Why So Many Fail to Understand Systemic Oppression

I was recently in a discussion about the ways in which people of color are disproportionately targeted by the police (think: stop-and-frisk, among other rights violations), disproportionately incarcerated, and disproportionately imprisoned for long stretches. As is often the case in these kinds of discussions, someone came blundering in with a “solution” — the “solution” being that people of color just need to be compliant with police officers and not do anything at all that could possibly be construed as suspicious or alarming. In other words, people of color simply had to act “normal” and all would be well.

I kept reading those words over and over, because I found them so shocking. It wasn’t just that the ideas were wrong — that they evinced an ignorance of racism and an idealized sense of control. It’s that they were based on an outlook that I once believed was grounded in fact: that society is “just” and that all I had to do to be safe was to do everything “right.”

That was a lifetime ago. At some point, I realized that there was no way to do it “right” because, in the eyes of the society in which I live, I am already seen as “wrong.” This assumption of wrongness is why marginalized people get the attention of the police, not to mention other authority figures, for driving while black, for walking while trans, for standing while disabled. We’re already considered “wrong” in the first place.

Some people’s bodies are themselves considered provoking. Not our intentions. Not our attitudes. Not our actions. OUR BODIES. To understand this very basic fact goes against the whole notion that the society one lives in is just — that the good are rewarded and that the guilty are punished. It’s deeply terrifying to realize how truly irrational people are when it comes to the arbitrary meanings they place on human bodies. It means that entire systems are based on completely arbitrary and irrational standards. It goes against the whole Western notion that humans are rational and enlightened beings.

It’s a very hard thing to wrap your mind around until it comes your way. And even when it does come your way, it’s still something that is difficult to face. This is one of the reasons that even people inside marginalized groups can fail to grasp the systemic injustices directed against their bodies. Or if they do grasp it, they can fail to understand the irrationality of the hatred directed toward other people’s bodies. So you find gay and lesbian people who are racist and transphobic, and you find people of color who are homophobic and ableist, and you find transgender people who are ageist and fatphobic, and you find disabled people who are misogynist and classist. Depending on who you talk to, you’ll find a multitude of permutations of all of these bigotries, including the horrifying specter of internalized hatred against one’s own body.

To realize that these valuations are simply arbitrary — that there is no good reason at all to suspect a body just for being a body — means to recognize that we are all at risk. Stigma is a moveable feast. It is mercilessly easy to move from a privileged category to a stigmatized category. Just ask anyone who has ever been diagnosed with a disability after living with the privileges of able-bodiedness, or anyone who has ever become fat after being thin, or anyone who has become old after a lifetime of looking youthful. The whole notion that the society is constructed along rational lines comes crashing down. And then you have to reconstruct your sense of how it works, piece by piece.

You’ll find other people who have woken up and found a new way of seeing. But you’ll never really believe again that the world you live in is just.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

The Sins Invalid Film: An Interview with Patty Berne and Leroy Moore

[The graphic consists of the face of a Leroy Moore looking upward and to the left. The left and right borders are drawn to look like the perforations in film negatives. Against a black background, the text reads: "Sins Invalid presents the Crip Soiree and Speakeasy. Poetry, song, and a preview of the Sins Invalid film! Friday 10/11, 7 pm, Saturday 10/12, 7 pm, 474 24th St., Oakland, CA."]

Sins Invalid is a performance project on disability and sexuality that makes central the work of queer artists, gender-variant artists, and artists of color. Over the past several years, Sins Invalid has been producing a film about its work. The Sins Invalid film will premiere in Osaka, Japan on September 14 and will be shown thereafter in venues around the US.

This past week, I interviewed two of the co-founders of Sins Invalid, Patty Berne and Leroy Moore, about the film, about their work, and about the ways in which Sins Invalid engages issues of disability, sexuality, and justice.

Rachel: What led you to create the Sins Invalid film?

Leroy: We wanted to get Sins‘ artistic and political vision and work beyond the Bay Area. We know that our community has grown nationally, even internationally, and while there’s nothing like a live performance, we wanted to make ourselves as accessible as possible for non-local community.

Patty: The power of the artists’ work really lays in the visual narratives as well as language. It’s important to see disabled bodies (however one defines that) actually embodying power and grace and sexual agency.

Leroy: There’s nothing like having full control of the context and the message both — and we are able to do that on stage and in many ways in film media as well.

Patty: We are being very thoughtful about where and how the film is shown, attempting to partner with community-based organizations to screen it. We are actually having our world premiere in Osaka Japan in a week!

Rachel: That’s so exciting! What will be the venue in Osaka? Where is the film being shown?

Patty: It will be shown as part of the Kansai Queer Film Festival at HEP Hall in Osaka. They invited me to attend and speak as well. They are interested in intersectionality and the potential for allegiance between those doing queer organizing and disability organizing. I’m specifically going to address relationships between gender justice and disability justice.

As a power chair user, I must admit to being very nervous about the ableist air transportation system. But I think it’s an amazing opportunity for disability justice frameworks to go international and for us to build relationship with queer folks with disabilities in Japan. And, it’s a particular honor for me, as I’m Japanese American. (My mother is from Kamakura and immigrated here in the 1940′s.)

Rachel: I’m glad you’re able to avail yourself of this opportunity. Intersectional discussions that include disability are crucial. As I watched the film, I found myself very interested in the process of how you put it together. When did you begin, and what was the process like as it unfolded?

Leroy: We began the film process in 2007 and have accumulated approximately 100 hours of footage.

Patty: As Leroy said earlier, we decided to document the work as a way to spread our vision and begin these conversations in broader sectors. Film has SUCH a broad reach. And as I said earlier, the visual narratives are as powerful as our language. But we had no idea what we were getting into really! I have so much respect for filmmakers! The medium is resource intensive and relatively unforgiving.

We’ve worked with 3 editors over the course of the 5 years, and finally really clicked with one in the last push toward completion.

Rachel: I’m so impressed both by the quality of the art depicted and by the film itself. It is all so beautifully done. Could you each speak to the ways in which the art of Sins Invalid serves the cause of disability justice, particularly in terms of disability and sexuality?

Patty: Thank you for appreciating the work! We live in a very visual age, where we are inundated, saturated by imagery. But most of that imagery reflects systems of oppression and the violence that supports it, slickly produced and packaged so that we consume it without reflecting on what narratives we are ingesting.

We decided to produce performance with high artistic merit because, as artists, that is important to us, but also because we are aware that disability imagery is perpetually used to reinforce our own oppression — charity programs like the MDA Telethon, the specter of the ghastly cripple as in David Lynch films, the tragic crip who serves the higher purpose through suicide as in Million Dollar Baby…

We need images of the truth — that we are powerful and complex and fucking HOT — not despite our disabilities but because of them!

In any movement, there is a need for artists to reflect the reality of the communities, and I think that’s what we’re doing. It’s also our responsibility to reflect the political imagination for what liberation could look like, so we seek to do that as well.

I think movements need a variety of formations — organizations who organize its base, think tanks and scholars and media, policy makers, cultural workers… And I like to think that Sins is doing that cultural work

We focus on disability and sexuality with in a disability justice framework specifically because sexuality is a human right, yet it is one of the most painful ways that we are dehumanized. We are neutered in the public eye (at least in this national context). We recognize our wholeness — including our lived embodied experience and our sexuality — and want to reflect that wholeness.

Leroy: I wanted to add that typically we see sexuality as something we do individually and privately, and we don’t usually see its impact on community. Sins breaks up the idea that sexuality is just an individual activity but brings sexuality into the conversation as a political issue to include as part of justice work. After all, it’s part of our oppression.

Rachel: Yes. One of the most powerful things about Sins Invalid is that it celebrates that disabled people have a lived experience of the body — that our bodies are not inert or inanimate. Given that human beings live in bodies, showing our lived experience is crucial for asserting our humanity.

With regard to justice work, what are the commonalities that you see in the struggle for social justice among marginalized peoples — particular among people of color, trans* and genderqueer people, disabled people, and queer folk — and how does Sins Invalid speak to these commonalities?

Patty: There are many commonalities and points of distinction. One of the primary commonalities is that a tactic of oppression used against all of us is that the oppression has been inscribed on our very skins — that our oppressions have been naturalized as a by-product of having a particular body — so that people think that what is difficult about being gender non-conforming, for example, is being in a non-conforming body, as opposed to being in a system of gender binary and heteronormativity. Or that what is difficult about being disabled is needing an accommodation, as opposed to living within ableism.

Another point of overlap is that our sexualities have been demonized and seen as vile or dangerous, and used as a way of engendering fear of us. Relatedly, our communities’ reproductive rights have been attacked through eugenic practices and programs.

All of the oppressed communities that you identified — communities of color, disability communities, trans/genderqueer communities, queer communities — we are all living within a white, able-bodied, heteronormative patriarchal capitalist context and struggle daily to live safely, with dignity. We each have struggles specific to our own experience of oppression, certainly, but the various systems of oppression reinforce each other and all manifest into all of our communities.

Leroy: And beyond a shared oppression, all of our communities have a rich culture — arts, music, poetry — and through our creation we can learn about each other and how we have each celebrated our own existences and spoken out against injustice. For example, there is a community of queer black women in the Blues that survived “isms” and created strategies for living and amplifying their artistic voice, and I think all communities can learn from that.

Rachel: I agree. One of the things that I appreciate about the work you do is that you go beyond critique into talking about how life can and must be. Along these lines, what kind of impact do you hope the film will have?

Patty: I think we are hoping for folks with disabilities who may not have thought about themselves as beautiful or sexy to see themselves in our work and to see their beauty. And for folks who may be functionally disabled but did not want to identify themselves as disabled due to stigma to perhaps feel a bit safer in rethinking the rigid line separating disabled from able-bodied. And for folks who love the work to move resources toward disabled artists!

And more deeply, to change the public debate about disability and sexuality so that it is a given that we have sexual agency, and that it is recognized that as people with disabilities we are also black and brown and queer and genderqueer and that we are not trading one identity for another. So that when we have a conversation about disability and sexuality, we are necessarily discussing our need for deinstitutionalization so that we can express our sexuality. So that when we discuss disability, we are necessarily addressing the incarceration of black men and the treatment of disabled prisoners. Does that make sense?

Rachel: Absolutely.

Patty: Our hope is that the film humanizes us — all of us.

Leroy: We hope that it will open doors of the heart and mind about what cultural work can look like, to go beyond identity politics alone to witness the diversity and strength of our communities. We hope that the film will be an educational tool for youth with disabilities, especially youth of color.

I hope that the film contributes to a cultural critique about people with disabilities and how we are represented in the media.

Patty: We are developing a study guide so that people can read articles or poems and have discussions in their own settings reflecting on the film and what it evokes for them.

Rachel: I hope that all of the work you’re doing will get people talking. Where will the film be screened, and where can people purchase a copy?

Leroy: We are trying to get into film festivals around the country and partnering with colleges and community based groups everywhere to get the film out initially. We are new members of New Day Films, who will be supporting our distribution. Pretty soon our film will be available for individual purchase at http://www.newday.com!

And in the Bay Area, folks should come out for our Crip Soiree and Speakeasy on October 11th and 12th at the New Parkway Theater in Oakland. You can get tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com/event/444189.

And if you are in Japan, go to the Kansai Queer Film Festival . Patty will be in Osaka screening the film and discussing our work on Sept. 14th! Sins goes international!

Patty: If anyone is interested in bringing the film to their campus or group, feel free to contact us at info@sinsinvalid.org. Or if you want to purchase an individual copy before New Day has it, drop us a line at info@sinsinvalid.org.

Rachel: Thank you both for taking the time to talk about Sins Invalid. Much success to you!

[Against a yellow background bordered by black lines with diamond designs at each corner, the text reads: "Sins Invalid celebrates the power of embodiment, disability and sexuality, by offering a vision of beauty that includes all bodies and communities.

[Against a yellow background bordered by black lines with diamond designs at each corner, the text reads: "Sins Invalid celebrates the power of embodiment, disability and sexuality, by offering a vision of beauty that includes all bodies and communities.

Come mingle, nibble and flirt at the Crip Soiree and Speakeasy, while artists Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Nomy Lamm, Maria Palacios, seeley quest and Leroy F. Moore, Jr. entice you with song and poetry following by a...

Preview screening of the Sins Invalid Film

7 pm on Friday, October 11th and Saturday, October 12th, 2013

at the Screening Room at the New Parkway Theater, 474 24th St. at Telegraph Ave., Oakland

Tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com/event/444189, $15-$100 sliding scale

ASL interpreted – Audio Description – Wheelchair accessible

Please refrain from using scented products

Please note: Film contains explicit content.

www.sinsinvalid.org | info@sinsinvalid.org | 510.689.7198

Sins Invalid is a fiscally sponsored project of Dancers' Group. We are grateful for the generous support of the Aepoch Fund, the Left Tilt Fund, the San Francisco Arts Commission, the Carpenter Foundation, the Horizons Foundation and the Fairy Godfathers Fun, Astraea Foundation, Community Foundation Boulder, Zellerbach Family Foundation and the Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation, the Dancer's Group New Stages for Dance Program, the Brown Boi Project, and each of our FABULOUS INDIVIDUAL DONORS AND KICKSTARTER BACKERS!!”]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Getting Beyond Etc. — A Short Response to Andrea Smith’s The Problem with “Privilege”

There are many good things to say about Andrea Smith’s piece The Problem with “Privilege.” She is absolutely right that to effect systemic change, we must get past the point of self-reflection on privilege, confessions of privilege, and ranking of privilege. She is right that we have to start working to dismantle privilege in all of the spaces we create and in all of the systems in which we are complicit.

But I have a serious problem with an otherwise excellent intersectional analysis: It mentions disability precisely once.

I begin articles like this one with great hope that disability will be integrated into the analysis — only to find, with great disappointment, that disability seems to merit a mere mention (if that). It’s a depressingly recurrent pattern. It often leaves me wondering whether to engage the author’s other arguments, or to simply leave the discussion, secure in the knowledge that, once again, I have not really been invited in.

One of the early warning signs of trouble ahead is Smith’s listing of oppressions under the “gender/race/sexuality/class/etc.” heading (Smith 2013). I cannot exaggerate how much I detest listing oppressions in this way. My friends and I are not an “etc.” My friends and I are disabled. When Smith does not explicitly incorporate this category into an analysis of the colonized subject, she has just done the very same thing that she is arguing against: constituting herself against an imagined Other.

The subject of which she speaks is not disabled. Like the White subject who has to be “educated” about race, the subjects of Smith’s piece have to “educate ourselves on issues in which our politics and praxis were particularly problematic: disability, anti-Black racism, settler colonialism, Zionism and anti-Arab racism, transphobia, and many others” (Smith 2013). But to whom does the word “ourselves” refer? Who is inside that group? Who is outside? By implication, most of the people on the outside are the ones consigned to a handy category called “etc.” about whom we have to “educate ourselves.”

Despite the us/them division thus evoked, we folks in the “etc.” category are already here, hidden in plain sight.

Please start talking about us as though we are you. Because we are.

Please start talking about us as though we have struggled for generations inside of our own civil rights movements. Because we have.

Please start talking about us as though our oppression winds its way through every other oppression under which people labor. Because it does.

And please start talking about us as though we merit the same attention as any other group of dehumanized, Othered folk. Because we do.

References

Smith, Andrea. “The Problem with “Privilege.” Andrea 366. August 14, 2013. Accessed August 29, 2013. http://andrea366.wordpress.com/2013/08/14/the-problem-with-privilege-by-andrea-smith/.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

How Not to Have a Conversation about Racism

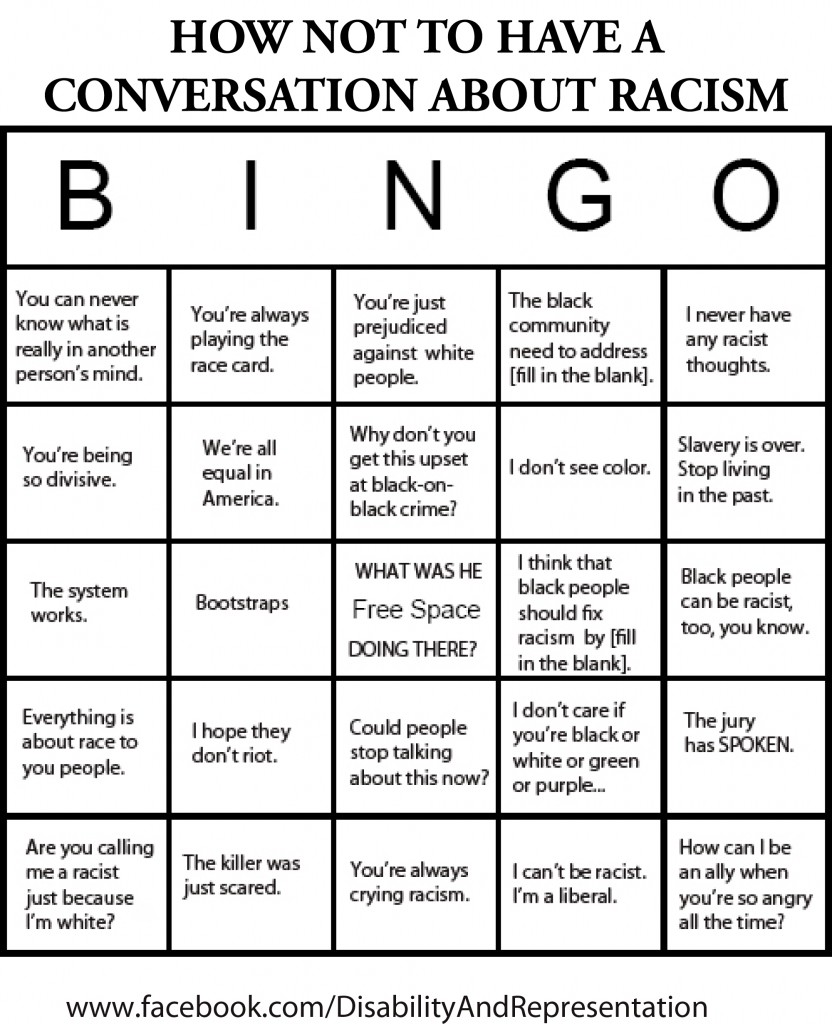

[The graphic is a Bingo card with 25 squares.

Title: How Not to Have a Conversation about Racism

Top row: You can never know what is really in another person's mind.

You're always playing the race card.

You're just prejudiced against white people.

The black community needs to address [fill in the blank].

I never have any racist thoughts.

Second row: You’re being so divisive.

We’re all equal in America.

Why don’t you get this upset at black-on-black crime?

I don’t see color.

Slavery is over. Stop living in the past.

Third row: The system works.

Bootstraps.

Free space: What was he doing there?

I think that black people should fix racism by [fill in the blank].

Black people can be racist too, you know.

Fourth row: Everything is about race to you people.

I hope they don’t riot.

Could people stop talking about this now?

I don’t care if you’re black or white or green or purple…

The jury has SPOKEN.

Last row: Are you calling me a racist just because I’m white?

The killer was just scared.

You’re always crying racism.

I can’t be racist. I’m a liberal.

How can I be an ally when you’re so angry all the time?

The text below the graphic reads www.facebook.com/DisabilityAndRepresentation.]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Staring But Not Seeing: A Review of Seeing a Color-Blind Future: The Paradox of Race by Patricia Williams

Following is my second critical annotation of the semester.

—

In her 1997 book, Seeing a Color-Blind Future: The Paradox of Race, Patricia Williams reflects upon the contradiction between our cultural insistence that color does not matter and the material reality of a world in which the construction of race has everything to do with one’s social, political, and economic experience. As I meditated on Williams’ words about the social construct and experience of race, I found myself noticing parallels to the social construct and experience of disability. While Williams does not include disability as a category of critical analysis, and while it would be appropriative to suggest that the experiences of race and disability are exactly the same, it is fair to say that similar issues come into play: the call to seeing the person, not the physical difference; the ways in which minority status is visible for critique, while the perspective of the majority becomes “natural” and fades into the background; the imperative to “pass”; the invitation to speak to one’s minority experience only for the benefit of those in the majority; the experience of being stared at but not seen clearly; and the necessity of battling against “scientific” representations that have little to do with lived experience. Unfortunately, while Williams protests the ways in which people can use one form of prejudice to argue against another, her analysis is marred by the fact that she uses pejorative disability metaphors in the service of her arguments against the insidious nature of racism.

An African-American professor of law at Columbia University and the author of the column “Diary of a Mad Law Professor” for The Nation, Williams is a prolific writer who has spent over 20 years tackling questions of social justice, race, ethnicity, class, and gender. She begins her book, however, with a personal story. She describes an incident at her son’s nursery school — an incident that derived from his white teachers’ well-intentioned imperative to be “color-blind,” but that ended up erasing the nature of her son’s racial experience. For most of his nursery school year, Williams tells us, his teachers believed that her son was color-blind. When asked what color the grass was, for example, he would respond that he either didn’t know or that it didn’t matter. After taking him to have his eyes examined and finding that he could see color perfectly well, Williams began to investigate why he was refusing to identify it (Williams 1997, 3). She learned that some of the children at his predominantly white school had been fighting about whether black people could be the “good guys” in playtime scenarios, and that the teachers had insisted that “it doesn’t matter…whether you’re black or white or red or green or blue” (Williams 1997, 3). She interpreted her son’s extreme refusal to identify color as an index of his anxiety that the teachers’ words would a) erase his own experience of color and b) deny his truth about the ways in which color matters in his relationships with others (Williams 1997, 4).

To put the imperative toward color-blindness another way: his teachers were telling the class to “see the person, not the color” in the same way that some in the disability community encourage able-bodied people to “see the person, not the disability” (Disability and Representation, 2012). In both cases, the imperative to see past the physical attribute, the insistence that the physical attribute does not matter, and the attempt to reach across difference by disregarding it derive from a desire to bring greater harmony to a world of injustice. The problem in both cases, of course, is that race and disability matter in that they are both social constructs that determine experience. Instead of taking a shortcut around the fact of race, Williams believes, we need to engage the experience of race in our culture in all of its manifestations (Williams 1997, 4-5). I would argue that exactly the same is true for disability. Until disability matters, not just as an indicator of personal experience, but also as a civil rights issue in which unjust social relations result in specific types of personal experience, there can be no significant progress toward the day when disability becomes a signifier of difference rather than a symbol of stigma and oppression.

One of the reasons, perhaps, that people rush to deny race and disability is that whiteness and normalcy are themselves invisible. Williams draws from whiteness theory when she writes that whiteness is an unmarked, de-racialized category; our culture does not tend to see whiteness as a race at all (Williams 2007, 6-7). Phil Smith extrapolates from whiteness theory to posit normal theory; for him, normalcy is analogous to whiteness in that it is simply an uncritiqued given and is considered “natural” (Smith 2004, 13). Perhaps, for those who are white and able-bodied, the desire to erase race and disability derives from a misplaced attempt to level the playing field. Perhaps people who insist that we “see the person, not the difference” are resting their view on the assumption that, because whiteness and normalcy are invisible, then race and disability should be invisible, too. Of course, the solution is not to make race and disability invisible, but to make whiteness and normalcy visible as categories of analysis. Until then, the invisibility of whiteness and normalcy will place people of color and disabled people in a realm apart. Williams writes that the invisibility of whiteness “permits whites to entertain the notion that race lives ‘over there’ on the other side of the tracks, in black bodies and inner-city neighborhoods, in a dark netherworld where whites are not involved” (Williams 1997, 7). As is the case with race, our cultural attitude toward disability is that it happens to someone else — someone who lives in a world apart, segregated from view (Murphy 1990, 110-111).

For both people of color and people with disabilities, this impetus toward invisibility takes the shape of pressure to “pass” so as not to intrude one’s difference upon the majority. Williams recounts the experience of her light-skinned cousin who could pass for white but identified herself in college as a member of the black law students’ association (Williams 1997, 53-54). When one of her professors found out that she had “outed” herself, Williams writes, he “grew agitated, annoyed, even confrontational”:

Why would she do such a thing, he wanted to know; why would she ‘label’ herself when she was so light-skinned and could so easily pass for white? My cousin was struck by how offended he was; he seemed to be implying that she had a obligation or a duty to pass and that her failure to do so was both impolitic and impolite. (Williams 1997, 54)

An analogous imperative to pass is the lot of disabled people who are able to hide their disabilities, as evidenced by Tobin Siebers’ remark that people with disabilities “must try to be as able-bodied as possible all the time” (Siebers 2011, 10). After reading Williams’ story about her cousin’s experience, I asked my circle of disabled friends whether anyone had had a similar experience about passing as nondisabled. A number of people had stories to tell. One autistic woman described her husband’s discomfort at her wearing bright yellow noise-blocking headphones and his worry that she was “disadvantaging” herself by choosing not to pass (Personal communication, 2012). Another autistic woman said that she had been accused of being impolite for not passing; after telling someone that her senses were overwhelmed and that she needed to find a quiet spot to recharge, the other person insisted that she continue passing, and chided her by saying “Lisa, you may have Aspergers, but you are intelligent enough to not act autistic” (Personal communication, 2012).

As a result of the cultural imperative to see race and disability as invisible, both are subject to what Williams calls “the forbidden gaze” (Williams 1997, 9). Children have a natural curiosity about difference (Brown 2010, 183) and, while our culture teaches them not to stare at non-normative people, it does not teach them how to engage difference (Williams 1997, 9). Because an interest in difference is both natural and culturally forbidden, people of color and disabled people find themselves in the paradoxical position of having to expose the nature of their experience for the use of others, right up until the point that their experience challenges the comfort of those doing the asking. People of color, Williams notes, “are ground down by the pendular stresses of having to explain what it feels like to be You … or, alternatively, placed in a kind of conversational quarantine of muteness” (Williams 1997, 9). Disabled people, too, find themselves in a similar quandary: they are either subject to questions from strangers about how they came to be disabled (Garland-Thomson 2000, 334) or they are ignored altogether (Murphy 1990, 118). In both cases, the center of gravity is the majority person. Minority people either perform for the majority person’s benefit, or they need to be quiet.

Interestingly enough, for both people of color and disabled people, the “forbidden gaze” turns into its opposite: intrusive staring. Williams refers to this propensity to stare as “racial voyeurism” (Williams 1997, 17). In one example among many, she describes the way in which tour buses in New York City bring tourists to black churches in order to “see the show” (Williams 1997, 22). Four hundred tourists arrive late, jockey for position for the best camera angles, photograph African Americans in prayer, and then disrupt the service by leaving en masse so as not to miss lunch (Williams 1997, 22-25). Williams considers the photographs a way of perpetuating the voyeuristic experience of watching “exotics”; she describes each picture as a “flat, dry, matted photographic relic to be spread out upon the coffee tables of faraway homes; the open-mouthed exotics, frozen in raucous song….” (Williams 1997, 25). Williams’ reflections on the voyeuristic nature of photography bring to mind Rosemarie Garland-Thomson’s statement that “photography authorizes staring” (Garland-Thomson 2002, 58) at disabled people, including those whom nondisabled people consider “wondrous” (Garland-Thomson 2002, 59-61) or “exotic” (Garland-Thomson 2002, 59). Through the eye of the camera, apparently, one can stare and circumvent the stricture against doing so.

And yet for all of this voyeurism, majority people often cannot clearly see the experience of race and disability at all. Williams recounts the discomfort of a colleague who was the only African-American attorney at a business luncheon where the waitstaff was entirely African-American. When the attorney mentioned to her white colleagues how uncomfortable she felt sitting among white professionals while being waited on by other people of color, her colleagues responded with profuse apologies for their choice of venue, all the while making it clear that they could not see the class barriers and social discomfort that were so painfully apparent to her (Williams 1997, 26-27). Siebers makes a similar observation about the experience of disabled people perceiving an architectural or social barrier that able-bodied people cannot see: “When we come to a barrier, we realize that our perception of the world does not conform to theirs, although they rarely have this realization. This difference in perception is a social barrier equal to or greater than any physical barrier…” (Siebers 2011, 51). In both cases, people in the minority are vividly aware of a core feature of their experience that is utterly invisible to those in the majority.

For both people of color and disabled people, the experience of not being seen properly sometimes takes the form of distorted representations in the guise of science — representations that rest on an ignorance of the daily lives and experiences of the people under study. Williams laments the way in which studies setting out to prove the genetic inferiority of black people periodically surface (Williams 1997, 51). Not only are the studies prejudicial, Williams notes, but they are also difficult to argue against; because they dress themselves up in the language of science and quantitative research, any rebuttal, in order to appear credible, must wear the same garb:

One of the great difficulties of pseudo-science is that it is so hard to refute just by saying it isn’t so… Black people find themselves responding endlessly to such studies before we can be heard on any other subject; we must credentialize ourselves as number-crunching social scientists quickly in order to be seen as even minimally intelligent… And it makes anyone who knows the great messy, unprovable contrary, who knows the indecipherable complexity of black or white people, who knows the reality and the potential of all humanity — us silly egalitarians — it makes us unintelligent, uninformed, powerless, and naïve. (Williams 1997, 49-50)

As Williams asserts, appeals to experience simply do not have a suitable degree of authority to counter anything that poses as science. Her analysis here reminds me of the charge of narcissism leveled at disabled people — the accusation that disability automatically renders one narcissistic — which is supposedly supported by the “science” of psychological research (Siebers 2011, 38-40). The parallel between racist pseudo-science and the pathologization of disability is telling, as is the difficulty of arguing against the “science” by bringing to bear experience that is not quantifiable. How does one use charts and graphs to prove empathy, or interest in others, or socially imposed suffering? How does one use quantitative measures to prove more than a small fraction of intelligence, talent, or insight?

Despite the fact that people of color and people with disabilities experience similar systems of oppressive representation, Williams does not pose disability as a critical category in Seeing a Color-Blind Future. She focuses on the intersections of race, ethnicity, gender, and class, and she notes the ways in which one form of prejudice is sometimes brought to bear in order to fight another; she calls this phenomenon “battling biases” (Williams 1997, 32). As an example of this conflict, she cites her experience of watching a counter person accuse a homeless customer of misogyny as a cover for her own class prejudice against him (Williams 1997, 31-32), and she concludes that this “revolving door of revulsions” is one of the ways in which prejudice remains entrenched (Williams 1997, 32).

Ironically enough, though, Williams engages in “battling biases” herself, using pejorative disability metaphors in order to analyze ways to break through other forms of prejudice. For example, she writes that “the eradication of prejudice, the reconciling of tensions across racial, ethnic, cultural, and religious lines, depends upon eradicating the little blindnesses, not just the big” (Williams 1997, 61), using blindness as a metaphor for a systemic failure to perceive the issues with which minority people struggle. In the same paragraph, she uses paralysis as a pejorative, speaking of the “paralyzing anxiety of well-meaning ‘white guilt’” as a metaphor for recalcitrance and lack of progress on race relations (Williams 1997, 61). In fact, she speaks of her son being pathologized as color-blind for his racial experience (Williams 1997, 5), but she doesn’t seem to realize that disabled people are equally pathologized for our disability experience, and that she is helping to perpetuate that pathologizing impulse.

An understanding of the commonalities between the experience of race and the experience of disability might have helped Williams bring disability into critical focus as a category of oppression and illuminate the ways in which both people of color and disabled people must struggle against similar obstacles. She might have helped make clear that disability, like race, is not simply a question of bodily difference, but an expression of a political and social experience. If Williams had brought disability into her analysis, she might have come to see that disability, like race, is an issue of civil rights and that, rather than deflecting our gaze from it, we must fully engage it.

References

Brown, Lerita M. Coleman. “Stigma: An Enigma Demystified.” In The Disability Studies Reader, edited by Lennard J. Davis, 179-192. New York, NY: Routledge, 2010.

Disability and Representation. “The Problem with Person-First Language: What’s Wrong with This Picture?” http://www.disabilityandrepresentation.com/2012/05/30/the-problem-with-person-first-language-whats-wrong-with-this-picture/. May 30, 2012. Accessed May 30, 2012.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. “Staring Back: Self-Representations of Disabled Performance Artists.” American Quarterly 52, no. 2 (Jun., 2000): 334-338. http://www.jstor.org/pss/30041845.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. “The Politics of Staring: Visual Rhetorics of Disability in Popular Photography.” In Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities, edited by Sharon L. Snyder, Brenda Jo Brueggemann, and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, 56-75. New York, NY: Modern Language Association of America, 2002.

Murphy, Robert Francis. The Body Silent. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1990.

Siebers, Tobin. Disability Theory. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011.

Smith, Phil. “Whiteness, Normal Theory, and Disability Studies.” Disability Studies Quarterly 24, no. 2 (2004): 1-24. http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/491/668.

Williams, Patricia. Seeing a Color-Blind Future: The Paradox of Race. New York, NY: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1997.

© 2012 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg