Speaking Love and Anger: A Response to Ngọc Loan Trần’s “Calling IN: A Less Disposable Way of Holding Each Other Accountable”

There are many things I like about Ngọc Loan Trần’s article Calling IN: A Less Disposable Way of Holding Each Other Accountable. I’m particularly struck by the author’s insistence that, within social justice spaces, we be kind to one another — that we acknowledge that each of us is ignorant, that we understand that we are all debriefing from the constructs in which we were raised, and that we support each other as human beings as we go forward to create justice:

We fuck up. All of us. …. But when we shut each other out we make clubs of people who are right and clubs of people who are wrong as if we are not more complex than that, as if we are all-knowing, as if we are perfect. But in reality, we are just really scared. Scared that we will be next to make a mistake. So we resort to pushing people out to distract ourselves from the inevitability that we will cause someone hurt.

And it is seriously draining. It is seriously heartbreaking. How we are treating each other is preventing us from actually creating what we need for ourselves. We are destroying each other. We need to do better for each other.

We have to let go of treating each other like not knowing, making mistakes, and saying the wrong thing make it impossible for us to ever do the right things.

And we have to remind ourselves that we once didn’t know. There are infinitely many more things we have yet to know and may never know.

…

I want us to use love, compassion, and patience as tools for critical dialogue, fearless visioning, and transformation. I want us to use shared values and visions as proactive measures for securing our future freedom. I want us to be present and alive to see each other change in all of the intimate ways that we experience and enact violence.

This is all absolutely beautiful, and I am so happy to see someone talking about it. I am unbelievably tired of the verbal violence that passes for dialogue, particularly in social justice spaces, and anyone who pleads for coming from a place of love and empathy mixed with anger and pain is a person after my own heart.

But there are a couple of things about the article that call me up short. One of them is the way in which the author talks about people having “strayed.” There is something about that idea that feels both deeply foreign and painfully authoritarian to me. The concept appears in the following context:

I picture “calling in” as a practice of pulling folks back in who have strayed from us. It means extending to ourselves the reality that we will and do fuck up, we stray and there will always be a chance for us to return. Calling in as a practice of loving each other enough to allow each other to make mistakes; a practice of loving ourselves enough to know that what we’re trying to do here is a radical unlearning of everything we have been configured to believe is normal.

There is a Christian paradigm here of “straying from the fold” that I find very troubling. I don’t come from a Christian background of bringing people back into the fold; I come from a Jewish background in which we already belong and are free to disagree. So, in the context of the piece, what exactly is the ideology from which people “stray”? Who decides? Is it necessary to think about a central ideology around which we must all constellate, or should there be more room for critique, for disagreement, for generative argument? Straying assumes that we must come back to center. But whose center? Mine? Yours? Any group that treats me as though I’ve “strayed” is likely a group that I will “stray” right out of, never to return.

My other issue with the piece is that it is directed only to people inside social justice communities. There is not necessarily a problem with this approach, per se. After all, making sure our own communities are functional is a prerequisite for trying to create a more just and loving society. But I’m also aware of the necessity of applying “love, compassion, and patience as tools for critical dialogue, fearless visioning, and transformation” with people who are outside of social justice communities — with people who haven’t heard our critiques of the status quo, who haven’t examined their own complicity in oppressive systems, who haven’t done the reading or had the discussions or entered into the discourses that are so familiar to us. To me, this is the real challenge. How do we call people in who are way outside of our communities without exhausting ourselves, getting run over, or compromising what we believe in?

I believe it’s possible. I believe that we can combine love, compassion, patience, anger, outrage, pain, and despair as we talk with others who are outside of our circles. If we don’t combine all of these feelings — if we’re only in a place of anger and outrage, or we’re only in a place of love and compassion — we’re living at the polarized extremes that our society has taught us are normal, expected, and beyond critique. We’re creating either endless war or a false peace.

We can do better. We must do better.

Reference

Trần, Ngọc Loan. “Calling IN: A Less Disposable Way of Holding Each Other Accountable.” Black Girl Dangerous. December 18, 2013. Accessed January 1, 2014. http://www.blackgirldangerous.org/2013/12/calling-less-disposable-way-holding-accountable/.

© 2014 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

How Do You Define Activism?

[I originally posted this piece to my old Journeys with Autism blog in April of 2012. The subject of activism and disability came up in a conversation today with several other disabled people, so I'm reposting the piece here as a point of discussion.]

How do you define activism?

I’ve been chewing on this question for awhile. It’s come up for me lately in the context of my graduate course. We are being asked to talk about the social relevance of our work, with an eye to bringing together theory and practice.

I find myself balking at the dualism of theory and practice. Surely, at least in the case of disability rights, disability theory is essential to thinking about how to solve problems, change cultural assumptions that lead to discrimination, and enable people to heal internalized ableism. I’m not sure that, when it comes to oppression, there really is a useful distinction to be made between thought and practice; after all, analyzing and critiquing oppressive norms like racism and ableism is part and parcel of creating change. For myself, reading disability theory has enabled me to move through discriminatory situations with a great deal more consciousness about what is actually going on (i.e. that it isn’t about me and “my problem”), and to therefore advocate for myself more effectively. When I can do so, not only do I help myself, but I also serve notice to people that the next disabled person who comes in the door may very well be prepared to do the same.

Perhaps the real issue isn’t the difference between theory and practice, but audience. For example, if academics are writing theory and it never goes beyond other academics and the pages of academic journals, then it cannot have an impact on ordinary people who need new frameworks in which to operate. This is a significant problem in academia. Except for my current graduate program, which is interdisciplinary and therefore oriented toward problem-solving, my experience in the field of humanities has been to be fired up with passion and outrage about the injustices of the world, only to hit the hard brick wall of the institution, which provides few opportunities for any sort of real-world practice. In fact, it was the presence of that wall that drove me out of academia for 25 years.

But my question about what constitutes activism goes far beyond questions of theory and practice into the mode of activism itself. For me, writing is my primary mode of activism, because it’s the way in which I communicate most effectively. It’s not the activism of talking to my legislators or organizing protests. It’s a quieter activism.

It’s the activism of replying to emails from parents, who ask about sensory issues, or about how to interpret their kids’ behavior, or about why certain language hurts.

It’s the activism of running the Autism and Empathy site, smashing stereotypes, and giving a place to voices that are all-too-often silenced in the popular media, in autism organizations, and in the scientific community.

It’s the activism of reflecting on my life, on my reading, and on my experience in a way that speaks to people who are just finding out that others feel as they do.

It’s the activism of building bridges with parents by letting people know that just as I need respect for my feelings and my process, so I will give them respect for theirs.

It’s the activism of creating a safe space on my blog, in which people who have never known safe spaces can express themselves without fear of being attacked for their perspectives.

It’s the activism of lifting up my voice and speaking out against murder, and abuse, and cultural violence against disabled people.

There are so many of us who cannot talk with our legislators, or organize protests, or do so many of the things that we tend of think of as activism. I am beginning to realize that defining activism is those ways is much too narrow. Of course, all those things are important. But they are not the only way to make change, and defining activism in those ways is to give in to ableist notions of what sort of action is worthwhile and what sort is not.

The fact is that it’s all activism. Every single piece of it.

Every disabled person who has the courage to ask for the accommodations they need at school or in the workplace is an activist.

Every disabled person who comes out of the closet and says, “This is who I am,” is an activist.

Every disabled person who works to defends his or her psyche against a steady onslaught of devaluation and dehumanizing messages is an activist.

Every disabled person who shares the words of another disabled person, and thereby helps to create a network of mutual support and pride, is an activist.

How could it be otherwise, when simply being disabled and loving our lives is a radical act?

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Homelessness is a Disability Issue

“Nearly all of the long-term homeless have tenuous family ties and some kind of disability, whether it is a drug or alcohol addiction, a mental illness, or a physical handicap.” — Dennis Culhane, 2010

I spend a fair amount of time these days talking with people who live on the street. I distribute bag lunches three times a week in San Lorenzo Park and on Pacific Avenue in Santa Cruz. I stop and chat with people, and I listen to their stories. People are getting to know me now, and they say hello to me at the drugstore and at the bus station and on the street. Some of them I consider friends; others are just folks I exchange a few words with; still others say very little at all.

The number of disabled people living on the street in Santa Cruz is staggering. Most of the people I talk to are disabled. Either I see their disabilities at first glance or I hear about them when people talk about their lives. The most obvious are the people with visible disabilities: people who use wheelchairs but can only move them by shuffling their feet, people who need wheelchairs but can’t afford them, people who use walkers and push chairs on which all of their belongings are piled, people who are blind but have no cane and no guide dog. Then there are the people who are mentally ill: the ones who talk to the voices they hear, the vets with PTSD, the men and women laboring under severe depression. And then there are the ones with invisible disabilities: the middle-aged man who stims and rocks and self-talks at the bus stop, the older fellow with leg and back injuries, the young man who understands everything but has trouble speaking in words. And of course, there are the alcoholics and the drug addicts, including the ones who line up at the methadone clinic.

When we talk about homelessness, we don’t often talk about the sheer numbers of disabled people living without shelter. And when we talk about disability, we don’t often talk about how many disabled people end up on the street. We don’t talk enough about the ways in which disability puts people at risk of homelessness and about the ways in which homelessness puts people at risk of disability. But think about the level of physical vulnerability involved — the lack of medical care, the lack of decent food, the sexual and physical assaults, the constant vigilance — and it’s not difficult to see how people become disabled on the street. If you didn’t have PTSD before homelessness, you’ll probably have it once you’ve become homeless. If you didn’t have an alcohol problem before you became homeless, you might acquire one just to be able to sleep. If you weren’t physically disabled before you became homeless, you might become so through assault or untended injury. And if you weren’t ill before you became homeless, you might easily become so through chronic lack of sleep.

In Santa Cruz, it is illegal to sleep outdoors between 11 pm and 8:30 am, and in the library at any time. How are people supposed to find their way out of homelessness if they can’t even sleep? It boggles the mind.

And how can anyone can say that all people need to do is to quit being so lazy and get a job? Fine. You want people to quit sleeping outdoors? Find people a job that accommodates their disabilities. Locate accessible housing. Get people the assistive devices they need. Help people hire a support staff. I’m sure that any one of the people I’ve spoken to would be only too happy to sign right up.

The need out there is so great. Our disabled brothers and sisters are crying out for justice.

References

Culhane, Dennis. “Five Myths About America’s Homeless.” The Washington Post, July 11, 2010. Accessed September 12, 2013. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/07/09/AR2010070902357.html.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Why So Many Fail to Understand Systemic Oppression

I was recently in a discussion about the ways in which people of color are disproportionately targeted by the police (think: stop-and-frisk, among other rights violations), disproportionately incarcerated, and disproportionately imprisoned for long stretches. As is often the case in these kinds of discussions, someone came blundering in with a “solution” — the “solution” being that people of color just need to be compliant with police officers and not do anything at all that could possibly be construed as suspicious or alarming. In other words, people of color simply had to act “normal” and all would be well.

I kept reading those words over and over, because I found them so shocking. It wasn’t just that the ideas were wrong — that they evinced an ignorance of racism and an idealized sense of control. It’s that they were based on an outlook that I once believed was grounded in fact: that society is “just” and that all I had to do to be safe was to do everything “right.”

That was a lifetime ago. At some point, I realized that there was no way to do it “right” because, in the eyes of the society in which I live, I am already seen as “wrong.” This assumption of wrongness is why marginalized people get the attention of the police, not to mention other authority figures, for driving while black, for walking while trans, for standing while disabled. We’re already considered “wrong” in the first place.

Some people’s bodies are themselves considered provoking. Not our intentions. Not our attitudes. Not our actions. OUR BODIES. To understand this very basic fact goes against the whole notion that the society one lives in is just — that the good are rewarded and that the guilty are punished. It’s deeply terrifying to realize how truly irrational people are when it comes to the arbitrary meanings they place on human bodies. It means that entire systems are based on completely arbitrary and irrational standards. It goes against the whole Western notion that humans are rational and enlightened beings.

It’s a very hard thing to wrap your mind around until it comes your way. And even when it does come your way, it’s still something that is difficult to face. This is one of the reasons that even people inside marginalized groups can fail to grasp the systemic injustices directed against their bodies. Or if they do grasp it, they can fail to understand the irrationality of the hatred directed toward other people’s bodies. So you find gay and lesbian people who are racist and transphobic, and you find people of color who are homophobic and ableist, and you find transgender people who are ageist and fatphobic, and you find disabled people who are misogynist and classist. Depending on who you talk to, you’ll find a multitude of permutations of all of these bigotries, including the horrifying specter of internalized hatred against one’s own body.

To realize that these valuations are simply arbitrary — that there is no good reason at all to suspect a body just for being a body — means to recognize that we are all at risk. Stigma is a moveable feast. It is mercilessly easy to move from a privileged category to a stigmatized category. Just ask anyone who has ever been diagnosed with a disability after living with the privileges of able-bodiedness, or anyone who has ever become fat after being thin, or anyone who has become old after a lifetime of looking youthful. The whole notion that the society is constructed along rational lines comes crashing down. And then you have to reconstruct your sense of how it works, piece by piece.

You’ll find other people who have woken up and found a new way of seeing. But you’ll never really believe again that the world you live in is just.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

The Sins Invalid Film: An Interview with Patty Berne and Leroy Moore

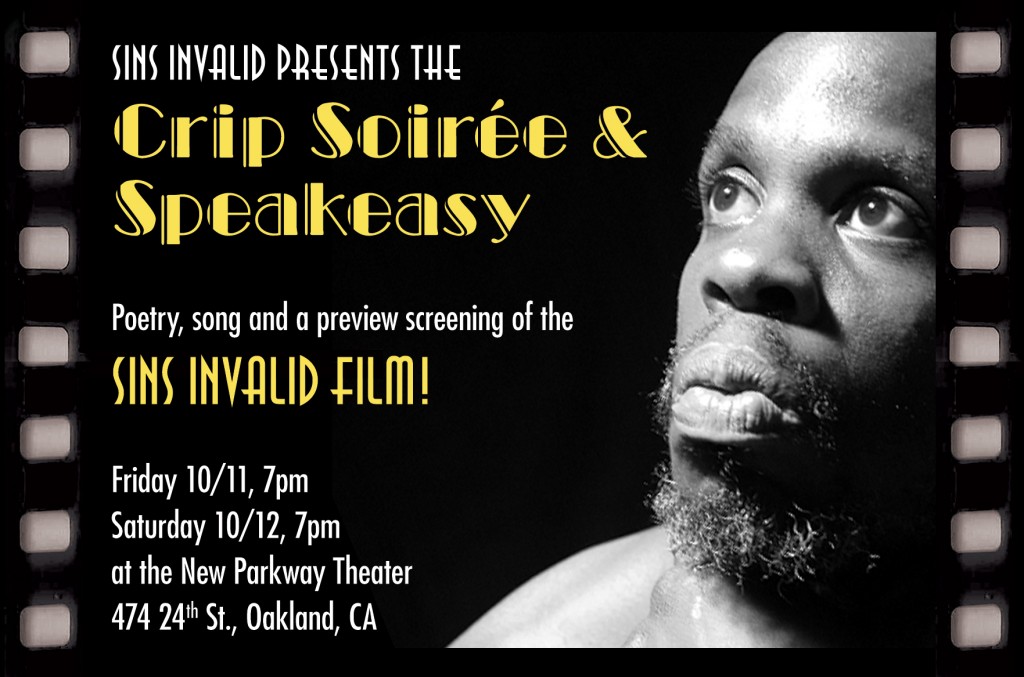

[The graphic consists of the face of a Leroy Moore looking upward and to the left. The left and right borders are drawn to look like the perforations in film negatives. Against a black background, the text reads: "Sins Invalid presents the Crip Soiree and Speakeasy. Poetry, song, and a preview of the Sins Invalid film! Friday 10/11, 7 pm, Saturday 10/12, 7 pm, 474 24th St., Oakland, CA."]

Sins Invalid is a performance project on disability and sexuality that makes central the work of queer artists, gender-variant artists, and artists of color. Over the past several years, Sins Invalid has been producing a film about its work. The Sins Invalid film will premiere in Osaka, Japan on September 14 and will be shown thereafter in venues around the US.

This past week, I interviewed two of the co-founders of Sins Invalid, Patty Berne and Leroy Moore, about the film, about their work, and about the ways in which Sins Invalid engages issues of disability, sexuality, and justice.

Rachel: What led you to create the Sins Invalid film?

Leroy: We wanted to get Sins‘ artistic and political vision and work beyond the Bay Area. We know that our community has grown nationally, even internationally, and while there’s nothing like a live performance, we wanted to make ourselves as accessible as possible for non-local community.

Patty: The power of the artists’ work really lays in the visual narratives as well as language. It’s important to see disabled bodies (however one defines that) actually embodying power and grace and sexual agency.

Leroy: There’s nothing like having full control of the context and the message both — and we are able to do that on stage and in many ways in film media as well.

Patty: We are being very thoughtful about where and how the film is shown, attempting to partner with community-based organizations to screen it. We are actually having our world premiere in Osaka Japan in a week!

Rachel: That’s so exciting! What will be the venue in Osaka? Where is the film being shown?

Patty: It will be shown as part of the Kansai Queer Film Festival at HEP Hall in Osaka. They invited me to attend and speak as well. They are interested in intersectionality and the potential for allegiance between those doing queer organizing and disability organizing. I’m specifically going to address relationships between gender justice and disability justice.

As a power chair user, I must admit to being very nervous about the ableist air transportation system. But I think it’s an amazing opportunity for disability justice frameworks to go international and for us to build relationship with queer folks with disabilities in Japan. And, it’s a particular honor for me, as I’m Japanese American. (My mother is from Kamakura and immigrated here in the 1940′s.)

Rachel: I’m glad you’re able to avail yourself of this opportunity. Intersectional discussions that include disability are crucial. As I watched the film, I found myself very interested in the process of how you put it together. When did you begin, and what was the process like as it unfolded?

Leroy: We began the film process in 2007 and have accumulated approximately 100 hours of footage.

Patty: As Leroy said earlier, we decided to document the work as a way to spread our vision and begin these conversations in broader sectors. Film has SUCH a broad reach. And as I said earlier, the visual narratives are as powerful as our language. But we had no idea what we were getting into really! I have so much respect for filmmakers! The medium is resource intensive and relatively unforgiving.

We’ve worked with 3 editors over the course of the 5 years, and finally really clicked with one in the last push toward completion.

Rachel: I’m so impressed both by the quality of the art depicted and by the film itself. It is all so beautifully done. Could you each speak to the ways in which the art of Sins Invalid serves the cause of disability justice, particularly in terms of disability and sexuality?

Patty: Thank you for appreciating the work! We live in a very visual age, where we are inundated, saturated by imagery. But most of that imagery reflects systems of oppression and the violence that supports it, slickly produced and packaged so that we consume it without reflecting on what narratives we are ingesting.

We decided to produce performance with high artistic merit because, as artists, that is important to us, but also because we are aware that disability imagery is perpetually used to reinforce our own oppression — charity programs like the MDA Telethon, the specter of the ghastly cripple as in David Lynch films, the tragic crip who serves the higher purpose through suicide as in Million Dollar Baby…

We need images of the truth — that we are powerful and complex and fucking HOT — not despite our disabilities but because of them!

In any movement, there is a need for artists to reflect the reality of the communities, and I think that’s what we’re doing. It’s also our responsibility to reflect the political imagination for what liberation could look like, so we seek to do that as well.

I think movements need a variety of formations — organizations who organize its base, think tanks and scholars and media, policy makers, cultural workers… And I like to think that Sins is doing that cultural work

We focus on disability and sexuality with in a disability justice framework specifically because sexuality is a human right, yet it is one of the most painful ways that we are dehumanized. We are neutered in the public eye (at least in this national context). We recognize our wholeness — including our lived embodied experience and our sexuality — and want to reflect that wholeness.

Leroy: I wanted to add that typically we see sexuality as something we do individually and privately, and we don’t usually see its impact on community. Sins breaks up the idea that sexuality is just an individual activity but brings sexuality into the conversation as a political issue to include as part of justice work. After all, it’s part of our oppression.

Rachel: Yes. One of the most powerful things about Sins Invalid is that it celebrates that disabled people have a lived experience of the body — that our bodies are not inert or inanimate. Given that human beings live in bodies, showing our lived experience is crucial for asserting our humanity.

With regard to justice work, what are the commonalities that you see in the struggle for social justice among marginalized peoples — particular among people of color, trans* and genderqueer people, disabled people, and queer folk — and how does Sins Invalid speak to these commonalities?

Patty: There are many commonalities and points of distinction. One of the primary commonalities is that a tactic of oppression used against all of us is that the oppression has been inscribed on our very skins — that our oppressions have been naturalized as a by-product of having a particular body — so that people think that what is difficult about being gender non-conforming, for example, is being in a non-conforming body, as opposed to being in a system of gender binary and heteronormativity. Or that what is difficult about being disabled is needing an accommodation, as opposed to living within ableism.

Another point of overlap is that our sexualities have been demonized and seen as vile or dangerous, and used as a way of engendering fear of us. Relatedly, our communities’ reproductive rights have been attacked through eugenic practices and programs.

All of the oppressed communities that you identified — communities of color, disability communities, trans/genderqueer communities, queer communities — we are all living within a white, able-bodied, heteronormative patriarchal capitalist context and struggle daily to live safely, with dignity. We each have struggles specific to our own experience of oppression, certainly, but the various systems of oppression reinforce each other and all manifest into all of our communities.

Leroy: And beyond a shared oppression, all of our communities have a rich culture — arts, music, poetry — and through our creation we can learn about each other and how we have each celebrated our own existences and spoken out against injustice. For example, there is a community of queer black women in the Blues that survived “isms” and created strategies for living and amplifying their artistic voice, and I think all communities can learn from that.

Rachel: I agree. One of the things that I appreciate about the work you do is that you go beyond critique into talking about how life can and must be. Along these lines, what kind of impact do you hope the film will have?

Patty: I think we are hoping for folks with disabilities who may not have thought about themselves as beautiful or sexy to see themselves in our work and to see their beauty. And for folks who may be functionally disabled but did not want to identify themselves as disabled due to stigma to perhaps feel a bit safer in rethinking the rigid line separating disabled from able-bodied. And for folks who love the work to move resources toward disabled artists!

And more deeply, to change the public debate about disability and sexuality so that it is a given that we have sexual agency, and that it is recognized that as people with disabilities we are also black and brown and queer and genderqueer and that we are not trading one identity for another. So that when we have a conversation about disability and sexuality, we are necessarily discussing our need for deinstitutionalization so that we can express our sexuality. So that when we discuss disability, we are necessarily addressing the incarceration of black men and the treatment of disabled prisoners. Does that make sense?

Rachel: Absolutely.

Patty: Our hope is that the film humanizes us — all of us.

Leroy: We hope that it will open doors of the heart and mind about what cultural work can look like, to go beyond identity politics alone to witness the diversity and strength of our communities. We hope that the film will be an educational tool for youth with disabilities, especially youth of color.

I hope that the film contributes to a cultural critique about people with disabilities and how we are represented in the media.

Patty: We are developing a study guide so that people can read articles or poems and have discussions in their own settings reflecting on the film and what it evokes for them.

Rachel: I hope that all of the work you’re doing will get people talking. Where will the film be screened, and where can people purchase a copy?

Leroy: We are trying to get into film festivals around the country and partnering with colleges and community based groups everywhere to get the film out initially. We are new members of New Day Films, who will be supporting our distribution. Pretty soon our film will be available for individual purchase at http://www.newday.com!

And in the Bay Area, folks should come out for our Crip Soiree and Speakeasy on October 11th and 12th at the New Parkway Theater in Oakland. You can get tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com/event/444189.

And if you are in Japan, go to the Kansai Queer Film Festival . Patty will be in Osaka screening the film and discussing our work on Sept. 14th! Sins goes international!

Patty: If anyone is interested in bringing the film to their campus or group, feel free to contact us at info@sinsinvalid.org. Or if you want to purchase an individual copy before New Day has it, drop us a line at info@sinsinvalid.org.

Rachel: Thank you both for taking the time to talk about Sins Invalid. Much success to you!

[Against a yellow background bordered by black lines with diamond designs at each corner, the text reads: "Sins Invalid celebrates the power of embodiment, disability and sexuality, by offering a vision of beauty that includes all bodies and communities.

[Against a yellow background bordered by black lines with diamond designs at each corner, the text reads: "Sins Invalid celebrates the power of embodiment, disability and sexuality, by offering a vision of beauty that includes all bodies and communities.

Come mingle, nibble and flirt at the Crip Soiree and Speakeasy, while artists Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Nomy Lamm, Maria Palacios, seeley quest and Leroy F. Moore, Jr. entice you with song and poetry following by a...

Preview screening of the Sins Invalid Film

7 pm on Friday, October 11th and Saturday, October 12th, 2013

at the Screening Room at the New Parkway Theater, 474 24th St. at Telegraph Ave., Oakland

Tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com/event/444189, $15-$100 sliding scale

ASL interpreted – Audio Description – Wheelchair accessible

Please refrain from using scented products

Please note: Film contains explicit content.

www.sinsinvalid.org | info@sinsinvalid.org | 510.689.7198

Sins Invalid is a fiscally sponsored project of Dancers' Group. We are grateful for the generous support of the Aepoch Fund, the Left Tilt Fund, the San Francisco Arts Commission, the Carpenter Foundation, the Horizons Foundation and the Fairy Godfathers Fun, Astraea Foundation, Community Foundation Boulder, Zellerbach Family Foundation and the Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation, the Dancer's Group New Stages for Dance Program, the Brown Boi Project, and each of our FABULOUS INDIVIDUAL DONORS AND KICKSTARTER BACKERS!!”]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Getting Beyond Etc. — A Short Response to Andrea Smith’s The Problem with “Privilege”

There are many good things to say about Andrea Smith’s piece The Problem with “Privilege.” She is absolutely right that to effect systemic change, we must get past the point of self-reflection on privilege, confessions of privilege, and ranking of privilege. She is right that we have to start working to dismantle privilege in all of the spaces we create and in all of the systems in which we are complicit.

But I have a serious problem with an otherwise excellent intersectional analysis: It mentions disability precisely once.

I begin articles like this one with great hope that disability will be integrated into the analysis — only to find, with great disappointment, that disability seems to merit a mere mention (if that). It’s a depressingly recurrent pattern. It often leaves me wondering whether to engage the author’s other arguments, or to simply leave the discussion, secure in the knowledge that, once again, I have not really been invited in.

One of the early warning signs of trouble ahead is Smith’s listing of oppressions under the “gender/race/sexuality/class/etc.” heading (Smith 2013). I cannot exaggerate how much I detest listing oppressions in this way. My friends and I are not an “etc.” My friends and I are disabled. When Smith does not explicitly incorporate this category into an analysis of the colonized subject, she has just done the very same thing that she is arguing against: constituting herself against an imagined Other.

The subject of which she speaks is not disabled. Like the White subject who has to be “educated” about race, the subjects of Smith’s piece have to “educate ourselves on issues in which our politics and praxis were particularly problematic: disability, anti-Black racism, settler colonialism, Zionism and anti-Arab racism, transphobia, and many others” (Smith 2013). But to whom does the word “ourselves” refer? Who is inside that group? Who is outside? By implication, most of the people on the outside are the ones consigned to a handy category called “etc.” about whom we have to “educate ourselves.”

Despite the us/them division thus evoked, we folks in the “etc.” category are already here, hidden in plain sight.

Please start talking about us as though we are you. Because we are.

Please start talking about us as though we have struggled for generations inside of our own civil rights movements. Because we have.

Please start talking about us as though our oppression winds its way through every other oppression under which people labor. Because it does.

And please start talking about us as though we merit the same attention as any other group of dehumanized, Othered folk. Because we do.

References

Smith, Andrea. “The Problem with “Privilege.” Andrea 366. August 14, 2013. Accessed August 29, 2013. http://andrea366.wordpress.com/2013/08/14/the-problem-with-privilege-by-andrea-smith/.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Why This Disabled Woman No Longer Identifies as a Feminist

I became a feminist in 1972. Back then, it was still called “Women’s Lib,” sometimes by other feminists (cringe), and sometimes by anti-feminists (usually with a dismissive sneer). My father described me as being on “a Women’s Lib kick” for wanting to stay unmarried into my 20s, go away to college, and work. Judging by my aims at the time, you can see how early this feminism was.

It pains me to say that I no longer identify as a feminist.

It’s not that I’ve left behind the principles of feminism. Not at all. I’m not dismissing feminism or the feminist movement. I’m not anti-feminist. I’m deeply supportive of the principles of feminism and I will continue to work on behalf of them. But it’s not going to happen inside the movement.

Inside feminism, I’m marginalized at best. Usually, I’m invisible. I can’t stay, because staying is painful.

It took me awhile to figure this out. I was involved in a lot of different kinds of feminist work: agitating and getting in the trenches against rape and domestic violence, doing work in support of women of color and homeless women, campaigning for reproductive choice… you get the idea. I raised my genderqueer kid, who identified as female in childhood, in an all-women’s and girls’ dojo and taught that kid to kick the ass of anyone who messed with them.

But all along, something was missing. Some of it was obvious from the beginning: lots of foregrounding of whiteness, lots of talk about middle-class educated women, lots of talk about being competitive and ambitious and accomplished. I could never understand it. Down at the local Safeway, I’d talk with homeless women panhandling with their kids (sometimes white women and sometimes women of color), and when I’d get home, I’d find letters in the mail from feminist organizations about how middle-class educated white women just couldn’t seem to find their ways into the executive suite. I found it, well, obnoxious, and I used to send off letters telling people so. And much of the time, the response was along the lines of, “What you have to say is SO important. We’re getting there! Just you wait and see!”

The last time I wrote one of those letters was around 1993. For some sense of how far we haven’t come, take a look at Syreeta’s What we don’t talk about when we talk about Mommy Wars and Jessie-Lane Metz’s Ally-Phobia: On the Trayvon Martin Ruling, White Feminism, and the Worst of Best Intentions, both published this month.

So many feminists are still having trouble talking about racism. But truthfully, I’d settle for feminists talking about disability really, really poorly because, at this point, so few feminists consider disability at all.

Now before you jump in and say, “Oh, no, no, Rachel. I’m a feminist and I’M NOT LIKE THAT,” rest assured that I’m aware of feminists who are taking intersectionality seriously. I see you there. I do. But unfortunately, you are way too few and far between.

I spend a lot of time reading intersectional analyses. I used to go into them with a certain amount of glee, thinking, “All right! Finally! Disability is on the table!” I am no longer so naive. When feminism was just about gender, it was bad enough. Single-issue politics have never made a lot of sense to me. How can an experience of gender be divorced from an experience of anything else that comes with being in a human body? I understand the need to focus on gender issues, but that has to be reflected through a number of other prisms. Otherwise, you default to the culturally invisible prism: cis-gendered, able-bodied, normatively sized, middle-class, white Anglo-Saxon Protestant women. I am so done with that.

But what really, really drives me to bitter tears and raging inside my head is when people are all INTERSECTIONALITY FOREVER and WE’RE NOT SINGLE ISSUE FEMINISTS and WE’RE INCLUSIVE OF EVERYBODY and they chronically leave out disability from the analysis. And then when I mention the omission, I am met with silence (on a good day) and hostility (on a needlessly crappy one). The result is only more bitter tears and more raging inside my head.

It’s not that we have to all talk about all oppressions all the time. That would make it impossible to write an article or have a conversation and stay on point. But so often, I see the following pattern:

1. Writer composes an intersectional analysis that brings together race, class, and gender.

Okay. We’re good, though I’m still wishing that the analysis will be expanded.

2. Writer mentions that she is aware of multiple other forms of oppression but simply can’t speak to them all without losing the focus of the piece.

Fine. I respect any writer’s need to stay on point.

3. Writer mentions those multiple other forms of oppression, just to show that she is not ignoring other oppressed people. This is how so many of these lists go:

They almost always include sexual orientation.

On a good day, they include transgender people, people of non-normative sizes, and ethnic and religious minorities.

Once in a blue moon, the word genderqueer or non-binary or intersex appears.

If I’m really lucky, I’ll see the word disability. Usually, it disappears into the mist of phrases like “and all other oppressions.”

I get why this is happening. Feminism doesn’t know WTF to do with disability, because disability throws a huge monkey wrench into the gears of the feminist notion that we’re supposed to be strong, independent, and accomplished beings, healthy and full of power. Great! What about the women with disabilities for whom going to the grocery store takes a profound amount of energy? What about women whose bodies are weak? What about women who rely upon others for assistance with basic tasks? What about women in constant pain? What about women incarcerated in nursing homes and mental institutions? Where do they fit into your dream of the strong, independent, accomplished woman?

They don’t. WE DON’T.

What so many able-bodied feminists don’t get is how profound an experience disability is. I’m not just talking about a profound physical experience. I’m talking about a profound social and political experience. I venture out and I feel like I’m in a separate world, divided from “normal” people by a thin but unmistakeable membrane. In my very friendly and diverse city, I look out and see people of different races and ethnicities walking together on the sidewalk, or shopping, or having lunch. But when I see disabled people, they are usually walking or rolling alone. And if they’re not alone, they’re with a support person or a family member. I rarely see wheelchair users chatting it up with people who walk on two legs. I rarely see cognitively or intellectually disabled people integrated into social settings with nondisabled people. I’m painfully aware of how many people are fine with me as long as I can keep up with their able-bodied standards, and much less fine with me when I actually need something.

So many of you really have no idea of how rampant the discrimination is. You have no idea that disabled women are routinely denied fertility treatments and can be sterilized without their consent. You have no idea that disabled people are at very high risk of losing custody of their children. You have no idea that women with disabilities experience a much higher rate of domestic violence than nondisabled women or that the assault rate for adults with developmental disabilities is 4 to 10 times higher than for people without developmental disabilities. You have no idea that over 25% of people with disabilities live in poverty. You have no idea that the ADA hasn’t solved everything and that disabled people are still kept out of public places, still face discrimination in employment, and are still treated like second-class citizens undeserving of rights.

So many of you aren’t even thinking about disabled people when you casually throw words into your social justice rhetoric like crazy, insane, moronic, idiotic, and lame to describe ideas you do not like.

So many of you have no idea that the civil rights of disabled people are being violated every damned day only because they are disabled.

So many of you have no idea that disability is a civil rights issue AT ALL.

I’ve had people tell me that I should stay inside feminism and fight the good fight. I’ve been told that nothing will change if I leave. I’ve been told that I’m just giving up too soon (although I have trouble believing that 40 years is too soon). But this kind of logic makes no sense to me. The message is, “Stay in a movement in which you’re invisible, and keep talking about how you’re invisible, so that maybe someday, you won’t be invisible.” But that just turns the entire issue on its head. It becomes all about me and what I’m doing, and not about feminism and what it’s doing.

I don’t need to solve the ableism in the movement. It’s not my job. It’s the job of my nondisabled sisters who haven’t begun to address their own their own fears and their own omissions.

I shouldn’t have to remain inside a movement in which I’m nearly invisible as the price of getting people to listen to me. I’m still writing. I’m still speaking up. I haven’t gone anywhere.

The disability rights movement is decades old. Educate yourselves. Talk to us. Think about us as your audience. Stop ignoring us. That’s all I ask.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

How to Leave Disability Rights Out of Your Political Analysis

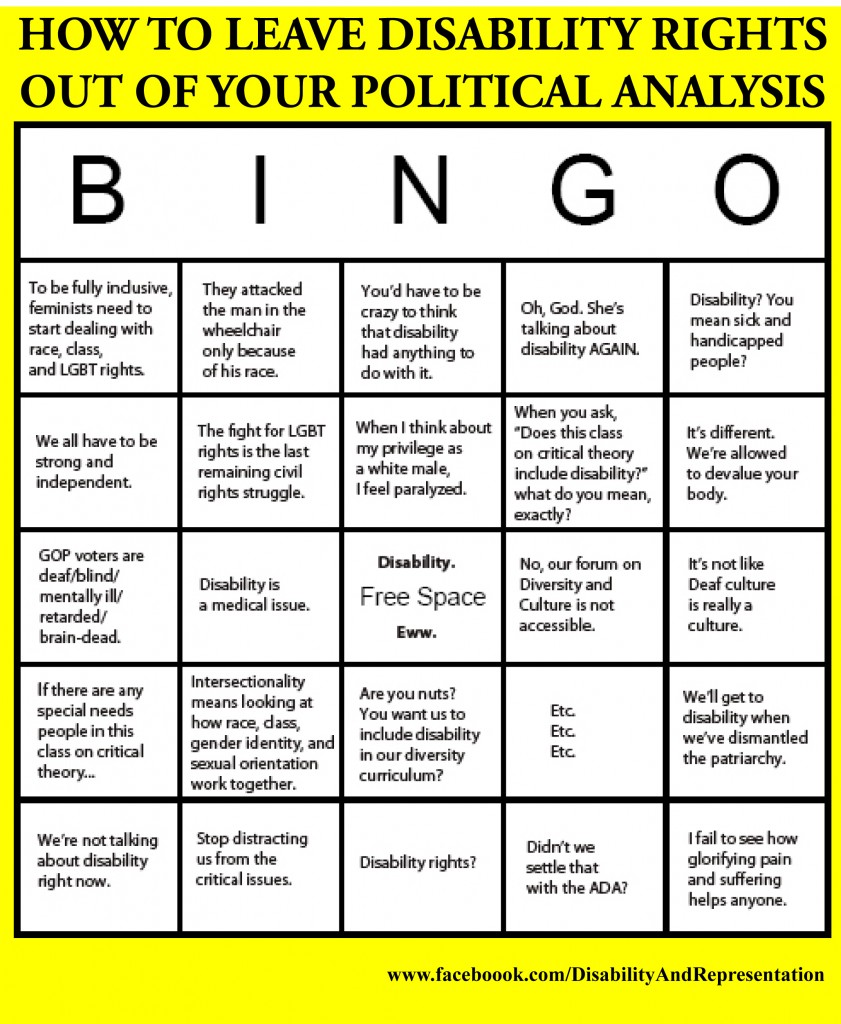

[The graphic is a Bingo card with 25 squares.

Title: How to Leave Disability Rights Out of Your Political Analysis

Top row:To be fully inclusive, feminists need to start dealing with race, class, and LGBT rights.

They attacked the man in the wheelchair only because of his race.

You'd have to be crazy to think that disability had anything to do with it.

Oh, God. She's talking about disability AGAIN.

Disability? You mean sick and handicapped people?

Second row: We all have to be strong and independent.

The fight for LGBT rights is the last remaining civil rights struggle.

When I think about my privilege as a white male, I feel paralyzed.

When you ask, “Does this class on critical theory include disability?” what do you mean, exactly?

It's different. We're allowed to devalue your body.

Third row: GOP voters are blind/deaf/mentally ill/retarded/brain-dead.

Disability is a medical issue.

Free Space: Disability. Eww.

No, our forum on Diversity and Culture is not accessible.

It's not like Deaf culture is really a culture.

Fourth row: If there are any special needs people in this class on critical theory...

Intersectionality means looking at how race, class, gender identity, and sexual orientation work together.

Are you nuts? You want us to include disability in our diversity curriculum?

Etc. Etc. Etc.

We'll get to disability when we've dismantled the patriarchy.

Last row: We're not talking about disability right now.

Stop distracting us from the critical issues.

Disability rights?

Didn't we settle that with the ADA?

I fail to see how glorifying pain and suffering helps anyone.

The text below the graphic reads www.facebook.com/DisabilityAndRepresentation.]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

A Rant to My Fellow Activists Who Do Anti-Oppression Work and Ignore Disability

Dear Activists Who Wax Eloquently About The Importance Of Intersectionality In Anti-Oppression Work:

I need to make a request. I’ll try to keep it brief and I’ll do my best to be clear about exactly what I mean.

PLEASE STOP FUCKING IGNORING DISABILITY.

I’ve noticed that many of you complain loudly and vehemently that feminism doesn’t do intersectionality right because it leaves out race, class, LGBT issues, genderqueer issues, religion, ethnicity, and body size. I agree. I completely agree. It’s why I left feminism in disgust some time ago. So imagine my utter fucking surprise when I notice that, oh hell, there is no room for me to agree at all because, as a disabled woman, I haven’t even been invited into the discussion.

I mean, really. It’s provoking to watch you call out feminists for not doing intersectionality right while you leave disabled people out of it altogether. While you keep chanting “race, class, gender” over and over, congratulating yourselves on how inclusive you’re being, you’re leaving out one-fifth of the population.

Disability winds through every other form of oppression. There are disabled people of color, disabled working class people, disabled poor people (lots), disabled LGBT people, disabled genderqueer people, disabled fat people, disabled religious people, disabled people of every ethnicity, and disabled people who experience every form of oppression that human beings can perpetrate. I know the thought that you could become one of us in a millisecond scares the absolute living fuck out of you, but seriously, deal with your fears already because they are not helping us. Start grokking the fact that disabled people are being assaulted, killed, institutionalized, and otherwise having their civil rights violated every goddamned day.

Because in case you haven’t gotten the memo, disability is a civil rights issue.

When people have their children taken away because they’re disabled, it’s a civil rights issue. When people are refused entrance into a restaurant or a theatre or a public park, it’s a civil rights issue. When people are counseled to die rather than live, it’s a civil rights issue. When people are consigned to poverty because of the ways their bodies look and function, it’s a civil rights issue. When people are assaulted, spit on, and killed because they’re disabled, it’s a civil rights issue. When people live in isolation even within communities that talk about oppression and social justice, it’s a civil rights issue.

Every time you fail to acknowledge our presence, it only increase our invisibility. So really, how the hell are we disabled people supposed to join you in doing anti-oppression work if you keep treating us like the embarrassing relative no one talks about?

Allies have one another’s backs. No way in hell am I saying, “I’m your ally, but when it comes time for you to fight for me, I’m on my own.”

Fair is fair.

Reciprocity forever.

In solidarity,

Rachel

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Updated Post: Just How Far We Are From Equality: The San Diego Museum of Man’s Access/ABILITY Exhibit

I’ve updated this post after receiving an email and a comment from Grant Barrett, the Marketing Manager at the San Diego Museum of Man. Apparently, the disability exhibit is on the first floor and is fully accessible; moreover, the city of San Diego — not the museum — is responsible for the elevator repair. The second floor, which holds other exhibits, is not accessible at this time. Mr. Barrett writes:

Rachel, thanks so much for writing about the exhibit.

Unfortunately, you got an essential fact wrong: the access/ABILITY exhibit is totally accessible to people with disabilities. It’s on the first floor, and we have ramps and wide navigation paths everywhere we need them on that level.

We put the elevator notice on that page because we know that our disabled guests will want to see more than that one exhibit. The notice is also on the front page of the website and we announce it with signs at admissions.

The elevator repair, by the way, is beyond our control. The City of San Diego owns our buildings and maintains our elevators. We have no say as to when they will repair them or how long it will take. We’re hoping that the repairs will take much less time than predicted.

Thanks for being considerate of all of our visitors and keep up your good works.

In the light of Mr. Barrett’s email and comment, of course, I’ve corrected the post. My main points, however, still stand: any inaccessibility is a civil rights violation, and the presence of the exhibit itself reflects the basic segregation and inequality with which disabled people live.

—

I know that our society, by and large, does not yet see disability as a civil rights issue. I know that when people see stairs but no elevator, most of them don’t realize they’re looking at a civil rights violation. I know that most people don’t even blink when they see a sign that says that people with disabilities have to enter through the back door.

But every now and then, I’m surprised by how far behind the curve we are. Case in point: The San Diego Museum of Man has an exhibit called access/ABILITY in which you can allegedly “learn about how people with disabilities navigate the world!” (Exclamation point not mine.)

How does one become thus enlightened? Well, all you have to do is to “Learn phrases in American Sign Language, type your name in Braille, try a hand-pedaled bike and take part in a multi-sensory City Walk!” (Again, exclamation point not mine.) Because that’s what it takes to understand how disabled people live. Just go to a museum.

And of course, it is sure to “inspire.” It always, always has to “inspire.” Because really, that’s how disabled people navigate the world. Inspiringly.

And then — and hold on for this one — the exhibit is currently not accessible to people with disabilities.the entire second floor is inaccessible to people with disabilities. Yes: in a museum with an exhibit showing how disabled people “navigate the world,” disabled people cannot navigate up to the second floor to see any of the exhibits there. I’m not kidding. The website reads:

Our elevator will be out of service June 24 through August 2. If you require an elevator, you will be unable to visit the second floor exhibits. We apologize for the inconvenience.

Of course, these three sentences are not without irony. After all, they say more about how disabled people navigate the world than a museum exhibit ever could. Not only is the exhibit second floor inaccessible, but the lack of an elevator is described as an “inconvenience” rather than as a civil rights violation. For those just joining us, that’s like calling a sign that says, “No blacks or Jews allowed” an inconvenience rather than a civil rights violation.

The very existence of this kind of exhibit (are we still exotic animals to be exhibited?) speaks volumes about the inequality and social segregation of people with disabilities. Volumes. If we people with disabilities were actually integrated into society, people would have a pretty stellar notion of how we navigate the world. But when we’re set apart, we become curiosities.

As far as I’m concerned, this kind of exhibit is simply the 21st-century equivalent of a freak show. The fact that such things still exist is evidence of how very far we have to go.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg