The New Derrick Coleman Duracell Ad Gets It Right

Every time that a new ad featuring a person with a disability comes out, I get ready to cringe. So when I learned that Duracell had released a video ad featuring Derrick Coleman, a fullback for the Seattle Seahawks and the first deaf offensive player in the NFL, I had to get myself in a good mood before I watched it. And certainly, if you look at how others are talking about the video, you’d be apprehensive, too. Hollywood Life ran the video under the headline Derrick Coleman: Watch The Deaf NFL Star’s Inspiring Commercial, and HuffPo crowed Deaf Seahawks Fullback Derrick Coleman Will Inspire You With This Commercial. The comments under the HuffPo article are painfully predictable, with people getting all inspired and teary.

So before I watched the video, I was bracing for inspiration porn. But that isn’t what I found. In fact, I thought that the commercial did an excellent job of showing that among the worst of the barriers that disabled people face are the ways in which we’re ignored, dismissed, and discounted. And, appropriately enough, it’s captioned. Take a look and see what you think:

From the beginning, the ad talks about the ways in which Coleman has been mistreated in his life. The ad doesn’t imply that being deaf is an impediment to being an athlete; in fact, it keeps the focus squarely on the people who discouraged Coleman on the basis of his deafness. “They told me it couldn’t be done. That I was a lost cause. I was picked on. And picked last.”

In fact, rather than saying, “I couldn’t hear” as the reason for his being ignored, the voiceover shifts the responsibility to the people who didn’t know how to communicate with him: “Coaches didn’t know how to talk to me.” To my mind, this is an absolutely stunning line. Whether anyone who put the ad together knows it or not, it comes straight out of the social model of disability. I was so amazed to see that line there that I played the ad several times, just to hear it.

And then, there is the double entendre of using “listen” to mean both “hear” and “take to heart”: “They gave up on me. Told me I should just quit. They didn’t call my name. Told me it was over. But I’ve been deaf since I was three, so I didn’t listen.”

There is great wordplay going on here. Not only does the double entendre work well, but being deaf metaphorically becomes an asset rather than a deficit. It’s his deafness that keeps him from listening to the voices of discouragement and believing in himself. In other words, in the logic of the video, he’s not in the NFL despite his deafness, but because of it. That twist on the mainstream narrative just floors me. And now that Coleman has been able to ignore the dismissals and the discouragement, he can hear the applause, the support, and the people on his side: “And now I’m here, with the loudest fans in the NFL cheering me on. And I can hear them all.” A deaf man saying that he can hear the crowd is a great way to confront the idea that being deaf is always about not hearing at all, and it makes Coleman a person with agency, not a passive victim of fate. He decides when he listens and when he doesn’t. No one else makes that decision for him.

The video ends with a tagline that could easily be read as inspiration porn: “Trust the power within.” Obviously, not all disabled people who believe in themselves experience inclusion, find employment, or get people to cheer for them. But I’m not reading the commercial as an “overcoming disability” story as much as a “don’t let the bastards grind you down” story. It’s not his disability that Coleman has overcome. It’s the microaggressions, the low expectations, and the prejudices of others that he’s pushed out of his head. To me, it’s not what he’s accomplished that is the main thing, but the fact that he stopped listening to the voices of dismissal and pursued something he loves to do.

Whether or not deflecting societal prejudice leads to any sort of tangible reward, simply deflecting it is crucial – and very difficult. No one should despair because of the attitudes of other people, and yet, so many of us do at one time or another. I like the idea of trusting the power within – not because it will help us to overcome all of the massive structural injustices we face, but because it engenders self-respect and self-love.

© 2014 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Inattention to Accessibility: Am I Part of the Disability Community, Too?

I am finding it more and more difficult to use words like “accessibility” and “inclusion” these days. Much of the problem with these words is that they assume an inside and an outside. If you’re “accessible,” to whom are you accessible? And if you’re “inclusive,” just who is outside that circle?

I ask these questions today out of a great deal of personal pain, feeling that very little inside the disability community is accessible to me or inclusive of me. I also ask these questions with a great deal of fear and trepidation, realizing that my already rather precarious position within the disability community could become even more precarious. But that apprehension has never stopped me before. I am, if nothing else, a perpetual outsider, because I will critique just about anything that I feel is out of kilter with stated principles or simply not working. I don’t engage in these critiques because I think my ethics are higher and better. I engage in them because if I don’t, I can’t ethically and emotionally navigate while maintaining my sense of who I am as a human being.

So here goes.

I am becoming more and more aware of how deep and wide is the chasm between my work in disability studies, on the one hand, and my work as a disabled person serving other disabled people, on the other. I split much of my time in disability land between working on a master’s thesis about disability culture and counter-narrative, and serving homeless and hungry disabled people who live in one of my city’s parks. As much as I love the academic work I’m doing — and as much as disability theory in general has enriched my life and my ability to understand all of the many forces that impinge upon it — there is very little connection between what I study and what I actually do in the world. Any time I’ve been in an academic program, this disconnect has troubled me, but it’s quite a bit more problematic when the field of study is about a pervasive political and social issue and not, for example, 19th-century English literature. What I am to make of the disconnect between my academic and social work? My current program, to its credit, emphasizes bringing theory into practice and yet, I find that there are not a lot of role models for how to do so.

In addition to this disconnect (or perhaps because of it?), I find that, even within disability studies and disability culture, I feel a sense of apartness. To begin to describe why, let me direct your attention toward where the last Society for Disability Studies conference was held: Orlando, Florida, just outside the entrance to Universal Studios.

For those unfamiliar with the needs of many neurologically atypical people, may I be blunt? Having a conference outside of the entrance to Universal Studios is rather like saying, “We’re having our conference across the street from the gates of hell. All are welcome!” Does anyone have any idea of the aversive impact of noise, crowds, visual overstimulation, and other sensory assaults that provoke an immediate OMG get me out of here response on the part of a great many of us? I’m not just talking about autistic people. I’m talking about people with a wide array of sensory, cognitive, chronic pain, and fatigue issues. Having a conference in such a place renders that conference inaccessible to many of us.

Apparently, this fact is not yet on the radar, because the conference organizers advertised the venue as the perfect place to talk about our “various realities”:

This year’s theme is “(Re)creating Our Lived Realities.” Playing off our particular location of Orlando– the home of Disney World, Universal Studios, and Epcot Center – this year’s conference theme seeks to explore the myriad ways in which we work to (de)construct the various realities in our lives.

Any place within 50 miles of Disney World, Universal Studios, and Epcot Center is going to be a no-go in terms of a conference for me, because using up all my spoons just to get in the door is not how I see accessibility working.

But then, of course, even if a conference or performance takes place in a more appropriate location, there is the inaccessibility of the conference or venue itself. For those of us with sensory and social differences, this inaccessibility is not limited to SDS by any means. It is pervasive. There is no thought given to the fact that walking into a venue with 20 or 50 or 100 or 500 people talking and socializing at once before the talk or the performance starts would put some of us into an overloaded, overstimulated, exhausted state. So what choice do we have? Walk into an inaccessible environment that causes pain and exhaustion? Or stay home?

Of course, there is just the appearance of choice here. There really is no choice for me. A performance venue or a conference might have ramps, ASL, CART, and any number of other accommodations, but I literally can’t walk into a sound-rich environment. It’s like a force field. It renders a venue just as inaccessible for me as if that venue did not have a ramp for wheelchair users. Walking into that kind of environment, and actually staying there, would be analogous to wheelchair users dragging themselves up the stairs in the absence of ramps and trying not to look too exhausted in the process. Possible, but hardly dignified, safe, or optimal.

Are my disabilities not as important?

A couple of weeks back, my friend Bill Peace wrote about an experience of being humiliated and excluded as a wheelchair user at the Humanities, Health, and Disabilities Study Workshop held at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. I shared his outrage over the treatment he received. A lot of people did. But I wonder where the outrage is for people such as myself, who could putatively walk into such a conference, but who could not last more than a few minutes because of the sensory overstimulation, the inability to filter sound, the difficulties socializing in conventional ways. Because let me tell you, if you can’t do those things, you’re not even going to get close to such a conference in the first place.

I have watched for years while some of my peers with visible disabilities are able to navigate the professional disability world in a way that I cannot. Not everyone with physical disabilities can navigate that world, obviously, and these folks are hardly representative, obviously, but they are there and they are quite visible, and they have access because they are neurotypical. I have the intelligence, the drive, the passion, the commitment, all of it, just as they do. But there is this very thin membrane that keeps me from entering into that world, and that thin membrane is all about the fact that I perceive experience differently and have a completely different way of being in the social and sensory world.

It’s a source of tremendous grief for me. It’s like being this close to reaching something and always having it out of reach. I’m an incredibly tenacious person, and my tenacity will not get me past that thin membrane, ever.

So the question of “Am I a part of this community too?” runs very deep in me, and I feel very conflicted about it. On the one hand, I feel that people respect what I do, and I am amazed at the sorts of conversations I’m able to have online in various venues. On the other hand, I’m keenly aware that I am on my own, as I always have been — and I’m cognizant of the limited nature of what’s available to me in the disability community. It’s almost like watching my place in the community phase in and out. Up to this point, I’ve been stuck in the feeling of “Well, that’s just how it is. I can’t tolerate noisy public settings or socialize in conventional ways.” But now I’m thinking, “Wait just a second. That’s locating disability in my body rather than in the environment. Is there some good reason that conferences and cultural events have to be a sensory and social nightmare? Is there some good reason that they end up on the list of inaccessible venues, much like most nondisabled venues? Is there good reason to exclude people for social and sensory differences?”

And the answer is always the same: “No, there is no good reason at all.”

I’m still waiting for the outrage over this lack of access. But I have the feeling I’m going to be waiting a very long time.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Ableist Language in Social Justice Spaces: It’s Not Just About the Words

One of the most difficult things for me about hanging out in Internet social justice spaces is the sheer amount of ableist language that gets thrown around there. Some of us point out the language and ask people to refrain from using it, but it rarely works. There are days that, if I wanted to, I could make a full-time job out of calling out every iteration of “He’s insane” and “What a moron” that people trot out to describe putatively “normal” folk who hold egregious views or dictate bad social policy. The pushback is usually along the lines of “We have more important things to do than talk about words” and “You’re asking too much” and “We shouldn’t have to protect you from nasty speech on the Internet.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about these kinds of discussions, because they all follow a similar pattern, and they all tend to focus on language. I find that focus enormously frustrating because, for me, it is never just about language. It’s about the level of devaluation and disability hatred that lies beneath the language. Much of this devaluation and hatred are unintentional, but that doesn’t make their impact on people’s lives any less.

The devaluation is acceptable and normal. People who are of non-normative intelligence or ability (narrowly defined) are simply considered less-than, so it’s the height of insult to call someone “stupid” or “a moron” or “a person with a low IQ.” Likewise, people with severe disability are considered less-than, so it’s perfectly acceptable to respond to an argument you don’t agree with by saying “If you believe that, you shouldn’t go out without a carer.” (Yes, I have heard someone say that in a social justice space. I could almost see the sneer.) When I hear these kinds of words, it’s the hatred and devaluation I’m responding to, because it’s everywhere, and it has a concrete impact on people’s lives, including my life, the lives of people I love, and the lives of people I serve.

Much of the time when we talk about ableism in social justice spaces, it’s not in the context of violence, lack of services, the valuation of ability, the construct of normalcy, hate crime, institutionalization, homelessness, inaccessibility, isolation, and a number of other issues that intersect in all kinds of ways with race, queer, class, and trans* issues. The fact that disability isn’t incorporated into these spaces as its own social justice issue leads to discussions on language that can end up feeling very theoretical and rather precious. The issue really isn’t about language at all, but about the pervasive impact of the kinds of hatred that the language betrays. If there is no discussion about the impact of that hatred, though, then questions of language lose their grounding.

For me, language discussions are always about concrete things. We think in language, and it forms how we address the problems that face us. It’s the problems that concern me — and the ways in which language reinforces them, frames them, and limits our ability to look at them.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Just a Drop in the Bucket

[The photograph shows ten open paper bags, standing upright, with five in the front and five in the back, against a white wall with grey shadow.]

Today, when I was passing out lunches in the park, one of the people there said to me, “It’s because of people like you that we’ll never starve.”

I was so taken aback. Sometimes, I only see how huge and systemic the problems are. I see lack of accessible housing, lack of accessible work places, lack of welcoming social structures, and lack of decent medical care as the root causes of so much homelessness amongst disabled people. And I see all of the systemic bigotries and inequalities and greed and broken social programs that are behind hunger and homelessness for so many people who are nondisabled.

And when I see all of that, I think that what I’m doing is just a drop in the bucket. I’m giving out 30 lunches a day, three days a week, when there are 1500 people living on the street in Santa Cruz alone, and many, many more going without food. If you think about what is happening across the country, and in how many ways this scenario is repeated in nearly every city, you see just how huge the problems are. In many ways, what I do really is just a drop in the bucket.

And then I remember that every person is a universe all their own, and that even saving one person from hunger or despair for one day is everything to that person. Everything. As the Talmud says:

“For this reason man was created alone, to teach you that whoever destroys a single soul, he is guilty as though he had destroyed a complete world; and whoever preserves a single soul, it is as though he had preserved a whole world.” (Sandhedrin 37a).

So I keep handing out food to people who see God in a brown paper bag and think I’m an angel, when the bag just contains a peanut butter sandwich, some cookies, and some fruit, and I am a very flawed and struggling person. But I try to channel the love that comes from The One Above, because I know that it is a balm to the soul. For people who have no refuge, the respect and kindness of others are reminders that they deserve justice in this world – including the ability to eat, to sleep, and to occupy space without fear.

Food feeds the belly. And kindness feeds the soul. And love provides a refuge, however fleeting.

And so I continue.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

The Stories We Tell: Coming to Terms with PTSD

One of the ways in which I navigate the cacaphony of competing discourses about disability, mental health, and just about everything else is to remind myself that we humans are always storytelling and that these discourses are just a series of stories. Along with eating, sleeping, and breathing, storytelling is what we do. Certainly, some things — like the sheer physicality of our bodies — aren’t just stories, and yet, we interpret even these things with stories about them.

I’ve been thinking a lot about stories lately — about the stories I tell about myself, about the stories I tell about other people, about the stories people have told about me, about the stories the media tells about everyone. I don’t fault people for telling stories. It’s what we do in order to makes sense out of our existence. As Arthur Frank writes, we are beings who, in order to make life habitable, must tell stories from the narrative resources available to us:

“To say that humans live in a storied world means not only that we incessantly tell stories. Stories are presences that surround us, call for our attention, offer themselves for our adaptation, and have a symbiotic existence with us. Stories need humans in order to be told, and humans need stories in order to represent experiences that remain inchoate until they can be given narrative form… We humans are able to express ourselves only because so many stories already exist for us to adapt, and these stories shape whatever sense we have of ourselves… ” (Frank 2012, 36)

One of the things that comforts me in this life, especially when I feel barricaded in by the absurdities of the things that people say, is to remember that we can rewrite these stories. If we are all inveterate storytellers — incorporating pieces of different narratives and creating new narratives from what exists — then we can always reinterpret and rewrite our stories. We are always free to engage that process. The problem is that stories often masquerade as fact, and we feel cut off from rewriting them at all.

To say that a story isn’t fact doesn’t mean that it’s entirely fiction. The stories that people tell always have truths in them somewhere. But they are not necessarily truths about the purported subjects of the story. A story about me might contain no truths about me at all. It might contain truths about the storyteller’s fears. It might contain truths about the storyteller’s trauma. It might contain truths about the storyteller’s desire for power.

There are two sets of stories that plague me. One set consists of the negative stories that people have told about me or about people like me. These stories tend to be pathologizing. Sometimes, they are so ubiquitous that it is difficult to have the strength to analyze, reinterpret, rewrite, and rethink them. But I’m coming to see that it’s the stories that I tell myself about myself that are the most troubling. Some of these stories incorporate the larger narratives, sometimes by design and sometimes unintentionally. Others are a rebellion against the larger narratives. It would be impossible to avoid responding to these narratives in some way.

These days, there is one story of mine whose validity I’ve been calling into serious question. It has to do with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

I’ve been dealing with PTSD for nearly my whole life. It began over 50 years ago, when I was four years old. I wasn’t diagnosed until I was in my thirties, and that diagnosis was like the heavens opening up and the angels singing. I know that it sounds like a strange thing to say about a PTSD diagnosis, but how else can I describe the way in which the PTSD markers — the core narrative elements of the PTSD story — mirrored my own story so well? Suddenly, someone was narrating my story in a way that I recognized.

Over time, I learned to navigate and handle PTSD triggers. I learned to distinguish between a trigger and actual danger. I learned how to detach and breathe and not react when the catastrophic thinking started. I got very good at it.

And it worked for a long time — until a whole new level of protracted trauma came along, triggered the old trauma, and gave me a whole new set of things to heal from. It took me a long time to recognize the new trauma as trauma, even though it went on for 11 years. My husband and I moved to California this year, just to get away from it.

In order to cope all these years, I’ve told myself a story about how well my old adaptive patterns were working. And so, in true PTSD fashion, I went back to the story that had served my survival as a child — the story in which I was always the person who has it together, who figures it out, who doesn’t show weakness, who helps other people, who never asks for help, who is always on top of things, and who is somehow beyond regular, garden-variety human needs. In other words, I have spent the past decade or more dealing with PTSD by telling myself a story that am not traumatized. Not really. Maybe I used to be. But surely, not anymore.

Right.

These days, that story is showing itself to be largely fiction. It began a few days ago, when my husband left for a visit to the east coast. I felt tremendous sadness. I looked at the sadness and thought, “What is that doing there?” I started to ask the sadness what it was trying to show me. And within three days, I got the message: my body is absolutely racked by trauma. For the first time in my life, I am fully inside my body and it is incredibly painful. The level of stress, of sheer physical tension, of never feeling at ease, of never feeling safe is constant. I look at some of the things I do, and I see how hypervigilant I am.

For instance, there is the way I sit on the sofa and use the computer. Here is a picture of my sofa:

[The photo shows a picture of a futon with a blue spread in a mandala design. There are four white pillows along the back and some beige carpeting is visible in front. A small wooden end table is visible to the right.]

[The photo shows a picture of a futon with a blue spread in a mandala design. There are four white pillows along the back and some beige carpeting is visible in front. A small wooden end table is visible to the right.]

It’s a futon that doubles as a guest bed. It looks very beautiful and comfortable, doesn’t it? But do I sit on this futon comfortably, leaning against the pillows, relaxing? No, I don’t. I sit on the edge, next to the table, with one foot on the ground, looking like I’m ready to fight an intruder who is about to mercilessly fuck with me.

You can see why my story about not being traumatized isn’t exactly working.

One of the things I have noticed recently about my attempt to fend off PTSD is that I have bifurcated the telling of my stories into public and private. In my public writing, I will talk about disability quite openly. But privately, I rarely talk about it at all. For instance, I wrote to my regular doctor today about whether she could help with a letter of medical necessity for a service dog for PTSD, and her response was along the lines of “We’ve never talked about your PTSD. We really should.”

It’s true. We never have. I wrote her back and basically said, “We’ve never talked about most of my disabilities. We really should.”

I’ve been seeing this doctor since May. She knows about my auditory processing disorder. She knows about the problem with my hip. But she does not know about my Asperger’s diagnosis. She does not know about my recent diagnosis of mixed receptive-expressive speech disorder. She does not know about my dypraxia. She does not know about my severe vestibular issues. She does not know about my sensory processing disorder. She only learned about my PTSD today, and I’ve been dealing with that since I was four.

Why hadn’t I talked to her? Partly, it’s that I’m so wounded by many of the assumptions that people make about my disabilities that I almost can’t bear it anymore. I have had so many bad experiences. And of course, the PTSD gets in the mix there, because the PTSD says, “Right. Don’t talk about it. Don’t show any vulnerability. Act like you’re fine.”

I told her why I hadn’t raised the issue. And her response was, “I understand your hesitation.”

So it looks like we’ll be having that conversation after all. I will also be seeing someone for EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapy. And I’m making tracks about getting a service dog. I can’t continue to talk about disability publicly and pretend privately like everything is fine.

I sometimes wonder whether passing as nondisabled isn’t sometimes an expression of PTSD. I mean, who wants to deal with all of the crap that gets thrown at us around disability if they can help it? Over the past couple of years, I’ve done everything I can to avoid as much of it as possible. But now I’m tired and my body hurts. It’s time to start telling the people I know in my daily life, not just in my writing.

Perhaps it’s safer to talk with all of you about it. If you’re reading this piece, it’s because you have some connection to the world of disability. But most people do not. And they’re the ones I have to start addressing, even when I feel like one more refusal, one more ignorant response, one more uncaring word is going to break my heart.

References

Frank, Arthur. W. “Practicing Dialogical Narrative Analysis.” In Varieties of Narrative Analysis, edited by James A. Holstein and Jaber F. Gubrium, 33-52. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2012.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

To the International Paralympic Committee: Let Victoria Arlen Compete

According to a recent article in The New York Times, disabled swimmer Victoria Arlen has been barred from competing in the Paralympics on the grounds that her disability is not permanent.

In her early teens, Victoria spent three years coming in and out of consciousness. Her legs are now paralyzed. She experiences muscle spasms in her upper body. She lives with severe stomach pain. She has seizures. Victoria was diagnosed with transverse myelitis and then given an additional diagnosis of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM).

Now a high-level athlete, Victoria won four medals and set a world record at the Paralympics last summer. This year, however, she will not be competing in the world championships. The International Paralympic Committee’s Peter Van de Vliet sums up the committee’s decision:

“The million-dollar question is, Is this a permanent impairment?” he said. “The rules stipulate that only people with permanent impairments can compete, and the one thing the doctor couldn’t explain was whether this was a permanent impairment.”

All of the many things wrong with this picture fall into three main categories:

1. The committee is narrowly defining disability as a medical condition, with no understanding that it is also a social position. The medical-model view of disability is very outdated, and it goes against the core reason for the existence of the Paralymics. If the point is to allow high-level athletes to compete because they are excluded from competing with able-bodied people, then the social model has to enter the picture. Can Victoria Arlen be competitive against able-bodied swimmers? Can she qualify for the Olympics according to able-bodied standards? No, she can’t. Who is the Paralympics for if not for a high-level disabled athlete like her?

2. The committee is adhering to a strict binary of disabled and non-disabled, when no such binary exists. Everyone has a body in a state of flux. At present, Victoria’s body is disabled. What is happening at present should be the only deciding factor — not what might happen in some mythic future. After all, who is to say that a cure for the condition of some other Paralympic athlete isn’t around the corner, and that Victoria Arlen’s condition will not become worse?

3. The committee is essentially asking Victoria Arlen whether she is “disabled enough,” when no such objective criteria exists. In many ways, the committee’s decision mirrors the controversy about whether Oscar Pistorius was too able-bodied to compete in the Olympics. To my mind, this is a very odd question to ask about any disabled person, but especially about someone with a very clear physical impairment. Oscar Pistorius is an amputee. Victoria Arlen’s legs are paralyzed. I fail to see how the possibility that Victoria’s body might one day be ambulatory generates sufficient ambiguity to override the fact that she currently cannot purposefully move her legs.

The only deciding factor should be whether Victoria Arlen is disabled now, which she clearly is. It’s absurd for disabled people to draw these kinds of lines and act to exclude one another based on outmoded and questionable criteria. When it comes to disability, it’s time for the Paralympics to get into the 21st century

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

A Trick of the Mind: Advocating for My Body

I’ve heard many people say that they find it much easier to advocate for someone else than for themselves. I’ve certainly found that to be the case. If I see something going wrong for someone else, I can step up directly on that person’s behalf without hesitation. On my own behalf, though, I tend to try to wind my way around the problem — denying it, looking for alternative solutions, trying to convince myself it’s not a big deal — until I finally can’t take it anymore and speak up.

I had an experience this week that put me in mind of a way to get past the resistance to advocating on my own behalf. I now think about advocacy as advocating for my body, rather than for myself. When I think of my body as asking me to advocate on its behalf, I find it much easier to say, “Okay, sure. I can speak right up.”

I stumbled upon this trick of the mind this past Sunday, when an online meeting that had been scheduled for 2 pm got canceled at the last minute because some of the people couldn’t make it. My body went into a neurological tailspin. The problem really wasn’t that I was inconvenienced, per se; the problem was that I had structured my entire day around the meeting in order to take care of my body. I had to save spoons in the morning just to get ready for the meeting, so I had done nothing else that morning at all. I hadn’t scheduled anything after the meeting so that I’d have time to rest. With disability in the picture, I have to make sure that any time I know that I’ll be working hard (and a meeting with other people is always working hard), I clear a lot of space around it. When I’ve done that and a meeting gets canceled, I have a hard time shifting course. It’s not because I am inflexible and impatient, but because everything in the day has been structured around the thing that didn’t happen, and my body has garnered all of its energies to prepare for the working time and the resting time on either end. It doesn’t quite know what to do when it’s been for naught.

When I found out that the meeting had been canceled, I got upset, and I realized that I needed to say something to the other people about it. I know that things come up at the last minute that can’t be helped, and I can go with that, but I needed people to know that, when it’s possible, I need more notice. I need people to remember that my body works differently from theirs, and that what looks like a two-hour meeting is a whole day affair for me.

What really surprised me about the situation was that I was not angry at the people involved at all. They are all great people and it wasn’t their fault. They didn’t know how my body works. If they had known about this particular need, I’m sure they would have factored that into the process. Instead of anger, all I saw was that my body was yelling at me to defend it. I had always mistaken that level of urgency for anger, but it isn’t. It’s my body screaming at me: “Come on, Rachel. Come on. Say something. NOW. DEFEND MY NEEDS. Help! HELP! Don’t hesitate. Act!”

It was so amazing to look at my body as though it were speaking to me. It made it so much easier to advocate on its behalf. The level of compassion I felt for myself was so much greater than what I usually feel in a situation that involves the collision of my body with the able-bodied world. I usually have a war with myself about whether it’s even worth it to speak up; I usually worry whether I will be met with resistance, anger, impatience, or ignorance. But when I was able to look at my body’s signals, I just thought, “Oh, my body is in serious distress. I need to say something about how to keep my body out of pain. Right now.”

I got an apology, which I appreciated, because I knew I’d been heard. But really, an apology wasn’t necessary, because no one had known in advance what the impact would be. The most important thing was that I was able to say, “My body works differently from yours and it is yelling at me to say something, and I am going to stand up for it.” That’s huge for me. And it’s a welcome change.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Doing Social Justice: Thoughts on Ableist Language and Why It Matters

The economy has been crippled by dept.

You’d have to be insane to want to invade Syria.

They’re just blind to the suffering of other people.

Only a moron would believe that.

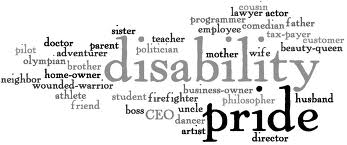

Disability metaphors abound in our culture, and they exist almost entirely as pejoratives. You see something wrong? Compare it to a disabled body or mind: Paralyzed. Lame. Crippled. Schizophrenic. Diseased. Sick. Want to launch an insult? The words are seemingly endless: Deaf. Dumb. Blind. Idiot. Moron. Imbecile. Crazy. Insane. Retard. Lunatic. Psycho. Spaz.

I see these terms everywhere: in comment threads on major news stories, on social justice sites, in everyday speech. These words seem so “natural” to people that they go uncritiqued a great deal of the time. I tend to remark on this kind of speech wherever I see it. In some very rare places, my critique is welcome. In most places, it is not.

When a critique of language that makes reference to disability is not welcome, it is nearly inevitable that, as a disabled person, I am not welcome either. I might be welcome as an activist, but not as a disabled activist. I might be welcome as an ally, but not as a disabled ally. I might be welcome as a parent, but not as a disabled parent. That’s a lot like being welcomed as an activist, and as an ally, and as a parent, but not as a woman or as a Jew.

Many people have questions about why ableist speech matters, so I’ll be addressing those questions here. Please feel free to raise others.

1. Why are you harping so much on words, anyway? Don’t we have more important things to worry about?

I am always very curious about those who believe that words are “only” words — as though they do not have tremendous power. Those of us who use words understand the world through them. We use words to construct frameworks with which we understand experience. Every time we speak or write, we are telling a story; every time we listen or read, we are hearing one. No one lives without entering into these stories about their fellow human beings. As Arthur Frank writes:

“Stories work with people, for people, and always stories work on people, affecting what people are able to see as real as possible, and as worth doing or best avoided. What is it about stories – what are their particularities – that enables them to work as they do? More than mere curiosity is at stake in this question, because human life depends on the stories we tell: the sense of self that those stories impart, the relationships constructed around shared stories, and the sense of purpose that stories both propose and foreclose.” (Frank 2010, 3)

The stories that disability metaphors tell are deeply problematic, deeply destructive, and deeply resonant of the kinds of violence and oppression that disabled people have faced over the course of many centuries. They perpetuate negative and disempowering views of disabled people, and these views wind their ways into all of the things that most people feel are more important. If a culture’s language is full of pejorative metaphors about a group of people, that culture is not going to see those people as fully entitled to the same housing, employment, medical care, education, access, and inclusion as people in a more favored group.

2. What if a word no longer has the same meaning it once did? What’s wrong with using it in that case?

Ah yes. The etymology argument. When people argue word meanings, it generally happens in a particular (and largely unstated) context. With regard to ableist metaphors, people argue that certain meanings are “obsolete,” but such assertions fail to note the ways in which these “obsolete” words resonate for people in marginalized groups.

For example, I see this argument a great deal around the word moron, which used to be a clinical term for people with an intellectual disability. I have a great-aunt who had this label and was warehoused in state hospitals for her brief 25 years of life. So when I see this word, it resonates through history. I remember all of the people with this designation who lived and died in state schools and state mental hospitals under conditions of extreme abuse, extreme degradation, extreme poverty, extreme neglect, and extreme suffering from disease and malnutrition. My great-aunt lay dying of tuberculosis for 10 months under those conditions in a state mental hospital. The term moron was used to oppress human beings like her, many of whom are still in the living memory of those of us who have come after.

Moron — and related terms, like imbecile and idiot – may no longer be used clinically, but their clinical use is not the issue. They were terms of oppression, and every time someone uses one without respect for the history of disabled people, they disrespect the memory of the people who had to carry those terms to their graves.

3. What’s wrong with using bodies as metaphors, anyway?

Think about it this way: Consider that you’re a woman walking down the street, and someone makes an unwanted commentary on your body. Suppose that the person looks at you in your favorite dress, with your hair all done up, and tells you that you are “as fat as a pig.” Is your body public property to be commented upon at will? Are others allowed to make use of it — in their language, in your hearing, without your permission? Or is that a form of objectification and disrespect?

In the same way that a stranger should not appropriate your body for his commentary, you should not appropriate my disabled body — which is, after all, mine and not yours — for your political writing or social commentary. A disabled body should not appear in articles about how lame that sexist movie is or how insane racism is. A disabled body should be no more available for commentary than a nondisabled one.

The core problem with using a body as a metaphor is that people actually live in bodies. We are not just paralyzed legs, or deaf ears, or blind eyes. When we become reduced to our disabilities, others very quickly forget that there are people involved here. We are no longer seen as whole, living, breathing human beings. Our bodies have simply been put into the service of your cause without our permission.

4. Aren’t some bodies better than others? What’s wrong with language that expresses that?

I always find it extraordinary that people who have been oppressed on the basis their physical differences — how their bodies look and work — can still hold to the idea that some bodies are better than others. Perhaps there is something in the human mind that absolutely must project wrongness onto some kind of Other so that everyone else can feel whole and free. In the culture I live in, disabled bodies often fit the bill.

A great deal of this projection betrays a tremendous ignorance about disability. I have seen people defend using mental disabilities as a metaphor by positing that all mentally disabled people are divorced from reality when, in fact, very few mental disabilities involve delusions. I have seen people use schizophrenic to describe a state of being divided into separate people, when schizophrenia has nothing to do with multiplicity at all. I have seen people refer to blindness as a total inability to see, when many blind people have some sight. I have seen people refer to deafness as being locked into an isolation chamber when, in fact, deaf people speak with their hands and listen with their eyes (if they are sighted) or with their hands (if they are not).

Underlying this ignorance, of course, is an outsider’s view of disability as a Bad Thing. Our culture is rife with this idea, and most people take it absolutely for granted. Even people who refuse to essentialize anything else about human life will essentialize disability in this way. Such people play right into the social narrative that disability is pitiful, scary, and tragic. But those of us who inhabit disabled bodies have learned something essential: disability is what bodies do. They all change. They are all vulnerable. They all become disabled at some point. That is neither a Good Thing nor a Bad Thing. It is just an essential fact of human life.

I neither love nor hate my disabilities. They are what they are. They are neither tragic nor wonderful, metaphor nor object lesson.

5. Disabled people aren’t really oppressed. Are they?

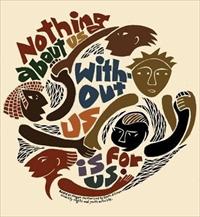

Yes, disabled people are members of an oppressed group, and disability rights are a civil rights issue. Disabled people are assaulted at higher rates, live in poverty at higher rates, and are unemployed at higher rates than nondisabled people. We face widespread exclusion, discrimination, and human rights violations. For an example of what some of the issues are, please see the handy Bingo card I’ve created, and then take some time over at the Disability Social History Project.

6. If my disabled friend says it’s okay to use these words, doesn’t that make it all right to use them?

Please don’t make any one of us the authority on language. It should go without saying, but think for yourself about the impact of the language you’re using. If you stop using a word because someone told you to, you’re doing it wrong. It’s much better if you understand why.

7. I don’t know why we all have to be so careful about giving offense. Shouldn’t people just grow thicker skins?

For me, it is not a question of personal offense, but of political and social impact. If you routinely use disability slurs, you are adding to a narrative that says that disabled people are wrong, broken, dangerous, pitiful, and tragic. That does not serve us.

8. Aren’t you just a member of the PC police trying to take away my First Amendment rights?

No. The First Amendment protects you from government interference in free speech. It does not protect you from criticism about the words you use.

9. Aren’t you playing Oppression Olympics here?

No. I’ve never said that one form of oppression is worse than another, and I never will. In fact, I am asking that people who are marginalized on the basis of the appearance or functioning of their bodies — on the basis of gender identity, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, size, and disability — get together and talk about the ways in which these oppressions weave through one another and support one another.

If you do not want disability used against your group, start thinking about what you’re doing to reinforce ableism in your own speech. If you do not want people of color to be called feeble-minded, or women to be called weak, or LGBT people to be called freaks, or fat people to be called diseased, or working-class people to be called stupid — all of which are disability slurs — then the solution isn’t to try to distance yourself from us and say, No! We are not disabled like you! The solution is to make common cause with us and say, There is nothing wrong with being disabled, and we are proud to stand with you.

10. Why can’t we use disability slurs when the target is actually a nondisabled person?

To my knowledge, the president of the United States is not mentally disabled, and yet his policies have been called crazy and insane. Most Hollywood films are made by people without mobility issues, and yet people call their films lame. Someone who has no consciousness of racism or homophobia will be called blind or deaf to the issues, and yet, such lack of consciousness runs rampant among nondisabled people.

So why associate something with a disability when it’s what nondisabled people do every single day of the week? As far as I can see, lousy foreign policy, lousy Hollywood films, and lousy comments about race and sexual orientation are by far the province of so-called Normal People.

So come on, Normal People. Start owning up to what’s yours. And please remember that we disabled folks are people, not metaphors in the service of your cause.

References

Disability Social History Project. http://www.disabilityhistory.org. Accessed September 14, 2013.

Facebook. “Disability and Representation.” https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=638151876196123&set=a.535870946424217.126038.447484845262828&type=1. Accessed September 14, 2013.

Frank, Arthur W. Letting Stories Breathe: A Socio-Narratology. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2010.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Why So Many Fail to Understand Systemic Oppression

I was recently in a discussion about the ways in which people of color are disproportionately targeted by the police (think: stop-and-frisk, among other rights violations), disproportionately incarcerated, and disproportionately imprisoned for long stretches. As is often the case in these kinds of discussions, someone came blundering in with a “solution” — the “solution” being that people of color just need to be compliant with police officers and not do anything at all that could possibly be construed as suspicious or alarming. In other words, people of color simply had to act “normal” and all would be well.

I kept reading those words over and over, because I found them so shocking. It wasn’t just that the ideas were wrong — that they evinced an ignorance of racism and an idealized sense of control. It’s that they were based on an outlook that I once believed was grounded in fact: that society is “just” and that all I had to do to be safe was to do everything “right.”

That was a lifetime ago. At some point, I realized that there was no way to do it “right” because, in the eyes of the society in which I live, I am already seen as “wrong.” This assumption of wrongness is why marginalized people get the attention of the police, not to mention other authority figures, for driving while black, for walking while trans, for standing while disabled. We’re already considered “wrong” in the first place.

Some people’s bodies are themselves considered provoking. Not our intentions. Not our attitudes. Not our actions. OUR BODIES. To understand this very basic fact goes against the whole notion that the society one lives in is just — that the good are rewarded and that the guilty are punished. It’s deeply terrifying to realize how truly irrational people are when it comes to the arbitrary meanings they place on human bodies. It means that entire systems are based on completely arbitrary and irrational standards. It goes against the whole Western notion that humans are rational and enlightened beings.

It’s a very hard thing to wrap your mind around until it comes your way. And even when it does come your way, it’s still something that is difficult to face. This is one of the reasons that even people inside marginalized groups can fail to grasp the systemic injustices directed against their bodies. Or if they do grasp it, they can fail to understand the irrationality of the hatred directed toward other people’s bodies. So you find gay and lesbian people who are racist and transphobic, and you find people of color who are homophobic and ableist, and you find transgender people who are ageist and fatphobic, and you find disabled people who are misogynist and classist. Depending on who you talk to, you’ll find a multitude of permutations of all of these bigotries, including the horrifying specter of internalized hatred against one’s own body.

To realize that these valuations are simply arbitrary — that there is no good reason at all to suspect a body just for being a body — means to recognize that we are all at risk. Stigma is a moveable feast. It is mercilessly easy to move from a privileged category to a stigmatized category. Just ask anyone who has ever been diagnosed with a disability after living with the privileges of able-bodiedness, or anyone who has ever become fat after being thin, or anyone who has become old after a lifetime of looking youthful. The whole notion that the society is constructed along rational lines comes crashing down. And then you have to reconstruct your sense of how it works, piece by piece.

You’ll find other people who have woken up and found a new way of seeing. But you’ll never really believe again that the world you live in is just.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Smoochie Paraplegic Cat: When Disability Tropes Take on a Life of Their Own

On Love Meow: A Blog for Ultimate Cat Lovers, there is an article with the following title:

Smoochie Paraplegic Cat Doesn’t Let Her Disability Define Her

I kid you not. That’s a real headline. And it’s not on a parody site. (I checked.) Love Meow is just a site with lots of cute pictures and videos of cats.

I love cats. I love pictures and videos of cats. I have even been known to share them on Facebook with appropriate expressions of squeeee! and OMG THIS IS SO CUTE. And Smoochie is freakin’ adorable. Oh dear God. That face! I love her wheels. I love that her owners cared enough to get her some wheels. And I love that she has a happy life.

Now that we’ve established that I’m not some cat-hating curmudgeon bent on ruining everyone’s fun little cat-fest, let’s get to the disability rhetoric, because it’s just out of control. Along with the title, the first paragraph is almost enough for a bingo card:

Smoochie the cat doesn’t let her disability stop her. Being paraplegic, she doesn’t want anyone to pity her. With love and a pair of wheels, Smoochie now lives a happy life that inspires many.

So let’s see: so far, we have the person-first (cat-first?) trope (“doesn’t let her disability define her”), the overcoming trope (“doesn’t let her disability stop her”), the pity trope (couched as a plea to not pity little Smoochie), and the inspiration trope (“lives a happy life that inspires many”).

Already, I’m confused. First of all, I didn’t realize that cats struggle with identity issues. I mean, do cats argue about whether disability “defines” them? I think not. I’m also not sure that cats know that disability is supposed to stop them, being as they’re not all caught up in the discourse that passes for reality amongst human beings. I’m also not sure that cats know what pity is.

Yes, yes, I know that people project things onto animals all the time. But this is really over the top. It’s like someone took all the disability tropes in the world and plastered them on cute little Smoochie. These tropes are repeated throughout the article:

Cats with disabilities are no different from cats without disabilities: “The pure joy she shows when they put her in the wheelchair is as if she never had the disability. She runs around and plays just like any other kitties.”

See the cat, not the disability: “Smoochie never lets her disability define her.”

Cats with disabilities, and their heroic rescuers, should have their own Inspiring After-School Special: “Her humans believed in her and gave her a second chance at life, and now she’s happy and healthy as the mascot at West Side Cats, inspiring many with her story.”

Supercrip cats know how to get it done: “Smoochie is paraplegic but she doesn’t let it stop her.”

Disabled cats are inspirational: “Smoochie is now the mascot at West Side Cats, inspiring many with her story.”

It’s fascinating the ways in which these tropes amble around the culture, attaching themselves to any creature that is disabled. If anyone doubts that disability is a social construct, I give you Exhibit A: The Case of Smoochie the Cat.

Read it and weep.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg