Privilege at Work in the Pharmacy Line

I had an interesting moment at CVS tonight.

I walked over to the store to pick up an epi-pen. (Yesterday morning, I had my first allergic reaction to a bee sting ever, so I’ve been working on getting an epi-pen all day.) To pick up a prescription at CVS, you have to stand in a line by the pick-up counter at the back of the store. Tonight, the line consisted of an elderly white man in front of me who was holding a cane, and a younger African-American man behind me. I was standing between them with my cane as well. The elderly man in front of me was easily 80 years old and fairly unsteady on his feet. He was leaning against the shelves and looking quite tired.

As we were standing there, a young and apparently able-bodied white dude came over and asked the elderly man, “Are you in line?”

He said “Yes, I am. I’m picking up a prescription.” The young man looked at me for confirmation, and I gave him an emphatic nod — as if to say, “Why do you think we’re standing in line here? For the view at the back of the pharmacy?”

And what did he do? He cut in front of the line. He went right up to the pick-up counter for his prescription. I kid you not. I could hardly believe my eyes. Thanks be to God the woman behind the counter told him he’d have to wait his turn. When he realized that he had to stand behind the rest of us, he left.

These kinds of microaggressions are so disturbing to me. A line is one of the few democratized spaces left. You get in line and you wait your turn. And for the love of God, you do not cut in front of an elderly man who is unsteady on his feet and clearly laboring to stay standing. If I hadn’t been so tired, I’d have said, “Nice try throwing around your privilege, pal.”

I just don’t understand that level of chutzpah. I don’t think I ever will.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Guest Post: No Apologies

Following is a guest post by my husband, Bob Rottenberg, about his experience of going through airport security with disabilities. Bob uses a knee brace and has some age-related hearing loss, with tinnitus in his right ear. He travels frequently between the coasts.

No Apologies

I’m traveling a lot these days, mostly flying to and from California to spend time with my very frail and very old father in New York City. On the average, I make the round trip once a month. This means going through airport security twice (coming and going) in the span of a week or so.

I’m almost 69, in good physical health overall, but there are two things that slow me down.

One is my hearing, which is still OK, but my right ear isn’t what it used to be, so I’m increasingly affected by background noise. The other is my right knee, which is ready to have some torn cartilage removed. As a result, when I travel I wear a fairly substantial brace on that knee. A brace that always sets off the body scanner alarms.

I’ve become both resigned to and accepting of the pat-down by the TSA screeners – knowing that the only thing they’ll find is a knee brace, which is not a problem for them.

Because I know that I have to go through this process, I try very hard to get to the airport with plenty of time to spare. This allows me to be as relaxed as possible in a very stressful environment. And it allows me to cooperate with the screeners, and let them know what’s going on for me.

Today, because the New York airport didn’t have the latest screening technology, I had to undergo a “full-body” pat-down. The agent started explaining what he was going to do, asking if I understood and assented. The problem was, even though I knew what he was going to do, I couldn’t really understand what he was saying, and didn’t want to simply nod in agreement. Part of it was my hearing, which is always compromised in a noisy environment. The other was the agent’s speech, which was both unclear, due to his accent, and coming at me at a very rapid pace. So I kept asking him to repeat what he had said, because I literally could not make sense of his words, and I didn’t want to get anything wrong, and risk setting off more alarm bells and having to sit on the Group W bench with the other hardened criminals – and, of course, risk missing my flight home.

At that point, a female agent came along and, perhaps realizing that I wasn’t understanding the first agent’s attempts at the King’s English, repeated everything he had said, but more clearly. The exam proceeded, took all of one minute, and I was cleared for takeoff.

So what did I learn from this? That it’s important for me to not apologize about my “condition;” that’s it’s OK to for me to slow things down, to make sure I understand everything that’s being asked of me, and to then do everything I can to make the job of the agents go more smoothly – all so that my day can proceed more smoothly.

And today, this worked. I refused to apologize for my condition – for my less-than-adequate hearing, and for my knee-in-need-of-surgery – but I was completely willing to let them know what I needed, in as non-confrontational manner as possible. This is who I am right now, and I accept my condition fully. But I also realized that I did not want to make my condition a “problem” for the agents. This is why I insisted on taking the small amount of extra time to make sure I heard and understood what their needs were. I’ve seen too many instances where the lack of clarity leads to unfortunate outcomes.

Not feeling rushed certainly helps me to take full responsibility for myself in these moments. I can imagine how I would feel if, under pressure to make that flight in the next ten minutes, I had to do combat with agents whose words I could not clearly understand. I take the approach that they are there to help me get to my destination safely. And my responsibility to them is to be as clear as I can about my own needs, so that we can both get on with our day in as pleasant a way as possible.

And this is what I learned: Just as they shouldn’t have to apologize for simply doing their jobs, I shouldn’t have to apologize for being who I am.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Why So Many Fail to Understand Systemic Oppression

I was recently in a discussion about the ways in which people of color are disproportionately targeted by the police (think: stop-and-frisk, among other rights violations), disproportionately incarcerated, and disproportionately imprisoned for long stretches. As is often the case in these kinds of discussions, someone came blundering in with a “solution” — the “solution” being that people of color just need to be compliant with police officers and not do anything at all that could possibly be construed as suspicious or alarming. In other words, people of color simply had to act “normal” and all would be well.

I kept reading those words over and over, because I found them so shocking. It wasn’t just that the ideas were wrong — that they evinced an ignorance of racism and an idealized sense of control. It’s that they were based on an outlook that I once believed was grounded in fact: that society is “just” and that all I had to do to be safe was to do everything “right.”

That was a lifetime ago. At some point, I realized that there was no way to do it “right” because, in the eyes of the society in which I live, I am already seen as “wrong.” This assumption of wrongness is why marginalized people get the attention of the police, not to mention other authority figures, for driving while black, for walking while trans, for standing while disabled. We’re already considered “wrong” in the first place.

Some people’s bodies are themselves considered provoking. Not our intentions. Not our attitudes. Not our actions. OUR BODIES. To understand this very basic fact goes against the whole notion that the society one lives in is just — that the good are rewarded and that the guilty are punished. It’s deeply terrifying to realize how truly irrational people are when it comes to the arbitrary meanings they place on human bodies. It means that entire systems are based on completely arbitrary and irrational standards. It goes against the whole Western notion that humans are rational and enlightened beings.

It’s a very hard thing to wrap your mind around until it comes your way. And even when it does come your way, it’s still something that is difficult to face. This is one of the reasons that even people inside marginalized groups can fail to grasp the systemic injustices directed against their bodies. Or if they do grasp it, they can fail to understand the irrationality of the hatred directed toward other people’s bodies. So you find gay and lesbian people who are racist and transphobic, and you find people of color who are homophobic and ableist, and you find transgender people who are ageist and fatphobic, and you find disabled people who are misogynist and classist. Depending on who you talk to, you’ll find a multitude of permutations of all of these bigotries, including the horrifying specter of internalized hatred against one’s own body.

To realize that these valuations are simply arbitrary — that there is no good reason at all to suspect a body just for being a body — means to recognize that we are all at risk. Stigma is a moveable feast. It is mercilessly easy to move from a privileged category to a stigmatized category. Just ask anyone who has ever been diagnosed with a disability after living with the privileges of able-bodiedness, or anyone who has ever become fat after being thin, or anyone who has become old after a lifetime of looking youthful. The whole notion that the society is constructed along rational lines comes crashing down. And then you have to reconstruct your sense of how it works, piece by piece.

You’ll find other people who have woken up and found a new way of seeing. But you’ll never really believe again that the world you live in is just.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Evading Responsibility by Making Science the Solution

I have been reading, with great interest, Susan Wendell’s The Rejected Body. I have been particularly interested in her analysis of our cultural “myth of control” — the notion that we can control our bodies and protect them indefinitely from illness, disability, and death — and the ways in which disabled people become stigmatized for being an affront to this myth (Wendell 1996, 93-94). Wendell writes that the emphasis in Western culture on curing disability, and all of the millions of dollars spent on cures that never come, is a manifestation of our discomfort with the fact that what happens to our bodies is largely out of our control (Wendell 1996, 94). Our bodies age, they break, they do things we don’t want them to, they don’t do things we do want them to, and ultimately, they fall apart and die.

Our faith in science and medicine to exercise control over disability and death means that resources don’t go to the things that we can control for disabled people. I agree with Wendell that medical science should continue to act in the service of easing suffering, healing illness, and saving lives, but the emphasis on control through science is so extreme that we neglect all the ways in which we can make life better for people who are living, right here and right now, with disability (Wendell 1996, 110-111). We spend an inordinate amount of time and money waging war on disability and death, and very little time and money on things that we actually do have some power over — such as whether buildings are accessible, employment is available, housing is affordable, medical care is within reach, and people generally have access to all of the things that make life more than mere survival.

The myth that we can control our bodies against difficulty, illness, injury, aging, and death is simply a blanket denial of physical reality, but the more I look, the more I see this myth all around me. I see it when people assert that you can protect yourself against rape by how you dress. I see it when people hawk the latest weight-loss program, as though within every woman is a sleek supermodel just waiting to be born, and as though it were a mark of shame to be anything else. I see it in advertisements for products that promise to reverse the visible signs of aging, as though aging were an insult to human dignity. I see it whenever I read an obituary about someone having waged a “courageous battle” against whatever they died from, as though they have gone down in defeat, rather than simply surrendered to an entirely natural — and inevitable — process.

Recently, while all of these issues were knocking around in my brain, I happened across the article David Frum on How We Need to Learn to Say No to the Elderly. Please be warned: the article is very painful reading. It is full of blatant ageism, beginning with the entirely inaccurate assertion that elderly people are the worst drivers in America. In point of fact, according to a report from the census bureau for 2009 (the latest date for which such statistics are available), the worst drivers are those between 25 and 34 years of age, with drivers over 65 accounting for the fewest numbers of accidents (just over 8%). And then there’s a lovely graphic showing the proverbial little old lady in the huge automobile about to drive into a terrified 30-something young man. The caption credits Darren Braun for the photo illustration; all I can say is, How proud he must be! The rest of the article is a scapegoating, dividing-and-conquering mess. It blames elderly people on Medicare and Social Security for bankrupting the young and causing the economic woes afflicting the US; in fact, the subhead reads, in part, “If we don’t push back, they’ll steal our benefits and bankrupt the country.” In this, it reads in a manner reminiscent of the tabloid stories in the UK that blame disabled people for the recession (Briant et al. 2010, 9).

So the article was a tough go, but what I found most troubling were some of the responses. I try to stay away from reading comments to most news articles, lest I despair of humanity altogether, but I was anxious to see whether anyone had called out Frum’s absurdities. Fortunately, a number of people had, but a few had chimed in with absurdities of their own. One comment, in particular, caught my eye as an interesting fantasy of what to do about the “problem” of elderly people bankrupting the economy with their lavish Social Security checks. It read, in part:

Simple: fix aging, as in lets use the now rapidly developing sciences of biotech and nanotechnologies to reverse aging….Aubrey de Grey, founder of the Mpize and the SENS foundations (now with the SENS foundation) estimates we need just 1 billion, spent over a 10 year period, to eliminate the day to day damage of aging in a mouse model, then people in the next decade).

It’s not the first time I’ve read someone excitedly going on about science putting a stop to the aging process, and I’m sure it won’t be the last. Every time I see it, I’m caught between wanting to laugh uproariously and feeling myself holding back tears of desperation. On the uproarious side, I find it hilarious that anyone would believe that science could stop the aging process. I mean, the implication is that we’d be young forever and… then what? Never die? How would that work exactly? Once science stops the aging process, would it also stop all other breakdowns in the body? And if that were the case, and no one dies anymore, exactly how are we supposed to all crowd together on this tiny little planet? I realize that, in this culture, death is a bitter pill to swallow for most people, but honestly, it’s the cost of doing business on Mother Earth. We each have our time, and then we leave so that others can have their moment as well. If no one died, the planet would become so crowded that we’d destroy one another.

But mostly, when I read these kinds of comments, I feel a combination of puzzlement and exasperation at the assumptions that underlie them. First of all, there is the assumption that aging is a problem. Personally, I don’t have a problem with my body aging (although I could do without the stigma that attaches). I mean, what’s the problem with aging, except that it’s a sign that you can’t live in denial of death forever? Then, there is the assumption that the problem is in the body, rather than in the world at at large — a common assumption in a society enmeshed in the medical model. Finally, there is the assumption that we need to fix the body instead of the way we structure society and allocate resources. This assumption is the most troubling of all. The idea of putting more faith in science than in the moral conscience and behavior of other people really frightens me. Have we really lost that much faith in the power of human beings to work collectively, to do the right thing, and to make positive political change? Are we really turning our moral obligations over to science, fleeing our responsibilities of care and compassion for one another?

We create a world of suffering: young people can’t find jobs, middle-aged people lose their homes, elderly and disabled people end up isolated in nursing homes or on the street. And then we say, in response to the suffering we’ve created, that if we could only change the bodies of elderly and disabled people, society would work swimmingly. Somehow, the suffering we’ve created outside the body begins to adhere in the body, and the conversation turns to “fixing” the body — ending disability, aging, and ultimately, death. I worry about a world with such zealous faith in science to solve problems that require moral will and political action. I worry because service to one another is the highest calling in human life, and while science can be put in the service of that calling, it can never be a substitute for it.

References

Briant, E., N. Watson, and G. Philo. Bad News for Disabled People: How the Newspapers Are Reporting Disability. Glasgow, UK: Strathclyde Centre for Disability Research and Glasgow Media Unit, University of Glasgow, 2010.

The Daily Beast. “David Frum on How We Need to Learn to Say No to the Elderly.” http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2012/06/24/david-frum-on-how-we-need-to-learn-to-say-no-to-the-elderly.html. June 25, 2012. Accessed July 4, 2012.

The United Status Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s1114.pdf. Accessed July 4, 2012.

Wendell, Susan. The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability. New York, NY: Routledge, 1996.

© 2012 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Ableism and Ageism in One Tidy Little Package

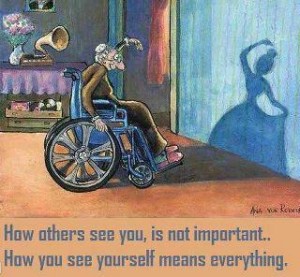

Source: Facebook

I have only two positive things to say about this graphic:

a) I’m sure the person who put it together had the best of intentions.

b) I love the Victrola in the background.

Now for my critique. Let’s start with the text:

How others see you, is not important.

How you see yourself means everything.

The text is meant to inspire and support us in laying claim to our own self-representations. Okay. Fair enough. It’s abundantly true that my own sense of myself should be more important than other people’s ideas about me. People have told me such things from the time I was a small, sensitive child, overwhelmingly in tune with what people thought about me. What they didn’t tell me was how much my sense of myself and other people’s sense of my self were intertwined. I’ve since realized, of course, that most of us get our ideas about ourselves as a result of how others look at us, how they treat us, and whether they respect and value us. If you’ve been victimized, or bullied, or misrepresented, or otherwise had your sense of yourself messed with, it’s necessary to reclaim your sense of who you are, but it generally doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It takes the support of other people giving you a relatively undistorted mirror in which to see yourself. The need for such a mirror is why I read so widely about the experiences of other disabled people, why I read every piece of disability theory I can get my hands on, and why I have so many disabled friends. If I didn’t, I might actually believe the things that people say about disability.

Which brings me to the question of what people say about disability, and how the graphic uses disability and aging for the purposes of inspiration. The elderly woman in the wheelchair represents the first part of the text: How others see you. What do they see? Literally speaking, they see an elderly woman in a wheelchair. Of course, no one except a Zen master sees anything literally without attaching to it some value or interpretation, so there is a symbolic meaning attached to being elderly and disabled that makes being elderly and disabled a bad thing. Why do I draw the conclusion that a negative meaning has been attached? Because the first part of the text, How others see you, is placed in contrast with the second part of the text, which talks about what’s really important: How you see yourself. The message is that if people see you in a bad light, what’s most important is that you see yourself in a good light. Apparently, to be old and disabled is to be seen in a bad light.

What does one do in such a predicament? Why, one just imagines oneself as a young, typically able-bodied dancer with an hourglass figure — perhaps a former self that no longer exists, perhaps a fantasized self that never existed at all. Apparently, this kind of imagining is what is means to see oneself in a good light. The message is that young able-bodied dancers with hourglass figures are worthy of esteem, but elderly disabled people in wheelchairs are… not. If you are old and disabled, then, and you want to have healthy self-esteem, you need to imagine that you are someone else. I’m not clear on how one does such a thing without losing touch with the reality of one’s own existence, or without becoming so psychically estranged from oneself as to create an unhealthy amount of stress and self-hatred. Perhaps someone can explain that to me. My attempts at pretending to be someone else have generally been met with anxiety and ill health.

At any rate, it’s clear from the graphic that the association of being old and disabled with low self-esteem is simply a given. It is never questioned. It is assumed that there is something essential about aging and disability that is in itself degrading. No attention is paid to the fact that feelings of degradation have their roots in a cultural rejection and abasement of elderly and disabled people. As Susan Wendell points out, we live in a culture with a nearly pathological desire for control, which causes most people to reject people who show signs of aging and disability:

Disability tends to be associated with tragic loss, weakness, passivity, dependency, helplessness, shame, and global incompetence. In the societies where Western science and medicine are powerful culturally, and where their promise to control nature is still widely believed, people with disabilities are constant reminders of the failures of that promise, and of the inability of science and medicine to protect everyone from illness, disability, and death. They are ‘the Others’ that science would like to forget (Wendell 1996, 63).

The symbolic meanings associated with aging and disability — loss, weakness, dependence, and death — provide both an incentive and a justification for rejecting elderly and disabled people. These meanings spare the able-bodied the responsibility for acknowledging the vulnerability of their own bodies, allow them to deny that they could become disabled at any time, and provide a way for them to distance themselves from the inevitability of death (Wendell 1996, 60). Once these meanings are in place, the burden falls on the shoulders on elderly and disabled people to solve the problem of becoming devalued and unwanted. This state of affairs is apparent in the graphic, as the onus is on the elderly woman to imagine herself to be someone else, rather than on other people to see her — and to treat her — as someone who is beautiful, valuable, and respected.

Forcing minority people to shoulder this burden is a process deeply entrenched in our culture. The aim of many professionals is to get us to adjust to our lot in life by changing our own attitudes and perspectives, rather than by fighting to change the attitudes and perspectives in the world at large that cause us so much grief and pain. When my disabilities became apparent in mid-life, I went through a great deal of sadness and frustration over both my physical difficulties and my social exclusion. The ways in which our society treats disabled people were weighing heavily on me, but my therapist insisted that I simply needed to find better coping mechanisms. At one session, I constantly challenged him with a version of “But why is it solely my responsibility to handle exclusion, and not the responsibility of the people who engage in it?” In response, he simply repeated the phrase “It’s your problem,” as though I were missing a necessary piece of wisdom that only repetition would make clear. Needless to say, that was our last appointment.

Of course, I am not at all opposed to disabled people developing coping mechanisms. That’s a necessity. What I oppose is ignoring the conditions in the world at large that force us to spend so much time and energy developing coping mechanisms in the first place. And I resist the idea that imagining oneself to be a member of the unstigmatized majority is a healthy way to deal with stigma. Rather than fantasizing about being someone else, we ought simply to demand that people respect us for who we are.

References

Facebook. http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10150887120344632&set=p.10150887120344632&type=1&theater. Accessed June 21, 2012.

Wendell, Susan. The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability. New York, NY: Routledge, 1996.

© 2012 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg