The Sins Invalid Film: An Interview with Patty Berne and Leroy Moore

[The graphic consists of the face of a Leroy Moore looking upward and to the left. The left and right borders are drawn to look like the perforations in film negatives. Against a black background, the text reads: "Sins Invalid presents the Crip Soiree and Speakeasy. Poetry, song, and a preview of the Sins Invalid film! Friday 10/11, 7 pm, Saturday 10/12, 7 pm, 474 24th St., Oakland, CA."]

Sins Invalid is a performance project on disability and sexuality that makes central the work of queer artists, gender-variant artists, and artists of color. Over the past several years, Sins Invalid has been producing a film about its work. The Sins Invalid film will premiere in Osaka, Japan on September 14 and will be shown thereafter in venues around the US.

This past week, I interviewed two of the co-founders of Sins Invalid, Patty Berne and Leroy Moore, about the film, about their work, and about the ways in which Sins Invalid engages issues of disability, sexuality, and justice.

Rachel: What led you to create the Sins Invalid film?

Leroy: We wanted to get Sins‘ artistic and political vision and work beyond the Bay Area. We know that our community has grown nationally, even internationally, and while there’s nothing like a live performance, we wanted to make ourselves as accessible as possible for non-local community.

Patty: The power of the artists’ work really lays in the visual narratives as well as language. It’s important to see disabled bodies (however one defines that) actually embodying power and grace and sexual agency.

Leroy: There’s nothing like having full control of the context and the message both — and we are able to do that on stage and in many ways in film media as well.

Patty: We are being very thoughtful about where and how the film is shown, attempting to partner with community-based organizations to screen it. We are actually having our world premiere in Osaka Japan in a week!

Rachel: That’s so exciting! What will be the venue in Osaka? Where is the film being shown?

Patty: It will be shown as part of the Kansai Queer Film Festival at HEP Hall in Osaka. They invited me to attend and speak as well. They are interested in intersectionality and the potential for allegiance between those doing queer organizing and disability organizing. I’m specifically going to address relationships between gender justice and disability justice.

As a power chair user, I must admit to being very nervous about the ableist air transportation system. But I think it’s an amazing opportunity for disability justice frameworks to go international and for us to build relationship with queer folks with disabilities in Japan. And, it’s a particular honor for me, as I’m Japanese American. (My mother is from Kamakura and immigrated here in the 1940′s.)

Rachel: I’m glad you’re able to avail yourself of this opportunity. Intersectional discussions that include disability are crucial. As I watched the film, I found myself very interested in the process of how you put it together. When did you begin, and what was the process like as it unfolded?

Leroy: We began the film process in 2007 and have accumulated approximately 100 hours of footage.

Patty: As Leroy said earlier, we decided to document the work as a way to spread our vision and begin these conversations in broader sectors. Film has SUCH a broad reach. And as I said earlier, the visual narratives are as powerful as our language. But we had no idea what we were getting into really! I have so much respect for filmmakers! The medium is resource intensive and relatively unforgiving.

We’ve worked with 3 editors over the course of the 5 years, and finally really clicked with one in the last push toward completion.

Rachel: I’m so impressed both by the quality of the art depicted and by the film itself. It is all so beautifully done. Could you each speak to the ways in which the art of Sins Invalid serves the cause of disability justice, particularly in terms of disability and sexuality?

Patty: Thank you for appreciating the work! We live in a very visual age, where we are inundated, saturated by imagery. But most of that imagery reflects systems of oppression and the violence that supports it, slickly produced and packaged so that we consume it without reflecting on what narratives we are ingesting.

We decided to produce performance with high artistic merit because, as artists, that is important to us, but also because we are aware that disability imagery is perpetually used to reinforce our own oppression — charity programs like the MDA Telethon, the specter of the ghastly cripple as in David Lynch films, the tragic crip who serves the higher purpose through suicide as in Million Dollar Baby…

We need images of the truth — that we are powerful and complex and fucking HOT — not despite our disabilities but because of them!

In any movement, there is a need for artists to reflect the reality of the communities, and I think that’s what we’re doing. It’s also our responsibility to reflect the political imagination for what liberation could look like, so we seek to do that as well.

I think movements need a variety of formations — organizations who organize its base, think tanks and scholars and media, policy makers, cultural workers… And I like to think that Sins is doing that cultural work

We focus on disability and sexuality with in a disability justice framework specifically because sexuality is a human right, yet it is one of the most painful ways that we are dehumanized. We are neutered in the public eye (at least in this national context). We recognize our wholeness — including our lived embodied experience and our sexuality — and want to reflect that wholeness.

Leroy: I wanted to add that typically we see sexuality as something we do individually and privately, and we don’t usually see its impact on community. Sins breaks up the idea that sexuality is just an individual activity but brings sexuality into the conversation as a political issue to include as part of justice work. After all, it’s part of our oppression.

Rachel: Yes. One of the most powerful things about Sins Invalid is that it celebrates that disabled people have a lived experience of the body — that our bodies are not inert or inanimate. Given that human beings live in bodies, showing our lived experience is crucial for asserting our humanity.

With regard to justice work, what are the commonalities that you see in the struggle for social justice among marginalized peoples — particular among people of color, trans* and genderqueer people, disabled people, and queer folk — and how does Sins Invalid speak to these commonalities?

Patty: There are many commonalities and points of distinction. One of the primary commonalities is that a tactic of oppression used against all of us is that the oppression has been inscribed on our very skins — that our oppressions have been naturalized as a by-product of having a particular body — so that people think that what is difficult about being gender non-conforming, for example, is being in a non-conforming body, as opposed to being in a system of gender binary and heteronormativity. Or that what is difficult about being disabled is needing an accommodation, as opposed to living within ableism.

Another point of overlap is that our sexualities have been demonized and seen as vile or dangerous, and used as a way of engendering fear of us. Relatedly, our communities’ reproductive rights have been attacked through eugenic practices and programs.

All of the oppressed communities that you identified — communities of color, disability communities, trans/genderqueer communities, queer communities — we are all living within a white, able-bodied, heteronormative patriarchal capitalist context and struggle daily to live safely, with dignity. We each have struggles specific to our own experience of oppression, certainly, but the various systems of oppression reinforce each other and all manifest into all of our communities.

Leroy: And beyond a shared oppression, all of our communities have a rich culture — arts, music, poetry — and through our creation we can learn about each other and how we have each celebrated our own existences and spoken out against injustice. For example, there is a community of queer black women in the Blues that survived “isms” and created strategies for living and amplifying their artistic voice, and I think all communities can learn from that.

Rachel: I agree. One of the things that I appreciate about the work you do is that you go beyond critique into talking about how life can and must be. Along these lines, what kind of impact do you hope the film will have?

Patty: I think we are hoping for folks with disabilities who may not have thought about themselves as beautiful or sexy to see themselves in our work and to see their beauty. And for folks who may be functionally disabled but did not want to identify themselves as disabled due to stigma to perhaps feel a bit safer in rethinking the rigid line separating disabled from able-bodied. And for folks who love the work to move resources toward disabled artists!

And more deeply, to change the public debate about disability and sexuality so that it is a given that we have sexual agency, and that it is recognized that as people with disabilities we are also black and brown and queer and genderqueer and that we are not trading one identity for another. So that when we have a conversation about disability and sexuality, we are necessarily discussing our need for deinstitutionalization so that we can express our sexuality. So that when we discuss disability, we are necessarily addressing the incarceration of black men and the treatment of disabled prisoners. Does that make sense?

Rachel: Absolutely.

Patty: Our hope is that the film humanizes us — all of us.

Leroy: We hope that it will open doors of the heart and mind about what cultural work can look like, to go beyond identity politics alone to witness the diversity and strength of our communities. We hope that the film will be an educational tool for youth with disabilities, especially youth of color.

I hope that the film contributes to a cultural critique about people with disabilities and how we are represented in the media.

Patty: We are developing a study guide so that people can read articles or poems and have discussions in their own settings reflecting on the film and what it evokes for them.

Rachel: I hope that all of the work you’re doing will get people talking. Where will the film be screened, and where can people purchase a copy?

Leroy: We are trying to get into film festivals around the country and partnering with colleges and community based groups everywhere to get the film out initially. We are new members of New Day Films, who will be supporting our distribution. Pretty soon our film will be available for individual purchase at http://www.newday.com!

And in the Bay Area, folks should come out for our Crip Soiree and Speakeasy on October 11th and 12th at the New Parkway Theater in Oakland. You can get tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com/event/444189.

And if you are in Japan, go to the Kansai Queer Film Festival . Patty will be in Osaka screening the film and discussing our work on Sept. 14th! Sins goes international!

Patty: If anyone is interested in bringing the film to their campus or group, feel free to contact us at info@sinsinvalid.org. Or if you want to purchase an individual copy before New Day has it, drop us a line at info@sinsinvalid.org.

Rachel: Thank you both for taking the time to talk about Sins Invalid. Much success to you!

[Against a yellow background bordered by black lines with diamond designs at each corner, the text reads: "Sins Invalid celebrates the power of embodiment, disability and sexuality, by offering a vision of beauty that includes all bodies and communities.

[Against a yellow background bordered by black lines with diamond designs at each corner, the text reads: "Sins Invalid celebrates the power of embodiment, disability and sexuality, by offering a vision of beauty that includes all bodies and communities.

Come mingle, nibble and flirt at the Crip Soiree and Speakeasy, while artists Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Nomy Lamm, Maria Palacios, seeley quest and Leroy F. Moore, Jr. entice you with song and poetry following by a...

Preview screening of the Sins Invalid Film

7 pm on Friday, October 11th and Saturday, October 12th, 2013

at the Screening Room at the New Parkway Theater, 474 24th St. at Telegraph Ave., Oakland

Tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com/event/444189, $15-$100 sliding scale

ASL interpreted – Audio Description – Wheelchair accessible

Please refrain from using scented products

Please note: Film contains explicit content.

www.sinsinvalid.org | info@sinsinvalid.org | 510.689.7198

Sins Invalid is a fiscally sponsored project of Dancers' Group. We are grateful for the generous support of the Aepoch Fund, the Left Tilt Fund, the San Francisco Arts Commission, the Carpenter Foundation, the Horizons Foundation and the Fairy Godfathers Fun, Astraea Foundation, Community Foundation Boulder, Zellerbach Family Foundation and the Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation, the Dancer's Group New Stages for Dance Program, the Brown Boi Project, and each of our FABULOUS INDIVIDUAL DONORS AND KICKSTARTER BACKERS!!”]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

On the Murder of a Disabled Daughter

On August 19, an 88-year-old Oakland man named William Roberts killed his 57-year-old quadriplegic daughter Marion Roberts and then turned the gun on himself. Information about the case has been sparse, but it’s clear that Mr. Roberts was terminally ill with liver cancer and lung disease, and that he had cared for his daughter for over 25 years — first with his wife and then with his son. His daughter had become quadriplegic and had sustained traumatic brain injury from a fall in 1987. She needed assistance with all of the basic tasks of life, and it appears that she received that assistance with a great deal of love.

So what would drive a man to commit such an act at the end of his life?

I think about these kinds of issues a great deal. When a healthy parent, in the prime of life, kills a disabled child, my immediate response is to condemn the perpetrator. I do not want to hear about a lack of services, or about the perpetrator’s fear and hardships. No. You bring a child into the world and you are responsible for protecting the life of that child. That is my immediate response.

So I was surprised, as I read the story of William Roberts and Marion Roberts, that my response was not nearly so visceral. The gating issue, for me, was Mr. Robert’s terminal illness. His impending death seems to have been the motivator here, not his daughter’s disability. I see no evidence that he killed her because he wanted a “normal” life, or because he resented having a disabled daughter, or because he thought life had done him wrong. After all, he had cared for her for 25 years — into his 60s, 70s, and 80s.

I don’t know the man or the family, but it is possible that William Roberts killed his daughter because he was dying and he was terrified of leaving her in the hands of strangers. This is a fear that afflicts a great many parents of severely disabled children. And he had good reason to be terrified. His daughter was likely headed straight for substandard care in the disability gulag. Marion’s brother Thomas helped with her care, but it appears that the bulk of the caregiving fell on the father and that he was frightened about his increasing inability to care for her. Who knows whether anyone had stepped up to reassure him that they would be there after he died? Or whether he could trust those assurances even if they had come?

I’m beginning to realize the necessity of separating the responses to these stories — which inevitably follow the tired and bigoted logic of “disabled people are suffering and the parent/caregivers are putting them out of their misery” — from what might have been going on for the people involved. I don’t think that William Roberts killed his daughter because he thought she was suffering in the here and now. In fact, there is no evidence that she was suffering in the here and now, and there is no evidence that he thought she was. I think it’s possible that he killed her to prevent her from suffering abuse, neglect, loneliness, and indignity at the hands of uncaring strangers after he died.

The man was faced with an impossible choice on his daughter’s behalf: What is better? Death or hell? That someone who spent his elder years caring for his daughter would ultimately take her life (and his own) says far more about the world we live in than it says about him. I feel for this man in a way that I don’t usually feel for people who commit these murders. There was no good ethical choice here because the world didn’t leave him with one.

Is murdering your child an ethical choice? No. I can’t see how that’s arguable, ever.

Is leaving your adult child to be warehoused in hell an ethical choice? No. I can’t see how that’s arguable, ever.

The absolute lack of an ethical choice is not on William Roberts. It’s on the world.

To me, this is very different from a healthy person in the prime of life who kills a child and ends up being excused because they couldn’t get proper support services. Bullshit to that. Not getting proper support services while you’re in the prime of life is a very different thing from being tortured by what will happen after your death when your death is clearly around the corner. This man spent 25 years caring for his daughter and, by all accounts, did an outstanding job. His worry was not about a lack of support services when he was still alive. He could make up for that lack. But after he was dead — what then?

As I age, my greatest fear is to fall into the hands of strangers for my care. I do not fear pain, or further disability, or even death as much as I fear entering the medical system on my own. It is my worst nightmare. I think that it was likely William Roberts’ worst nightmare for his daughter.

Do I condone what William Roberts did? No. I don’t. A murder-suicide is ghastly. I don’t consider it a noble act.

Do I condone the unconscionable choice the world gave William Roberts? No. I don’t. I grieve for a world in which death or abandonment into hell are the choices people are given.

If my condemnation is going to fall, I’m going to let it fall on a world that creates these unconscionable choices.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Scapegoating Schizophrenia: Paul Steinberg’s Shameful New York Times Op-Ed Column

The scapegoating continues.

This week’s New York Times Op-Ed page features an utterly irresponsible article in which psychiatrist Paul Steinberg baselessly blames schizophrenia for mass shootings. In a truly chilling fashion, Dr. Steinberg argues that, in order to prevent such tragedies, we need to stop worrying our heads about the civil rights of people with schizophrenia:

[W]e have too much concern about privacy, labeling and stereotyping, about the civil liberties of people who have horrifically distorted thinking. In our concern for the rights of people with mental illness, we have come to neglect the rights of ordinary Americans to be safe from the fear of being shot — at home and at schools, in movie theaters, houses of worship and shopping malls.

Dr. Steinberg makes a pejorative and unsubstantiated association here between schizophrenia and the mass shootings that have taken place in 2012. He refers to shootings “at home and at schools” (a clear reference to the December 14 Newtown, Connecticut massacre), “in movie theaters” (a clear reference to the July 20 Aurora, Colorado theater shooting), “houses of worship” (a clear reference to the August 5 shooting at a Sikh Temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin), and “shopping malls” (a clear reference to the December 11 shooting at a shopping mall in Portland, Oregon).

Terrifying events, to be sure. But before we start tossing people’s civil liberties out the window, let’s look at whether any of the perpetrators of these violent acts actually had schizophrenia:

As far as we know, Adam Lanza, the Newtown shooter, was not diagnosed with schizophrenia, nor have we heard evidence that he was delusional.

James Holmes, the shooter in Aurora, saw a psychiatrist who specializes in schizophrenia — which means precisely nothing regarding his own diagnosis. Her practice was not limited to people with schizophrenia. He has not been diagnosed with the condition.

Wade Michael Page, who murdered six people at a Sikh Temple, was a racist skinhead who no one has ever remotely hinted showed signs of schizophrenia.

Jacob Tyler Roberts, who was responsible for the shooting at the mall in Portland showed no signs of delusional thinking to anyone around him, including his girlfriend.

But that doesn’t stop Dr. Steinberg from coming up with two new culprits:

At Virginia Tech, where Seung-Hui Cho killed 32 people in a rampage shooting in 2007, professors knew something was terribly wrong, but he was not hospitalized for long enough to get well. The parents and community-college classmates of Jared L. Loughner, who killed 6 people and shot and injured 13 others (including a member of Congress) in 2011, did not know where to turn.

Of course, Seung-Hui Cho was never diagnosed with schizophrenia in his lifetime. Psychiatrists like Dr. Steinberg have only done so post-mortem, and the more responsible ones acknowledge that they cannot make such a diagnosis with any certainty. The only mass murderer to whom Dr. Steinberg makes reference who has actually been diagnosed with schizophrenia is Jared Lee Loughner.

There are very good reasons that psychiatrists have to meet a client in person in order to render a diagnosis: second- and third-hand testimony is notoriously unreliable, and diagnostic assessments can take days to complete. Oddly enough, Dr. Steinberg seems to be aware that he is breaking the ethical standards of his profession by diagnosing people he has neither met nor treated:

I write this despite the so-called Goldwater Rule, an ethical standard the American Psychiatric Association adopted in the 1970s that directs psychiatrists not to comment on someone’s mental state if they have not examined him and gotten permission to discuss his case. It has had a chilling effect. After mass murders, our airwaves are filled with unfounded speculations about video games, our culture of hedonism and our loss of religious faith, while psychiatrists, the ones who know the most about severe mental illness, are largely marginalized.

As far as I can see, the only “unfounded speculations” here are coming from Dr. Steinberg. It is hard to imagine how an affluent psychiatrist in private practice could imagine himself to be “marginalized,” particularly when it comes to armchair diagnoses. Given that his entire piece further marginalizes an entire group of people who already far more likely to be the victims of violent crime than to be the perpetrators, the term rings especially hollow.

To his credit, Dr. Steinberg does acknowledge schizophrenia is not generally associated with violence, though he then turns around and contradicts himself:

The vast majority of people with schizophrenia, treated or untreated, are not violent, though they are more likely than others to commit violent crimes.

Dr. Steinberg rather skews the evidence here. In fact, people with schizophrenia are not more likely to commit violent crime when one factors in the presence of substance abuse. A PLoS study found that, when controlling for the presence of drug and alcohol abuse, people with psychosis are no more likely to commit violent crime that people without psychosis:

Importantly the authors found that risk estimates of violence in people with substance abuse but no psychosis were similar to those in people with substance abuse and psychosis and higher than those in people with psychosis alone. (Gulati et al. 2009)

In other words, people with no psychosis who abuse alcohol and drugs have a higher risk of committing a violent crime than people with psychosis who do not abuse alcohol and drugs, and a similar risk to people with psychosis who do. The factor to be looking at is drug and alcohol abuse, not schizophrenia.

That point seems to have been lost on Dr. Steinberg. He should know better. Shame on him.

References

ABC News. “Clackamas Town Center Shooting: Who Is the Alleged Shooter?” http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/video/clackamas-town-center-shooting-jacob-roberts-alleged-shooter-17959547. December 13, 2012. Accessed December 27, 2012.

The Atlantic. “Diagnosing Adam Lanza.” http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2012/12/diagnosing-adam-lanza/266322/#. December 13, 2012. Accessed December 27, 2012.

Billeaud, Jacques. “Trial not likely for Jared Lee Loughner in 2012.” Boston.com, January 6, 2012. Accessed December 27, 2012. http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2012/01/06/trial_not_likely_for_jared_lee_loughner_in_2012/.

Gulati, Gautam, Louise Linsell, John R. Geddes, and Martin Grann. “Schizophrenia and Violence: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” PLoS Med 6, no. 8 (2009). doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000120.

Laris, Michael, Jerry Markon, and William Branigin. “Wade Michael Page, Sikh temple shooter, identified as skinhead band leader.” The Washington Post, August 6, 2012. Accessed December 27, 2012. http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2012-08-06/world/35491487_1_end-apathy-sikh-temple-skinhead-band.

PBS News Hour. “Alleged Colorado Shooter Saw Schizophrenia Expert.” http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/social_issues/july-dec12/colorado_07-27.html. July 27, 2012. Accessed December 27, 2012.

Psychiatric News Alert. “People With Schizophrenia More Likely to Be Victims, Not Perpetrators of Violence.” http://alert.psychiatricnews.org/2012/05/people-with-schizophrenia-more-likely.html. May 10, 2012. Accessed December 27, 2012.

Steinberg, Paul. “Our Failed Approach to Schizophrenia.” The New York Times, December 25, 2012. Accessed December 27, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/26/opinion/our-failed-approach-to-schizophrenia.html?_r=0.

Welner, Michael. “Cho Likely Schizophrenic, Evidence Suggests.” ABC News, April 17, 2007. Accessed December 27, 2012. http://abcnews.go.com/Health/VATec h/cho-schizophrenic-evidence-suggests/story?id=3050483#.UNxJWnfLBQF.

© 2012 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Where Are the Elders with Autism? Reflections Upon Reading Fred Pelka’s What We Have Done

Following is my third and final critical annotation of the semester.

—

Before I began reading Fred Pelka’s What We Have Done: An Oral History of the Disability Rights Movement, I’d expected that, in order to keep myself from drowning in dry historical detail, I’d have to pick and choose my way through its 600-plus pages. I was pleasantly surprised, then, to find myself reading the book into the wee hours of the morning as though it were a novel. What We Have Done combines an exhaustive rendering of historical events — the who, why, what, when, where, and how of the disability rights movement — with first-person accounts by the people who played leading roles in it. An independent scholar and the author of The ABC-CLIO Guide to the Disability Rights Movement, Pelka artfully weaves the voices of disabled activists through his historical narrative, giving form to the principle that underlies the disability rights movement: Nothing about us, without us. The result is a work that covers the framing of disability as a civil rights issue from the founding of the National Federation for the Blind (NFB) and the American Federation of the Physically Handicapped (AFPH) in 1940 through the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990.

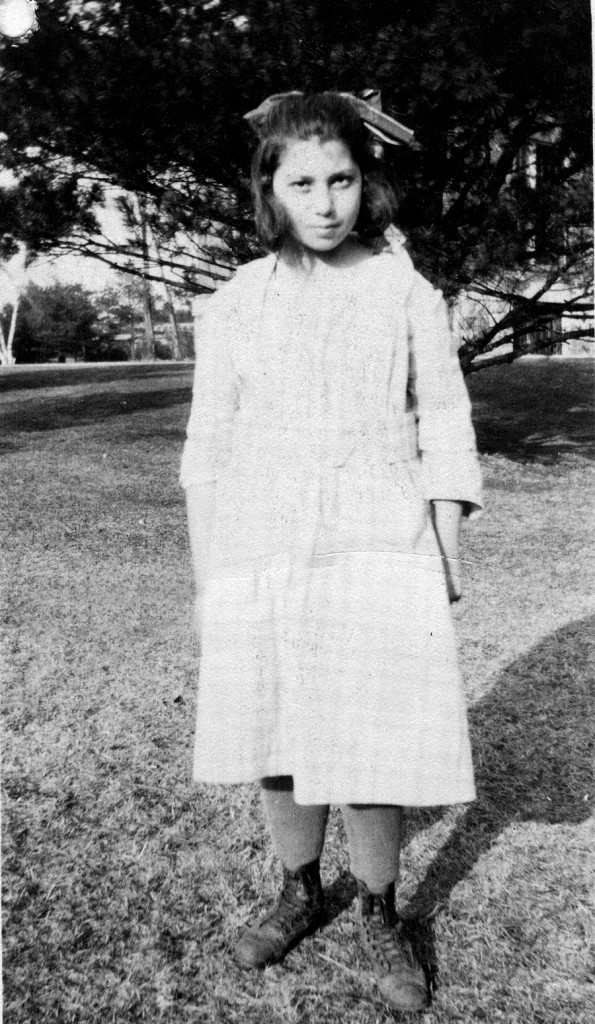

For me, the most compelling material in Pelka’s book concerns the institutionalization of disabled people. I have a personal interest in this subject: my great-aunt Sarah, who was autistic and had cerebral palsy, was incarcerated in Massachusetts state institutions for most of her short life and died of tuberculosis in the Foxborough State Hospital in 1934, at the age of 25. Placed in institutional care at the age of eight, Sarah was forgotten for generations until I discovered her on a census form 75 years after her death (Disability and Representation 2012). I now have a passion for bringing the conditions of her life out of the shadows and honoring her as an autistic and disabled person. I am always shocked, then, to hear people say that autism is an entirely new condition that didn’t exist in past generations. When I hear such things, I feel as though my great-aunt has been relegated to obscurity a second time.

In reading Pelka’s book, though, I found a wealth of historical information that helps to explain exactly why autistic people like my great-aunt Sarah were invisible in their day and why their lives are still invisible now. Central to our cultural forgetting was the eugenicist argument that disabled people were a physical and moral threat to society; this belief resulted in their segregation and institutionalization. One of the reasons that institutionalization became the only option for many was that, until 1975, disabled children did not have a legally protected right to attend the public schools. Thus, many of them were placed into institutions in which abuse, squalor, and disease made their already vulnerable lives all the more fragile, and from which few emerged, except in death.

One of the people who has been most vocal about the purported impossibility of autistic people existing in large numbers before the current generation is Anne Dachel, media editor for the organization Age of Autism. Along with her colleagues, Ms. Dachel believes autism to be a recent “epidemic” caused by vaccination (Age of Autism 2012). She claims that because one doesn’t find a great many elders with autism in our nursing homes, autism as we now know it did not exist in past generations. In a blog post this past July, Ms. Dachel challenges us to explain where all the autistic elders are:

PLEASE SHOW US THE MISDIAGNOSED, UNDIAGNOSED 40, 60, and 80 YEARS OLDS WITH AUTISM. I don’t mean ones with what could be termed high functioning or Asperger’s. I don’t mean autistic adults like the ones they supposedly found in Great Britain who were able to answer survey questions. I want to see the people in our nursing homes and institutions who display the same signs of classic autism that we see in so many of our children. I want to see adults who are non-verbal, in diapers, and flapping their hands endlessly. I want to see autistic adults who’ve endured years of the seizures, sleep disorders, bowel disease and life-threatening allergies that so many of our autistic children have. I want to see adults whose history includes regression—adults who were born healthy and were developing normally until they suddenly and dramatically lost learned skills, started stimming and lost eye contact. This is what countless thousands of children with autism have gone through. SHOW US THESE SAME ADULTS. (Anne Dachel: Autism and the Media 2012)

Of course, the idea that someone could go to a nursing home as an elder implies that the person was once a part of a community. It is ironic, then, that Ms. Dachel is looking for people born between 1930 and 1975 — years in which disabled people, far from being integrated into their communities, were ruthlessly segregated from society, denied the right to an education, and consigned to a “disability gulag,” where they underwent enormous suffering, deprivation, and abuse (Pelka 2012, 49).

In order to understand why one doesn’t find large numbers of autistic adults in our nursing homes, one must begin by noting the degree to which disabled people were incarcerated and otherwise kept out of public view for much of the twentieth century. In the early part of the century, the eugenicist notion that disabled people were responsible for all the problems of society put disabled people in state institutions (Pelka 2012, 9). People with disabilities were considered a social evil that would destroy society just as disease would destroy a body (Pelka 2012, 11). They were therefore quarantined, kept away from nondisabled people, and stripped of their right to travel freely and to associate with others. As attorney Tim Cook explains:

[I]n virtually every state, in inexorable fashion, people with disabilities — especially children and youth — were declared by state lawmaking bodies to be unfitted for companionship with other children,’ a ‘blight on mankind,’ whose very presence in the community was ‘detrimental to normal’ children, and whose ‘mingling… with society’ was ‘a most baneful evil.’ Persons with severe disabilities were considered to be ‘anti-social beings’ as well as a ‘defect…[that] wounds our citizenry a thousand times more than any plague.’ In conclusion, then, ‘persons with disabilities were believed to simply not have the ‘rights and liberties of normal people.’ (Pelka 2012, 11)

Until the 1960s, when autism was finally defined as a condition distinct from psychosis and schizophrenia (Fombonne 2003, 1), autistic people like my great-aunt Sarah were misdiagnosed with mental illness. In fact, Sarah had diagnoses of both intellectual disability (she was diagnosed as a “moron”) and “dementia praecox,” the old term for schizophrenia (Disability and Representation 2012). People like her would have had no hope of escape from an institution — not into a nursing home, not into a group home, and not into a private home. As Pelka notes: “Because the consensus of ‘expert opinion’… was that people with disabilities, particularly those labeled ‘mentally retarded’ or ‘mentally ill,’ should be institutionalized, having a disability often meant lifelong imprisonment” (Pelka 2012, 48).

One of the social conditions that made institutionalization possible was a series of laws, in almost every state, that kept children with disabilities out of the public schools; such children, according to attorney Thomas K. Gilhool, were considered “uneducable and untrainable” (Pelka 2012, 139). Moreover, laws in some states even allowed school superintendents to take children out of their homes, against the will of their parents, and place them in institutions (Pelka 2012, 139). These institutions represented a powerful lobbying group that, according to Pelka, “actively impeded the development of community-based services and integrated public school education” (Pelka 2012, 49). Such a situation did not find remedy until the 1971 consent decree issued in the case of PARC v. Pennsylvania, which found that all children have a right to a free public education (Pelka 2012, 26). This court case ultimately resulted in the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, the precursor to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (Pelka 2012, 137). Thus, one did not see many children with autism in the public schools until after 1975 because, until then, they did not have a legal right to access a free public education. The only alternative for many children was institutionalization.

Once institutionalized, children lived in conditions that made it unlikely that they would ever survive to old age or leave the facility. The late Gunnar Dybwad, an attorney and, from 1957 to 1963, the executive director of the National Association for Retarded Children, had extensive knowledge of what befell disabled people in state care from the 1930s through the 1960s. In Pelka’s book, he describes the nightmarish conditions in state institutions, including the overcrowding, the stench of human feces, the unbearable levels of noise, and the food unfit to eat (Pelka 2012, 50-51). No one made an effort to separate children from adults (Pelka 2012, 51), and sexual abuse was rampant (Pelka 2012, 52). No oversight from state or federal agencies was in place (Pelka 2012, 51), resulting in situations in which “no one… was safe and secure” (Pelka 2012, 53) and in which children were “brutally beaten” (Pelka 2012, 53). Parents were not allowed into the facilities to see the living conditions of their children (Pelka 2012, 52) and had no idea of what was happening to them. For decades, health professionals countenanced the misery at these institutions, leading Dybwad to note that “it might be appropriate if [mental retardation professionals] started each annual meeting with a session where they would confess their sins. Because they all knew what was going on, and they never did anything about it” (Pelka 2012, 51).

Such conditions lasted well into the 1970s. Richard Bronston, a physician who worked at the Willowbrook State School and Hospital on Staten Island describes a situation of “[w]retchedness and suffering and insanity and inhumanity” (Pelka 2012, 180). The residents at Willowbrook, he remembers, lived in an environment in which they experienced rampant disease, serious injuries, constant noise, rashes from caustic floor cleaners, burns from falling asleep against the radiators, and amputations due to fungal infections (Pelka 2012, 176-178). Physical assault, sexual abuse, and pregnancy due to rape were common (Pelka 2012, 179). Far from having the opportunity to live to old age and graduate to nursing home care, residents at Willowbrook were “statistically more likely to be assaulted, raped, or murdered than in any other neighborhood in New York City” (Pelka 2012, 175). In fact, toward the end of his tenure, Bronston oversaw a ward with “a death rate that was nine times the death rate of the city of New York” (Pelka 2012, 179). It is unlikely that most autistic adults with the symptoms of which Ms. Dachel speaks — “seizures, sleep disorders, bowel disease and life-threatening allergies” — could survive to old age in such conditions (Anne Dachel: Autism and the Media, 2012). If Ms. Dachel would like to know where these adults are, I invite her to visit the cemeteries on the grounds of former state institutions. She will very likely find them there.

When I was a child growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, the only disabled children I knew in the public school system were diagnosed as “mildly mentally retarded.” I never knew any nonverbal autistic children. I never knew any children who used wheelchairs. I never knew any blind or deaf children, and I never knew any children with acute mental illness. These children were invisible to me not because they did not exist, but because most of them existed elsewhere, in a world apart. Some went to separate schools for disabled children, some remained at home, and many suffered in institutions. “Out of sight, out of mind” was the paradigm by which disabled people in past generations were segregated and incarcerated. Let us not forget them now.

References

Age of Autism. “A Letter from the Editor.” http://www.ageofautism.com/a-welcome-from-dan-olmste.html. Accessed November 6, 2012.

Anne Dachel: Autism and the Media. “The Boston Globe covers up autism.” http://annedachel.com/2012/07/25/the-boston-globe-covers-up-autism/. July 25, 2012. Accessed November 6, 2012.

Disability and Representation. “Reclaiming Memory: Searching for Great-Aunt Sarah.” http://www.disabilityandrepresentation.com/2012/10/30/reclaiming-memory-searching-for-great-aunt-sarah/. October 30, 2012. Accessed November 6, 2012.

Fombonne, Eric. “Modern Views of Autism.” The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry (September 2003): 1-4. http://ww1.cpa-apc.org:8080/publications/archives/cjp/2003/september/guesteditorial.asp.

Pelka, Fred. What We Have Done. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012.

© 2012 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

The R-Word and Why It Matters: The Case of Jenny Hatch

Jenny Hatch and Kelly Morris

The Internet was ablaze with outrage two weeks ago when Ann Coulter saw fit to call the President of the United States a retard, and when, in an interview with Piers Morgan, she dismissed the concerns of disabled people, our loved ones and, well, anyone with any moral awareness at all by suggesting that retard is just another word for loser. When Mr. Morgan countered that using the word as a pejorative implies that disabled people are less than worthy, Ms. Coulter argued shamelessly that no one calls disabled people retards anymore.

How this woman has a public platform anywhere outside of a soapbox in a public park is beyond me.

I’m sick of Ann Coulter. You’re sick of Ann Coulter. The only person who isn’t sick of Ann Coulter is probably Ann Coulter. So I can understand it when people say we shouldn’t keep talking about Ann Coulter’s use of the R-word, because it just gives her the attention she craves. I can understand the impulse to ignore her, believe me, but it’s not going to solve the problem. Hate speech is hate speech, and it has power. Ignoring Ann Coulter may starve her of attention, but it’s not going to starve the word of its power. It’s not going to stop hate speech from wreaking its havoc.

Let’s see what happens when the word retard becomes synonymous with the word loser. Let’s see just how much people lose.

—

Jenny Hatch is a 28-year-old Virginia woman with Down Syndrome. Until this past August, Jenny was working, going to church, and integrating herself fully into her local community of Newport News, where she had lived all her life. She has now been placed under the temporary guardianship of Jewish Family Service (JFS) of Tidewater in a group home in Portsmouth, many miles from all that is familiar to her, and against her clearly expressed wishes to remain in the community and to live with her friends and employers, Jim Talbert and Kelly Morris.

As though these violations of her civil rights were not enough, Jenny has had to endure more: Her temporary guardian has confiscated her computer and her cell phone, has kept from her job and from her church, and has denied her contact with Jim and Kelly. In violation of her rights as a citizen and as a human being, Jenny is being stripped of the right to use her voice, to associate freely with others, and to have her preferences respected.

Over the past week, I have been working with Jim and Kelly on a Change.org petition to prevail upon Bill Hazel, the Virginia Secretary of Health and Human Services, to restore Jenny’s rights and to bring her home. In the process, I have become very familiar with the details of her story.

According to a WAVY-10 news report by Andy Fox, Jenny began working in Jim and Kelly’s thrift store in 2008. Jenny has also been a lifelong member of the local Methodist Church, worked on local political campaigns, and was well-known and well-loved in town. In an October 22 article in the Daily Press, Joe Lawlor reported that, until this past August, Jenny was a working, thriving member of the community:

She worked part-time at Village Thrift stores in Newport News and Hampton, about 20 hours a week. She had her own bank account, did her own laundry, can read and write and use social media on the Internet, cook simple meals and take ‘two showers per day,’ according to her friends.

So how did Jenny come to lose everything?

In a statement on the Care2 Petition Site, Jim and Kelly explain that, in January of 2012, Jenny told them that her mother and stepfather had asked her to leave the home she shared with them. She briefly went to live with someone who was never home and where she did not feel safe. In March of 2012, while riding her bicycle, Jenny was hit by a car. Her injuries required back surgery, and she remained in the hospital for a week. Because Jenny’s mother and stepfather were not willing to care for Jenny when she was discharged from the hospital, Jenny had nowhere to go. At that point, Jim and Kelly took her into their home to care for her during her recovery and began the process of putting services in place.

The battle that ensued has resulted in a nightmare for Jenny and for those who love her.

Jim and Kelly have stated that the local Community Services Board (CSB) told them that it would not provide a Medicaid waiver to help keep Jenny in the community unless she was homeless. To get the services to which Jenny was entitled by law, Jim and Kelly surrendered her to the CSB. They considered the surrender to be purely pro forma and fully trusted that Jenny would return to their home with services in place. Instead, the CSB placed Jenny in a group home. Jenny was traumatized. Several times, Jenny made very clear her desire to leave and to return to Jim and Kelly’s home. In response, the facility staff abrogated Jenny’s civil rights by taking away her cell phone and her computer, and by telling her that she could not use the group home’s telephone.

On the Justice for Jenny Facebook page, Jim and Kelly explain the details of what transpired next:

They cut us off completely from any communication with Jenny and Jenny to us or her co-workers. At this point Jenny still had the legal right to make her own decisions. Once Jenny spoke with Stewart Prost, a Human Rights Advocate with the Dept of Behavioral Health, he got involved and Jenny was now able to contact us once again. Jenny begged us to “please get me out of here” … We asked and pleaded with the CSB to place her in Newport News or Hampton where she could return to work and be close to the community that she loved. The case worker informed us that this “was her final placement.” We asked her why they are not trying to get her closer to everything she knows and we were told that they could no longer talk to us about Jenny. Even though Jenny had signed papers with the CSB giving permission for them to share information with us they still refused and blocked us out.

Jim and Kelly found an attorney for Jenny named Robert Brown, who was able to get Jenny free of the group home:

Jenny called Mr. Brown and asked him to help her. Mr Brown went to meet with Jenny to evaluate if she was competent to sign a power of attorney making us as agents. After the power of attorney was signed on August 6th she told the lawyer that she wanted to go home and Mr. Brown advised the case worker that Jenny was leaving.

Jenny returned to live with Jim and Kelly at their home. Shortly thereafter, Jenny’s mother and stepfather, who did not want Jenny in their home, filed a petition to place Jenny under state guardianship. At that point, although Jenny had not been ruled incompetent to make her own decisions, the court gave JFS of Tidewater temporary guardianship. JFS put Jenny in another group home, where she remains, cut off from communication with her friends, cut off from her work and her church, cut off from everyone she knows.

Jim and Kelly’s worst fear is that Jenny will feel that they have forgotten her.

—

The guiding principle of the disability rights movement is “Nothing about us, without us.” Jenny’s wishes are clear, but they have been ignored. According to the article in the Daily Press, Jenny’s self-advocacy at the court hearing granting temporary guardianship to JFS resulted in her removal from the proceedings:

She attempted to speak for herself at a hearing in Newport News Circuit Court on Aug. 27, but was shut down, according to court transcripts:

“I don’t need guardianship. I don’t want it,” Hatch said. For interrupting the proceedings, Circuit Court Judge David Pugh had her removed from the courtroom.

After a new hearing in which the judge maintained the temporary guardianship order, Jenny could be heard wailing outside in the street. According to the same article:

After an Oct. 11 Newport News Circuit Court hearing that maintained Jewish Family Services temporary guardianship over Hatch and kept her in a group home, Hatch held onto a street sign outside the courthouse, screaming and crying that she wanted to return to the couple’s home, Talbert and Morris said.

And in an interview with WAVY-10 News later in October, Jenny quite clearly stated her wishes:

I am sad because it’s heart breaking, and I want to be with Jim and Kelly.

According to the law, it is the responsibility of state agencies and professionals to provide Jenny with the support to live independently in the least restrictive setting. When the Supreme Court ruled against the state of Georgia in Olmstead v. L.C. and E.W., justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg penned the decision of the court, saying that Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act requires public agencies to provide services in the community whenever possible:

In the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), Congress described the isolation and segregation of individuals with disabilities as a serious and pervasive form of discrimination. 42 U.S.C. § 12101(a)(2), (5). Title II of the ADA, which proscribes discrimination in the provision of public services, specifies, inter alia, that no qualified individual with a disability shall, “by reason of such disability,” be excluded from participation in, or be denied the benefits of, a public entity’s services, programs, or activities. §12132. Congress instructed the Attorney General to issue regulations implementing Title II’s discrimination proscription. See §12134(a). One such regulation, known as the “integration regulation,” requires a “public entity [to] administer … programs … in the most integrated setting appropriate to the needs of qualified individuals with disabilities.” 28 CFR § 35.130(d) (emphasis added)

For many disabled people, living independently does not mean being able to do everything without assistance. It means having the support in place to maximize independent choices, opportunities, and freedoms. That support isn’t happening in the case of Jenny Hatch, and its absence ought to send a chill wind through everyone. Everyone is one illness, one injury, one accident, one twist of fate away from being treated like a second-class citizen.

Disability isn’t just a medical issue. It’s a civil rights issue. It’s in everyone’s best interest to recognize it as such.

Please don’t turn away. Please sign the petition at Change.org demanding justice for Jenny, and share her story widely on all of your social media, blogs, and sites.

Let’s restore Jenny’s rights. Let’s bring Jenny home.

© 2012 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Reclaiming Memory: Searching for Great-Aunt Sarah

Following is a post I wrote in January of 2011 on my Journeys with Autism blog. I have been thinking a great deal lately about Sarah. I want to honor her by telling her story here.

—

In 2009, while searching Ancestry.com for new information to add to my family genealogy, I discovered the existence of a relative about whom no one in the family had ever spoken. She was my paternal grandfather’s younger sister (my father’s aunt), and her name was Sarah. During a search of census records, I learned that she had been a patient at the Massachusetts State Hospital in Canton, MA in 1920, when she was 11 years old, and at the Wrentham State School in 1930, when she was 21. In other words, she appeared to have resided in state institutions from the time she was a child.

My father’s family has a rather unusual last name, so when I came upon Sarah, I felt fairly certain that she was related to us. Because the state schools were often warehouses for people with physical and mental disabilities, I felt from the beginning that Sarah had been “disappeared” from the family because she had been disabled.

In the face of this attempt to erase her from memory, I began a quest to learn everything I could about Sarah and to bring her into the light of day.

I was saddened by everything I found.

Sarah’s father, apparently, was known as “vigorous, gregarious, a hard drinker and a gambler, and inclined to shirk family responsibilities.” Her mother, on the other hand, was described as “mentally incompetent, elusive, and uncooperative.” I’m not sure that Sarah’s mother was actually any of those things, since living with a hard drinker and gambler who chronically refused to take care of his family very likely explained how she presented to the rest of the world.

It’s clear that the family was desperately poor, as evidenced by their contact with various social service agencies throughout the 1920s, and by the placement of two of Sarah’s younger sisters with foster families during the 1930s. There were, in all, seven children who survived early childhood. Four others died very young. Sarah was the second eldest of the surviving children, having been born in 1908.

I soon found out that she was, indeed, physically disabled, and had been diagnosed with “congenital spastic paralysis,” now known as cerebral palsy, when she was very young. But even more interesting are the possible markers of autism: she was a nervous baby, cried continually, tore at her hair, scratched her face unmercifully, and first talked at 4 years of age.

In 1915, at the age of 7, Sarah was placed in a family home with another disabled child. In September of that year, she began in the first grade at the local public school.

In 1916, she was placed in a state home—the Massachusetts Hospital School in Canton, MA—because her foster mother could no longer afford to take care of her. A teacher at this school considered her to be “of slow mind, lacking in concentration, and having problems with attention.” (ADD, anyone?) In a painful example how easily disabled people are dismissed, it was suggested that Sarah be placed in a school for the feebleminded when she was older.

By 1920, the people at the Massachusetts Hospital School said that they could do no more for her. She was judged “not mentally competent” to compete with the children in her grade. It appears that she was placed in another family home before a space opened up for her at the Wrentham State School.

She entered the Wrentham State School in 1921, at the age of 12, with the hideous diagnosis of “moron.” As I look at a photograph of her taken around that time, I find myself amazed that anyone could have missed the focused, sad intelligence in her eyes. In fact, when I first saw the photograph, I burst into tears. She was the only person in the family whose eyes, whose facial expression, and whose look of anger and sadness at the insanities of the world reminded me so thoroughly of my own.

About 10,000 people were institutionalized at Wrentham during its history. Despite Sarah’s diagnosis, she was described as adapting herself very quickly to her surroundings, expressing herself relatively well, and displaying a full range of emotions. Apparently, she always tried to do her best and took pride in neat work—words that would have perfectly described me as a child. She was also a good singer—another trait that we share in common.

Unfortunately, Sarah began to fall apart in the late 1920s. She began to behave and talk in “peculiar” ways, becoming depressed and unhappy. She felt teased by her peers. She lost her appetite for food, and her behavior became disruptive. One can only guess at what she was going through. Had she been assaulted? Had she collapsed under the weight of chronic institutionalization? Had her longing for friends, family, and home finally become more than she could bear? We will never know.

She showed no evidence of being delusional and yet, when she left Wrentham in 1930 and entered the Foxborough State Hospital, she was given a diagnosis of “dementia praecox,” the now-defunct term for schizophrenia. It was certainly not unusual for autistic people, especially women, to be misdiagnosed with schizophrenia and other mental disorders, especially when the process of institutionalization itself created mental and sensory breakdowns. As a state mental institution, Foxborough was a dumping ground not just for physically and mentally disabled people, but also for poor non-disabled children and recalcitrant wives. In those days, it was not unusual for poor children to be placed in institutions, and for rich people to take them out and hire them as maids.

Sarah, however, never had this dubious opportunity. Instead, she entered the Foxborough State Hospital at the age of 21 and never came out. She died of tuberculosis of the lungs in 1934, when she was 25 years old. When I received a copy of her death certificate, I was horrified to learn that she had been ill with tuberculosis for ten months before she died. Ten months, suffering in hell with a wasting disease. It makes me physically sick to think about it.

Under most circumstances, the indignities visited upon the patients at Foxborough followed them into death. In general, the inmates (for that is what they were) were buried on hospital grounds, their graves marked not with their names, but with their patient numbers. As a result, if anyone in a later generation were to visit his or her deceased relative, it would be impossible to know where to look.

I was determined to honor Sarah by visiting her grave, and when I wrote to the state mental health agency to find out her patient number, I was surprised to learn that she had not been buried at Foxborough at all, but in the Arbeiter Ring (Workman’s Circle) cemetery in Boston. I have no idea who got her out of Foxborough to bury her properly, but I hope that the person is reaping untold benefits in heaven for this act of humanity. There is a non-profit agency that oversees all the old Jewish cemeteries in Boston, so I wrote to them right away to see whether they would send me a photograph of Sarah’s grave. To my dismay, I learned that there was no grave marker at all.

So Bob and I decided to get Sarah a proper grave marker, which was placed this past fall. On the marker appear her name, her date of birth, her date of death, and my favorite line from Psalms: Those who sow in tears shall reap in joy.

I hope that she has found joy in the next world.

I hope that she feels the peace of knowing that she has the dignity of a marked grave.

I hope she knows that her picture has taken its place on our wall, along with those of our other ancestors.

I hope it heals her that I am telling her story and making sure that people remember the shame and injustice of what happened to her.

My Hebrew name is now “Rachel Batya bat Sarah Channa”—Rachel Batya, daughter of Sarah Hannah. I have taken Sarah as my spiritual mother. Every Friday night at our Shabbos table, I receive a blessing, and her name is blessed with mine. She never had a chance to have a child of her own, but in some way that I don’t entirely understand, I am her daughter. I am a disabled woman, born into the same family two generations later, and I have what she didn’t have. I have the power to stand up and say, “No more.”

No more dismissal. No more shame. No more isolation. No more disappearances. No more silence.

No more Aunt Sarahs.

Not now. Not ever.

© 2011, 2012 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg