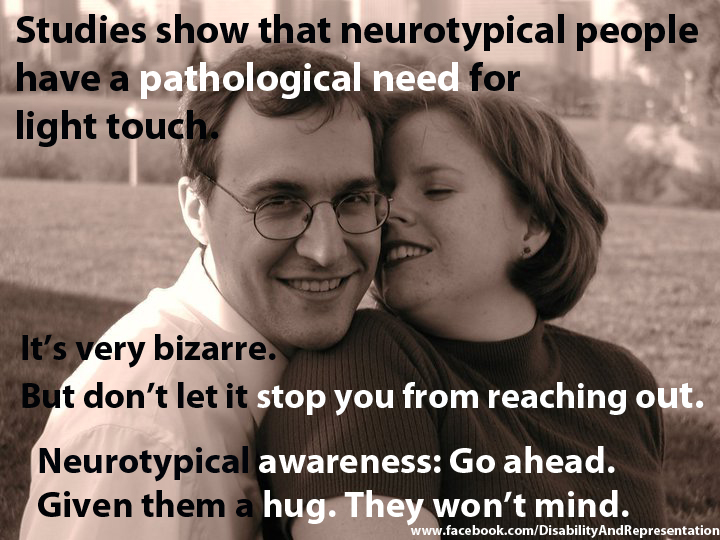

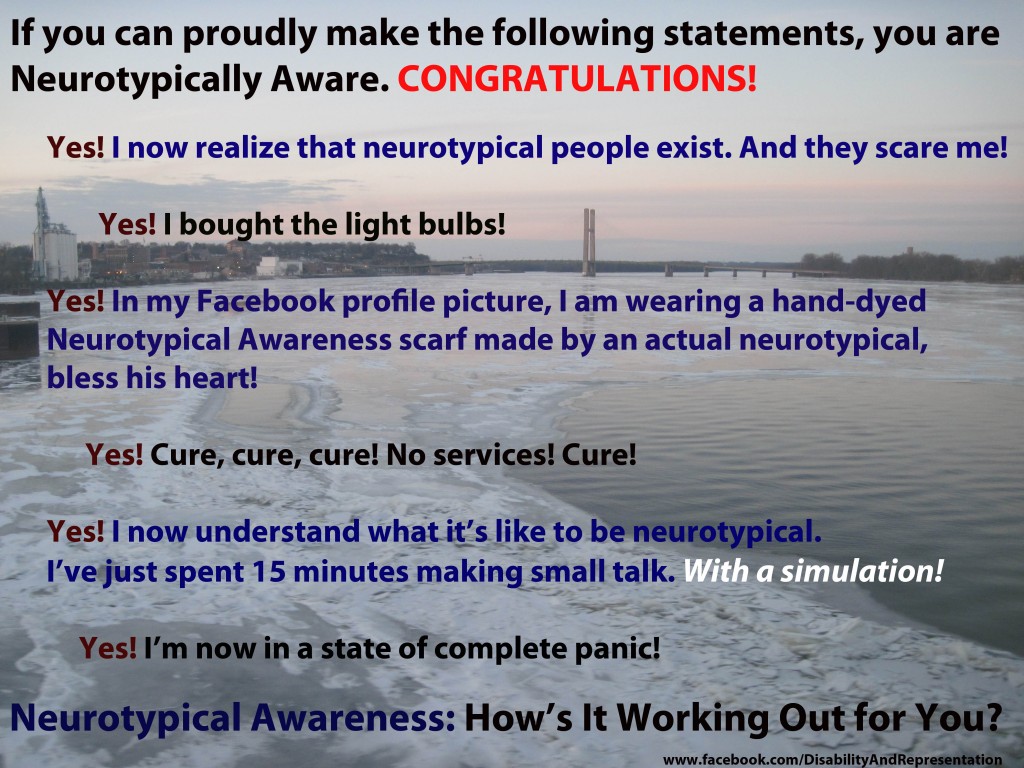

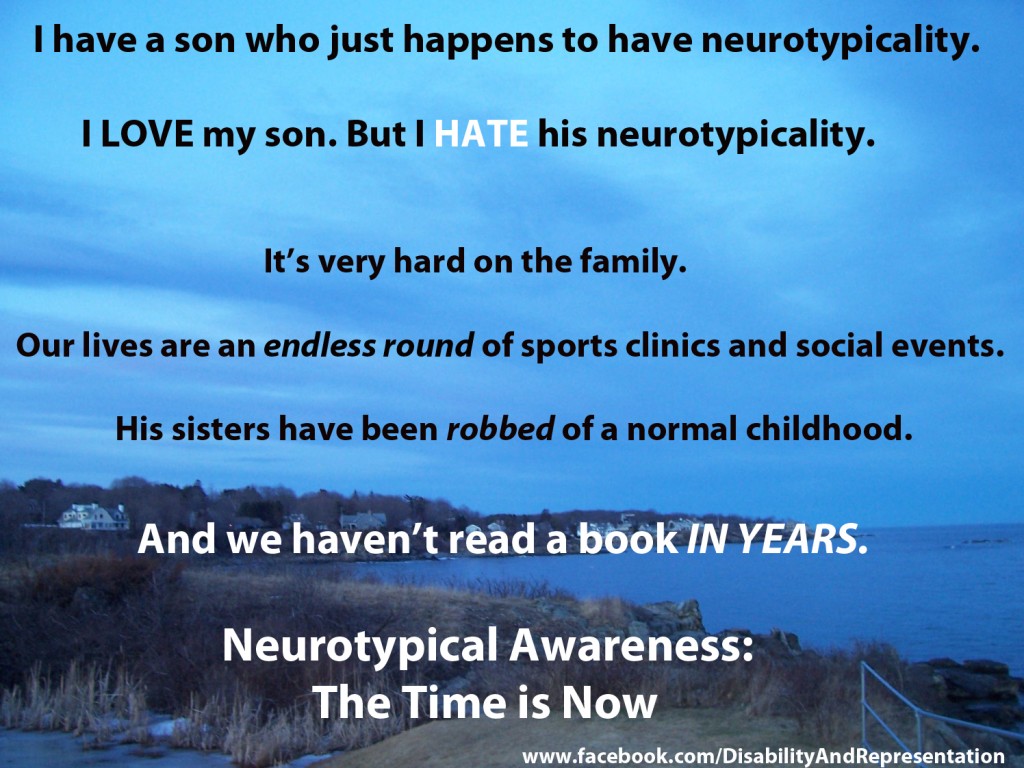

I’m really gratified by how many people have shared my Neurotypical Awareness memes and all the great comments that these memes — you should pardon the expression — have inspired. Based on some of the comments I’ve seen over the past week, though, I feel it necessary to clarify a few things for people who are unfamiliar with my work and approach.

The intent of the Neurotypical Awareness memes is not to parody individuals or their concerns. For instance, I’m not saying that raising an autistic kid is easy, and I’m not saying that being autistic is easy, and I’m not saying that people should be quiet about it. Physically, socially, economically, emotionally, and in many other ways, it can be very difficult — because of the nature of the condition and because of the obstacles that the world puts up. What I’m doing is parodying representations of autism — by professionals and organizations and media outlets — that constantly beat the drum about how autism is nothing but tragedy and grief and loss and deficit, or conversely, a grand opportunity for Special Inspirational Achievement and Overcoming the Odds.

I don’t think those extremes help us. And those are generally the extremes at which most mainstream autism representation works. The same is true for mainstream representations of most — if not all — disabilities.

It’s clear that a number of people feel uncomfortable about these memes. My feeling is that this discomfort is a good thing. If people are uncomfortable when reading them, then what I’m doing is effective. People should feel uncomfortable when the shoe is on the other foot and pejorative attitudes are directed at them or at those they care about. I want people to have the experience of how it feels for disabled people to deal with these kinds of messages day in and day out.

The problem, from my perspective, isn’t that people get offended. The problem is that people get offended and then don’t question why they’re offended and why I’d want them to feel that.

Several people have said that I’m just being negative. But that’s not me. I don’t do negative for the sake of negative, and I have no interest in paying back the non-disabled world for the way it treats us. I don’t think about life that way. My only interest is to shine a light on our cultural memes about disability and on their impact.

In other words, this isn’t therapy. It’s social commentary. And if it makes you uncomfortable, then I’m doing my job.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg