ZOMG! Look! A Disabled Person Does Something!

On October 23, CBS News in New York ran a story about an autistic high school football player who kicked a game-winning field goal. The event was, according to the headline, “a moment for the ages.” I am not exaggerating:

Source: CBS New York

I’m going to parse the article a little bit at a time. It’s a combination of some great statements by the young man and his parents, and some absolutely atrocious inspiring-crip/perpetual-special-child material. It’s really a shame that the framing is so bad, because the statements from the player himself and the people involved in his life are really quite wonderful.

The article begins:

A high school student with autism becomes a hero on the football field. Sounds like a good movie doesn’t it? Well, it’s a true story.

So, right away, we’re in supercrip mode. The guy is a hero. And, at the same time, we’re led to believe that it is so absolutely unfathomable that a disabled guy should be a hero that it’s just like fiction. And since it actually happened in real life, we should all sit down before we faint.

It’s also kind of interesting that one kind of media is calling upon a different kind of media in order to frame the rather mundane occurrence of a football player kicking a winning field goal. We’re being asked to see the story not only from the perspective of a news report, but also as a kind of theatre. So we have two levels of interpretation layered over the fact that a young man kicked a football through a pair of uprights.

What makes the lens even more distorted is that, despite the frame of a “good movie,” I can’t think of a Hollywood movie in which a disabled person becomes an athletic hero. I can think of some in which the disabled person dies (Hello Million Dollar Baby), or ends up running madly around the soccer field with his kid on his shoulders (Hello I Am Sam), or draws with his foot (Hello My Left Foot), but I’m drawing a blank on a film with this theme. Maybe there is one, but the fact that it isn’t springing to mind troubles me, because the lens is about something that eludes my grasp. I keep thinking, “Well, of course there is one… Isn’t there?”

The score was tied with just 21 seconds left on the clock Friday night. Out trotted Brick High School’s Anthony Starego, an 18-year-old kicker who’s used to facing adversity.

Uh oh. There’s that adversity word. Always with disability, there’s that adversity word, just to make the mundane appear extraordinary. Do people not understand that life is a difficult thing for most human beings, and yet, we somehow manage to do things?

Starego was orphaned at the age of 3 and then grew up with a long list of developmental issues. So when he jogged out on the field to attempt a game-winning field goal against favored Toms River North, one couldn’t blame him if he didn’t feel overwhelmed by the moment.

The young man has certainly faced his share of hardship in losing his parents. There is no denying that. But that’s not what the word adversity is really about here. It’s about his autism. It’s about his “long list of developmental issues.” It’s about his body and what a burden it appears to be for the person narrating his story. If he had simply been orphaned, it wouldn’t be a story. His disability is the focus.

What happened next was something usually reserved for Hollywood.

What? Disabled people don’t accomplish things in real life? Are we that boring?

And let’s be clear on what we’re talking about there. The young man kicked a field goal. A field goal. In a high school football game. Don’t get me wrong. It’s really fantastic that he won the game for his team. I’m completely excited for him. I’m just trying to understand why this is some sort of heroic and inspiring moral tale.

Oh, that’s right. The subtext is “A disabled person accomplished something, and we’re all shocked and amazed, because we all thought it was impossible, and now we have to make up a story about how it was nearly impossible.”

Okay. I’m getting it now.

He split the uprights and the place went crazy. But there was nothing ordinary about that kick. It was a lifetime in the making, CBS 2′s Otis Livingston reported Tuesday.

Wait. If you’re a high school football player, isn’t just about anything you do on the field “a lifetime in the making”? How is Anthony’s lifetime of working on his game any different from anyone else’s lifetime on that field? I’m assuming they all started out throwing a football in their backyards or at the park or in the street.

“As soon as the officials went like this, I was a blubbering idiot,” father Ray Starego said, demonstrating the hand movement for a successful field goal.

“I was just crying, but I wasn’t going to stop watching him because he was just jumping for joy. It really was unbelievable,” added Reylene Starego, Anthony’s mother.

Now, I love this part. I seriously do. In my book, the only people who get to cry and kvell and act like kicking a field goal is the greatest moment in the history of humankind are the parents. That’s what parents do. We get emotional. We get over-the-top emotional. About a game. Because we want our kids to be happy, and we want them to accomplish everything they set out to do, and the last thing we want is for them to come off the field in tears of disappointment.

I went nuts when my kid played goalie for the high school varsity soccer team. I got emotional. Every single time someone came near the goal, my heart was in my throat. Every single time my kid blocked a shot, I was beside myself with joy, relief, and excitement. All that stuff is in the job description of being a parent, and Anthony’s parents are clearly quite good at the job. More power to them.

If being the hero Friday night put Starego at the top of the mountain, his entire life has been an uphill battle getting there.

“When he came to us, he had been through 11 foster homes and he had had some difficulties. He had about six words to his vocabulary,” Reylene Starego said.

“He had kidney reflux; he had an asthmatic condition. Basically, it was a special needs adoption that we had gone through,” Ray Starego added.

The guy has gone through a lot, obviously. I wonder, however, why the young man’s medical issues are germane here and available for public view. Did the reporter really have to mention them? Aren’t they Anthony’s business?

Symptoms of autism include children performing repeated body movements. They often experience unusual distress when routines are changed, but those are the same traits that make Anthony a successful kicker.

Notice that we’re talking about an 18-year-old young man and his repetitive movements and love of routine, but the text refers to “children.” We’ve now gone from supercrip mode to infantilization mode. Funny how that works.

“Fifty times a day, that’s all he does. Just three steps back, one over and he hits the ball. That’s what he knows and that’s what he did,” coach Kurt Weiboldt said.

Anthony Starego agreed. As far as he’s concerned, practice makes perfect.

“I do the same thing over and over again. It helps me a lot, and I’m having the best day of my life,” he said.

I really love what Anthony is saying here. It shows the way autistic hyper-focus and perseveration can be assets in adulthood. And he’s clearly proud of his intense focus. Awesome stuff. I wish the story had stayed closer to Anthony’s perspective, because that’s the frame that would have been most interesting.

Children with autism also have trouble with social interactions, so making friends isn’t easy, but the football field is different. It’s a safe haven.

And now we’re back to “children with autism.” Apparently, the writer does not have Anthony’s intensity of focus. If he did, he would notice that Anthony is not a child, but a young man. The fact that the writer frames Anthony’s statements with infantilizing terms takes a lot of power away from Anthony’s perspective. It’s as though we keep switching frames, from seeing him as a child being spoken for, to seeing him as an adult describing his own process, to seeing him as a child being spoken for again. It’s as though his adult status is just too much for the writer to keep in focus.

“[Anthony is] just the man. He’s always happy, always puts a smile on your face,” Brick High quarterback Brendan Darcy said.

Oh, dear. Now, not only is Anthony a supercrip and a child, but he’s also special. I highly doubt that the quarterback would have said about any of his other teammates that they always put a smile on his face. It’s just not what high school football players tend to say about one another. But it’s just so inspiring to be on a team with a disabled guy, you know?

Do people really listen themselves when they refer to others as “always happy”? How is it possible for someone to always be happy? Or does his teammate just mean that Anthony isn’t scary, the way he thought an autistic guy would be? Or maybe he’s just surprised that an autistic guy is excited to play the game, instead of moping around feeling really crappy because he’s autistic.

Anthony said he doesn’t think of himself as being different than his teammates. He said he just has a job to do.

“I feel like I’m happy and calm and enjoying myself when I kick. [It’s] the time of my life,” he said.

You go, Anthony!

The Green Dragons’ only two wins of the season have come since Anthony became the kicker. He’s perfect on kicks, including that game winner. Their next game is this Friday against Lacey High School.

Here at the end of the piece, I feel almost let down. I know I shouldn’t. Anthony has a perfect record, and that’s very cool. But what I’m feeling is that this story should never have been about Anthony kicking a field goal. That’s not the real story. The real story is that after going through 11 foster homes, the young man got adopted by supportive people and didn’t end up in an institution, and now he gets to play football. Now that’s a story.

But that’s not a football story. That’s a “let’s do something about all the others who don’t have supportive families” story. And once you start thinking of all of those people who will never have Anthony’s opportunities, you don’t feel too inspired. You feel downright pissed off and depressed.

And we can’t have that.

References

CBS New York. “Autistic Player Has Moment For The Ages, Kicks Game-Winning Field Goal.” http://newyork.cbslocal.com/2012/10/23/autistic-high-school-football-player-has-moment-for-the-ages-kicks-game-winning-field-goal/. October 23, 2012. Accessed November 1, 2012.

© 2012 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Ableism and Ageism in One Tidy Little Package

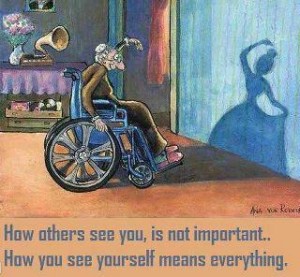

Source: Facebook

I have only two positive things to say about this graphic:

a) I’m sure the person who put it together had the best of intentions.

b) I love the Victrola in the background.

Now for my critique. Let’s start with the text:

How others see you, is not important.

How you see yourself means everything.

The text is meant to inspire and support us in laying claim to our own self-representations. Okay. Fair enough. It’s abundantly true that my own sense of myself should be more important than other people’s ideas about me. People have told me such things from the time I was a small, sensitive child, overwhelmingly in tune with what people thought about me. What they didn’t tell me was how much my sense of myself and other people’s sense of my self were intertwined. I’ve since realized, of course, that most of us get our ideas about ourselves as a result of how others look at us, how they treat us, and whether they respect and value us. If you’ve been victimized, or bullied, or misrepresented, or otherwise had your sense of yourself messed with, it’s necessary to reclaim your sense of who you are, but it generally doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It takes the support of other people giving you a relatively undistorted mirror in which to see yourself. The need for such a mirror is why I read so widely about the experiences of other disabled people, why I read every piece of disability theory I can get my hands on, and why I have so many disabled friends. If I didn’t, I might actually believe the things that people say about disability.

Which brings me to the question of what people say about disability, and how the graphic uses disability and aging for the purposes of inspiration. The elderly woman in the wheelchair represents the first part of the text: How others see you. What do they see? Literally speaking, they see an elderly woman in a wheelchair. Of course, no one except a Zen master sees anything literally without attaching to it some value or interpretation, so there is a symbolic meaning attached to being elderly and disabled that makes being elderly and disabled a bad thing. Why do I draw the conclusion that a negative meaning has been attached? Because the first part of the text, How others see you, is placed in contrast with the second part of the text, which talks about what’s really important: How you see yourself. The message is that if people see you in a bad light, what’s most important is that you see yourself in a good light. Apparently, to be old and disabled is to be seen in a bad light.

What does one do in such a predicament? Why, one just imagines oneself as a young, typically able-bodied dancer with an hourglass figure — perhaps a former self that no longer exists, perhaps a fantasized self that never existed at all. Apparently, this kind of imagining is what is means to see oneself in a good light. The message is that young able-bodied dancers with hourglass figures are worthy of esteem, but elderly disabled people in wheelchairs are… not. If you are old and disabled, then, and you want to have healthy self-esteem, you need to imagine that you are someone else. I’m not clear on how one does such a thing without losing touch with the reality of one’s own existence, or without becoming so psychically estranged from oneself as to create an unhealthy amount of stress and self-hatred. Perhaps someone can explain that to me. My attempts at pretending to be someone else have generally been met with anxiety and ill health.

At any rate, it’s clear from the graphic that the association of being old and disabled with low self-esteem is simply a given. It is never questioned. It is assumed that there is something essential about aging and disability that is in itself degrading. No attention is paid to the fact that feelings of degradation have their roots in a cultural rejection and abasement of elderly and disabled people. As Susan Wendell points out, we live in a culture with a nearly pathological desire for control, which causes most people to reject people who show signs of aging and disability:

Disability tends to be associated with tragic loss, weakness, passivity, dependency, helplessness, shame, and global incompetence. In the societies where Western science and medicine are powerful culturally, and where their promise to control nature is still widely believed, people with disabilities are constant reminders of the failures of that promise, and of the inability of science and medicine to protect everyone from illness, disability, and death. They are ‘the Others’ that science would like to forget (Wendell 1996, 63).

The symbolic meanings associated with aging and disability — loss, weakness, dependence, and death — provide both an incentive and a justification for rejecting elderly and disabled people. These meanings spare the able-bodied the responsibility for acknowledging the vulnerability of their own bodies, allow them to deny that they could become disabled at any time, and provide a way for them to distance themselves from the inevitability of death (Wendell 1996, 60). Once these meanings are in place, the burden falls on the shoulders on elderly and disabled people to solve the problem of becoming devalued and unwanted. This state of affairs is apparent in the graphic, as the onus is on the elderly woman to imagine herself to be someone else, rather than on other people to see her — and to treat her — as someone who is beautiful, valuable, and respected.

Forcing minority people to shoulder this burden is a process deeply entrenched in our culture. The aim of many professionals is to get us to adjust to our lot in life by changing our own attitudes and perspectives, rather than by fighting to change the attitudes and perspectives in the world at large that cause us so much grief and pain. When my disabilities became apparent in mid-life, I went through a great deal of sadness and frustration over both my physical difficulties and my social exclusion. The ways in which our society treats disabled people were weighing heavily on me, but my therapist insisted that I simply needed to find better coping mechanisms. At one session, I constantly challenged him with a version of “But why is it solely my responsibility to handle exclusion, and not the responsibility of the people who engage in it?” In response, he simply repeated the phrase “It’s your problem,” as though I were missing a necessary piece of wisdom that only repetition would make clear. Needless to say, that was our last appointment.

Of course, I am not at all opposed to disabled people developing coping mechanisms. That’s a necessity. What I oppose is ignoring the conditions in the world at large that force us to spend so much time and energy developing coping mechanisms in the first place. And I resist the idea that imagining oneself to be a member of the unstigmatized majority is a healthy way to deal with stigma. Rather than fantasizing about being someone else, we ought simply to demand that people respect us for who we are.

References

Facebook. http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10150887120344632&set=p.10150887120344632&type=1&theater. Accessed June 21, 2012.

Wendell, Susan. The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability. New York, NY: Routledge, 1996.

© 2012 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

When Inspiration Porn is Counter-Inspirational

Source: QuotesBuddy.com

This has to be the most confusing piece of inspiration porn I have ever seen.

Let’s start with the text: “The only disability in life is a bad attitude.”

Oh really?

Never mind that there are actual physical conditions that people have — some of them painful, many of them fatiguing, all of them quite undeniably real. Never mind that there are actual architectural and social barriers that render such conditions disabling. And never mind that all of these barriers result in massive unemployment, poverty, isolation, and exclusion.

Because all you have to do is adjust your attitude and all of these conditions and barriers will disappear. You live in a third-floor walk-up without an elevator? Turn that frown upside down, and your wheelchair will magically bring you down the stairs and out the door! Having difficulty finding work? Adopt a sunny disposition and no one will discriminate against you. Feeling socially isolated because other people shun you? Adopt a can-do attitude and you’ll have friends galore! Living in poverty? Cheer up, and you’ll soon have a house with a pool.

See how easy?

Right.

Of course, like all inspiration porn, the message is not directed at disabled people. It has an impact on us, of course. In this particular instance, the clear implication is that if we’re not able to make our hopes and dreams come true, it’s because we’re all the things that the average person mistakenly believes we are: narcissistic, angry, complaining, and lazy. But the graphic itself is directed at able-bodied people, with the aim of shaming them out of being upset at actual problems.

Usually, this shaming takes place by way of a visual image that shows a disabled person doing something that the average person wouldn’t imagine a disabled person could do. Like smiling. Or skiing. Or enjoying breakfast. You know, something incredibly heroic. But in this case, the disabled person is doing exactly what most people think disabled people do: sitting in a chair. In fact, you can barely see the disabled person, because the power chair takes up most of the frame. So what’s so inspirational here?

Nothing. In fact, the image of the disabled person is a warning:

You don’t want to be like him, DO YOU?

The visual image is counter-inspirational. It’s an example of who the viewer is exhorted not to be. In fact, at its most visceral level, the graphic is suggesting that the guy is in the power chair because he’s got a bad attitude. I mean, if the only disability in life is a bad attitude, then what’s the guy doing in a power chair? In the logic of the graphic, this guy must have so much bad attitude that he’s rendered himself unable to walk.

So let this be a lesson to all your able-bodied people griping about the fact that you lost your job, or you have no health insurance, or your spouse left you, or you’re one paycheck away from being on the street, or you live in a society in crisis. Quit complaining, do you hear me? Because things could be worse. You could be disabled. You could be like the guy in the power chair. And it would be your own damned fault.

Inspired yet?

Source

Quotesbuddy.com. http://www.quotesbuddy.com/attitude-quotes/the-only-disability-in-life-is-a-bad-attitude/. Accessed June 4, 2012.

© 2012 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg