On Insults in Dialogue

Here I am, late to the party, but this article on Skepchick got me thinking. Apparently, last month, there was a big blow-up about ableist language used in another post, and this Skepchick article addresses the issue. I don’t agree with much of the article, and I don’t hang out in the Skeptic community, but all that is really beside the point. What I find so interesting is the amount of words spent — both in the article and in the comments section — on the whole problem of whether it’s okay to use an ableist insult, whether anyone should care whether people are triggered, and whether we should all just get over being offended.

To me, words like “idiot” and “moron” and “stupid” are ableist, so I think that people were absolutely right to raise the issue. However, I think that there is something quite — I don’t know, odd? — about arguing over what kind of insults are allowed in dialogue. The whole problem could be solved by sticking to content, respecting the dignity of other people, and staying away from insults altogether, yes? Then you’d never end up with an ableist insult coming out of your mouth or off the keys of your computer.

The purpose of an insult is to hurt, to shame, and to demean. So is it any surprise that people who are uninvolved in the argument end up as collateral damage? Is it any wonder that sexism, racism, homophobia, transphobia, and ableism start creeping in when the insults start flying? After all, if an insult is meant to hurt, to shame, and to demean, then what better way to do it than to make implicit comparisons to people who are already hurt, shamed, and demeaned?

This is why I do my best to stay away from insults and why I’m not interested in anyone coming on my blog and launching them. It’s not just painful to the people involved; it has the potential to add to the marginalization of already marginalized people. And no, I don’t think we ought to be compiling lists of non-bigoted insults. I think we ought to be able to talk to one another with dignity about how to fix the problems in the world we live in.

But obviously, I’m a dreamer. Being harsh and cruel is so acceptable now that I often wonder why I even write these kinds of words. And then I remember that I write them so that others who feel as I do will know that they’re not alone. I write for people like myself, who would rather have an insult be a rare event and not a common and acceptable mode of communication.

I hope our culture can move back to valuing respectful dialogue. Of course, there is no reason to romanticize the past. It’s true that there have always been all kinds of disrespect and indignities visited upon millions of people, and respectful dialogue was not the experience of the many. I’ve experienced disrespect, indignity, and assault in my own life, and I come from a people that experienced it for many centuries. What I remember, though, from my earlier years as an activist, is that people who wanted to create a just world valued respecting people. They valued raising up people who were not respected into the light of dignity. They felt that the only way to create peace and justice was to model it. What I see now is exactly the opposite — that we’ve given into the idea that, because the world is a brutal and violent place, it’s somehow all right to be nasty with each other.

I don’t see our society valuing respectful dialogue any time soon — perhaps not even in my lifetime. I’m realizing that what I’ve worked so hard to do all of my adult life — to engage in civil dialogue while staying rooted in all of my emotions — is no longer of value to most people in the society I live in. This realization saddens me more than words can say.

© 2014 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Petty Cruelties

Today I was talking to a friend who lives on disability and has been homeless for several months. He told me a story that simultaneously made me angry and broke my heart.

The other day, while he was standing on the street, he saw something that delighted him, and he wanted to get a picture of it. He was getting ready to use his smartphone to take the photo when a couple of women started talking in very loud voices about how he should not have a smartphone.

“That man is begging and he has a $400 smartphone? How dare he! That’s just wrong. He shouldn’t have anything like that!” And on and on.

In point of fact, he got the phone for $70. But really, who cares what it cost? It doesn’t matter, because in the eyes of some people, poor folks should be completely destitute before they deserve anything. And even if they were completely destitute, you know that these very same self-righteous good citizens would still do nothing to help. If my friend were on the street with nothing but the clothes on his back, they’d spit at him and call him a lazy bum because being poor is, in their eyes, some sort of moral and social crime.

I am a very shy person when it comes to initiating social interactions. But if I’d been standing there while these women started in on this subject, you could not have shut me up. I’d have told them where to shove it and invited them to take their privileged asses down the road.

This is the mentality that keeps people on the street. You want homeless folks to get housing and jobs? How are they supposed to do that without a phone, without decent clothing, without food, without shelter, without all of the things that they need?

People and their petty cruelties just break my heart sometimes. My friend is a kind and decent person in a terrible situation who just wanted to take a photo of something that made him happy. And random people passing on the road — people who have never spoken to him, people who have never given him anything, people who have all the food and shelter they could ever need — couldn’t even let him have a happy moment. They had to open their mouths. They had to say something. They had to fuck it up. They couldn’t have a moment of consideration for someone else and just keep their damned mouths shut.

There is so much suffering out there, and the systemic problems are so huge. When people try to find some measure of happiness in the midst of it all, why try to take that from them?

I despair of humanity at times. These cruel, petty microaggressions just tear me up. And then I look at my friend, who has more decency and kindness than almost anyone I’ve ever met. People like him keep me going when I think that the world is beyond redemption.

I hope I help to keep him going, too.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Shunning, Shaming, Renaming

For the past 11 years, I have been shunned.

Not socially rejected. Shunned. By what used to be my synagogue community. For falling in love with my partner. For my partner falling in love with me.

He was serving as the rabbi when we met. After we made our relationship known, people who had formerly welcomed me would not speak to me. I lost my closest friends in the community. Others reacted with hostility to me in public. They put their bodies between my partner and me, blocking our path to each other. They held meetings to vent about our relationship. They responded to my friendliness with walls of coldness and detachment.

My partner lost his job. We lost the spiritual home that we loved. We lost our sense of safety. We had to move away — not once, but twice, because the first move wasn’t far enough.

After 10 years of marriage, we’ve moved 3000 miles away to start again. I am 54 and he is 68.

Starting over one more time wasn’t in the plan. And yet here we are. Together.

——–

Shunning is a form of psychological violence. It brings out all the hidden shame you didn’t think you carried anymore.

Sexual shame. Body shame. There-is-something-wrong-with-me shame. I-don’t-really-deserve-anything shame. The shame you thought you’d dispelled when you faced your childhood. The shame you thought you’d healed when you found religion. The shame that lurks in a culture in which we are never all right just as we are – not really. The shame that is always beneath the surface when the body is always suspect.

It’s a shame that thrives on silence – that proliferates in silence, until you feel shame for even daring to push up against being shamed. Until you feel ashamed of your anger at your silencing. Until you feel ashamed of your resistance against what has been taken. Until you feel ashamed to speak the truth of your own experience. Until opening one door in your soul to let in the light causes three more doors to close because you don’t deserve to live in the light.

Until you feel as though you can’t even breathe.

——-

Shunning creates an absence that is difficult to describe because its hallmark is silence – a frightening, wearying silence. Because others refuse to speak, to acknowledge your presence, to treat you as though you matter, there is no way to respond. A response assumes a listener. How do you respond when no one is listening? Words do not matter. All that matters is the shaming – the unnamed, unnameable shaming.

Nearly seven years into the shunning, I was diagnosed with the disabilities I’d had all my life: Asperger’s syndrome, sensory processing disorder, auditory processing disorder, vestibular issues, dyspraxia. That’s when the language of shame began to break its awful silence and bind my soul with words. Now the shame had names: Deficit. Disorder. Brokenness.

My body was wrong. My body was broken. I would never be right. No matter how many ways I starved my body, how kosher I kept my kitchen, how clean I kept my house, how intensely my empathy flowed, how kind I was to strangers, and how much I loved my family – it didn’t matter. I’d never, ever be right.

The feelings of wrongness that the shunning engendered and the feelings of wrongness that the language of deficit engendered became intertwined. In the light of my disabilities, I began to look at the shunning, and I began to wonder: Had I become a target because my differences, though unnamed, were so obvious? Did people believe that I was somehow less-than? And in my worst moments, I secretly wondered Were they right?

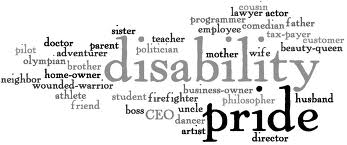

Not only had I been shunned by my community, but I was also entering a whole new identity as an openly disabled person, with all of the social isolation and rejection that came along with it. With my disabilities becoming more apparent in mid-life, I began to realize what most disabled people already know: that the world marginalizes us because of the ways in which our bodies work. I had been able to pass as nondisabled for much of my life, but by the time I was 50, full-time passing was no longer an option. I no longer had the energy. I had to work with my body rather than against it. I had to assert my needs. I couldn’t pretend to be normal anymore. And that put me outside the world as I had known it.

In the face of this dual marginalization, I lived my life in a battle between anger and despair. When the anger rose, I was determined to turn the language of deficit and disorder and brokenness into the language of blessing. If the “experts” said that people like me were hyperfocused on our obsessions, I said that I was passionate about the things I loved. If they said that we had splinter skills, I said that I had talents. If they said that we had deficits, I spoke of brilliant adaptations.

I reclaimed, and renamed, and rejustified my existence.

And suddenly, I realized that it was all wrong. Because ultimately, this reclamation project wrote me out of its script altogether. I was no longer talking about myself. I was talking about the gifts of Asperger’s.

My analytical mind, my focus, my visual acuity, my way with words, my musical talent, my passion for justice, my honesty, my sensitivity, my gentleness: these had always been my gifts. Not the gifts of Asperger’s. My gifts. But they were no longer mine. All those precious moments of pride and work and love and family that had made up the fabric of my life had been stolen from me and made the fabric of a construct I had never named.

The gifts of Asperger’s. The gifts of an abstraction, of a word that a stranger had created.

And as my sense of myself diminished, the shame became such a constant presence that I couldn’t remember what it meant to live without it. I couldn’t taste my food without the shame sticking in my throat. I couldn’t go to sleep at night without it laying down beside me. I couldn’t speak without using words embedded in it. I spoke in the oppressor’s tongue. I thought in the oppressor’s words. I was always ready to flinch, to apologize, to justify.

——-

I sometimes think about the process of healing in terms of uprooting the shame, but I’m not sure whether uprooting is the right word. I’ve been uprooted enough, and I know that tearing out something by the roots tears up the rich fertile earth around it, too. I’m not sure what the right words are. I just know that the unshaming process cannot be done piecemeal. For me, there is no working through the shame, or coming to terms with the shame, or getting past the shame, to use the language to which I was once so attached.

There is only a radical claim to my own body, to my own mind, to my own soul. There is only a radical claim to love my own being – a being to which no one else has the right to lay claim but me.

Perhaps others have the privilege of being able to rely on the names that others give. Perhaps others can readily find mirrors in which they see images that they recognize. But so many of us cannot. So many of us cannot rely upon a world of deficit and shame and apology to give us our names. The words of that world are not our words. They do not speak us.

So I find others who are learning how to speak their own names. I join with others who are unapologetic about how their bodies look, how their minds work, how they experience the world. I journey with others who are rejecting the language of shame and who are learning to open all the doors of the soul to let in the light.

I hope to meet you one day on this road.

—

I wrote this post in April of 2013 and it appeared on The Body is Not an Apology’s tumblr blog on May 1, 2013. It is reprinted here with permission.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Passing and Disability: Why Coming Out as Disabled Can Be So Difficult

Yesterday was National Coming Out Day. I officially came out as bisexual, and it was a celebration. No angst. No fear. No second thoughts. Just a celebration.

It was a such a contrast with coming out as disabled at the end of 2008, with all of the fear and dread that attended that decision. There have been many times since then that I’ve thought that coming out as disabled was the worst decision I’d ever made in my life. If I could have put the toothpaste back in the tube at those moments, I would have.

Of course, I’m a few years down the road now and feel much more comfortable, proud, and confident. But oh, what a process! And of course, the process never ends. I always have internalized shame, and hatred, and fear to root out of my head. And I still have to deal with a world of people who don’t understand the physical and social experience of disability. But in general, I navigate these waters much better than I did at the outset.

It’s very difficult to come out as disabled, I think, because we face the dual reality that most people a) hate our bodies absolutely unapologetically and b) consider that hatred entirely natural. It’s for this reason that they can use disability slurs constantly and think nothing of it. It’s for this reason that they can segregate and exclude us as though we’re substandard merchandise to return to the manufacturer. It is still considered natural to react with revulsion against us in a way that other groups have fought against more successfully — not entirely successfully, obviously, but more successfully.

Partly, we face this hatred because our culture worships control and denies the fragile and ever-changing life of the body. Partly, we face this hatred because the medical model has taken over as a metaphor for human life. People are no longer evil. People no longer make bad choices. People are no longer victimized by oppression. People no longer act out of ignorance, or selfishness, or greed. No. Now they’re sick, crazy, brain-dead, retarded, mentally ill, have low IQs, and on and on.

In the face of this hatred, it’s very, very difficult to convince people that you love your disabled body because it’s the one you live in. You say that you love your body, and people look at you as though you don’t quite understand your own reality.

My body hurts a lot these days. But I still love it. It’s the body I was born with. It enables me to experience life. Without it, I’d have no life at all. I might not love every sensation in my body, but I love my body, even on the hardest days, because it gives me life.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

This Week in the Park: How Our Fellow Human Beings are Living

As I go out and distribute food to people living in the park, I see and hear things that nearly break me apart. Here’s what I’ve seen and heard over the past week. This is how our fellow human beings are living.

An elderly amputee stops me to talk about shooting squirrels for food.

A vet in his 60s tells me that a blind man is losing weight and coughing up blood. The man moans all night. He is dying. Outside. Alone.

Two men sitting on a bench tell me that they have had nothing but water for two days.

Two women are lying on a blanket together, comforting each other. One has a black eye.

A squad car arrives in the meadow where homeless people congregate and sleep during the day. A police officer and two park rangers are telling a group of people to move on. The group consists of men and women of all ages, including an elderly woman. They might have been drinking or smoking, which are forbidden in the park. The park rangers are often checking to see what is going on in the meadow.

People in the group are screaming at the police officer and the rangers. Some are gathering their possessions and dragging them away. On the pedestrian bridge above, people with food and clothing and shelter are staring at and mocking the homeless folks being dispersed below.

I maintain very clear boundaries when I am in the park. If I see the police or the park rangers talking to people, I hang back. They have a job to do and I give them space to do it. Before I go over to people and offer food, I observe them very carefully. If I sense anything awry, I move on. If people scream at me, I don’t get into it. If other people scream at them, I just observe and continue on.

My job is to offer food, kindness, respect, and courtesy to people who are hungry and homeless. I see so much now that I never saw before. Most people don’t see it. I didn’t see it. Now I can’t unsee it. I don’t want to unsee it, ever.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

The Stories We Tell: Coming to Terms with PTSD

One of the ways in which I navigate the cacaphony of competing discourses about disability, mental health, and just about everything else is to remind myself that we humans are always storytelling and that these discourses are just a series of stories. Along with eating, sleeping, and breathing, storytelling is what we do. Certainly, some things — like the sheer physicality of our bodies — aren’t just stories, and yet, we interpret even these things with stories about them.

I’ve been thinking a lot about stories lately — about the stories I tell about myself, about the stories I tell about other people, about the stories people have told about me, about the stories the media tells about everyone. I don’t fault people for telling stories. It’s what we do in order to makes sense out of our existence. As Arthur Frank writes, we are beings who, in order to make life habitable, must tell stories from the narrative resources available to us:

“To say that humans live in a storied world means not only that we incessantly tell stories. Stories are presences that surround us, call for our attention, offer themselves for our adaptation, and have a symbiotic existence with us. Stories need humans in order to be told, and humans need stories in order to represent experiences that remain inchoate until they can be given narrative form… We humans are able to express ourselves only because so many stories already exist for us to adapt, and these stories shape whatever sense we have of ourselves… ” (Frank 2012, 36)

One of the things that comforts me in this life, especially when I feel barricaded in by the absurdities of the things that people say, is to remember that we can rewrite these stories. If we are all inveterate storytellers — incorporating pieces of different narratives and creating new narratives from what exists — then we can always reinterpret and rewrite our stories. We are always free to engage that process. The problem is that stories often masquerade as fact, and we feel cut off from rewriting them at all.

To say that a story isn’t fact doesn’t mean that it’s entirely fiction. The stories that people tell always have truths in them somewhere. But they are not necessarily truths about the purported subjects of the story. A story about me might contain no truths about me at all. It might contain truths about the storyteller’s fears. It might contain truths about the storyteller’s trauma. It might contain truths about the storyteller’s desire for power.

There are two sets of stories that plague me. One set consists of the negative stories that people have told about me or about people like me. These stories tend to be pathologizing. Sometimes, they are so ubiquitous that it is difficult to have the strength to analyze, reinterpret, rewrite, and rethink them. But I’m coming to see that it’s the stories that I tell myself about myself that are the most troubling. Some of these stories incorporate the larger narratives, sometimes by design and sometimes unintentionally. Others are a rebellion against the larger narratives. It would be impossible to avoid responding to these narratives in some way.

These days, there is one story of mine whose validity I’ve been calling into serious question. It has to do with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

I’ve been dealing with PTSD for nearly my whole life. It began over 50 years ago, when I was four years old. I wasn’t diagnosed until I was in my thirties, and that diagnosis was like the heavens opening up and the angels singing. I know that it sounds like a strange thing to say about a PTSD diagnosis, but how else can I describe the way in which the PTSD markers — the core narrative elements of the PTSD story — mirrored my own story so well? Suddenly, someone was narrating my story in a way that I recognized.

Over time, I learned to navigate and handle PTSD triggers. I learned to distinguish between a trigger and actual danger. I learned how to detach and breathe and not react when the catastrophic thinking started. I got very good at it.

And it worked for a long time — until a whole new level of protracted trauma came along, triggered the old trauma, and gave me a whole new set of things to heal from. It took me a long time to recognize the new trauma as trauma, even though it went on for 11 years. My husband and I moved to California this year, just to get away from it.

In order to cope all these years, I’ve told myself a story about how well my old adaptive patterns were working. And so, in true PTSD fashion, I went back to the story that had served my survival as a child — the story in which I was always the person who has it together, who figures it out, who doesn’t show weakness, who helps other people, who never asks for help, who is always on top of things, and who is somehow beyond regular, garden-variety human needs. In other words, I have spent the past decade or more dealing with PTSD by telling myself a story that am not traumatized. Not really. Maybe I used to be. But surely, not anymore.

Right.

These days, that story is showing itself to be largely fiction. It began a few days ago, when my husband left for a visit to the east coast. I felt tremendous sadness. I looked at the sadness and thought, “What is that doing there?” I started to ask the sadness what it was trying to show me. And within three days, I got the message: my body is absolutely racked by trauma. For the first time in my life, I am fully inside my body and it is incredibly painful. The level of stress, of sheer physical tension, of never feeling at ease, of never feeling safe is constant. I look at some of the things I do, and I see how hypervigilant I am.

For instance, there is the way I sit on the sofa and use the computer. Here is a picture of my sofa:

[The photo shows a picture of a futon with a blue spread in a mandala design. There are four white pillows along the back and some beige carpeting is visible in front. A small wooden end table is visible to the right.]

[The photo shows a picture of a futon with a blue spread in a mandala design. There are four white pillows along the back and some beige carpeting is visible in front. A small wooden end table is visible to the right.]

It’s a futon that doubles as a guest bed. It looks very beautiful and comfortable, doesn’t it? But do I sit on this futon comfortably, leaning against the pillows, relaxing? No, I don’t. I sit on the edge, next to the table, with one foot on the ground, looking like I’m ready to fight an intruder who is about to mercilessly fuck with me.

You can see why my story about not being traumatized isn’t exactly working.

One of the things I have noticed recently about my attempt to fend off PTSD is that I have bifurcated the telling of my stories into public and private. In my public writing, I will talk about disability quite openly. But privately, I rarely talk about it at all. For instance, I wrote to my regular doctor today about whether she could help with a letter of medical necessity for a service dog for PTSD, and her response was along the lines of “We’ve never talked about your PTSD. We really should.”

It’s true. We never have. I wrote her back and basically said, “We’ve never talked about most of my disabilities. We really should.”

I’ve been seeing this doctor since May. She knows about my auditory processing disorder. She knows about the problem with my hip. But she does not know about my Asperger’s diagnosis. She does not know about my recent diagnosis of mixed receptive-expressive speech disorder. She does not know about my dypraxia. She does not know about my severe vestibular issues. She does not know about my sensory processing disorder. She only learned about my PTSD today, and I’ve been dealing with that since I was four.

Why hadn’t I talked to her? Partly, it’s that I’m so wounded by many of the assumptions that people make about my disabilities that I almost can’t bear it anymore. I have had so many bad experiences. And of course, the PTSD gets in the mix there, because the PTSD says, “Right. Don’t talk about it. Don’t show any vulnerability. Act like you’re fine.”

I told her why I hadn’t raised the issue. And her response was, “I understand your hesitation.”

So it looks like we’ll be having that conversation after all. I will also be seeing someone for EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapy. And I’m making tracks about getting a service dog. I can’t continue to talk about disability publicly and pretend privately like everything is fine.

I sometimes wonder whether passing as nondisabled isn’t sometimes an expression of PTSD. I mean, who wants to deal with all of the crap that gets thrown at us around disability if they can help it? Over the past couple of years, I’ve done everything I can to avoid as much of it as possible. But now I’m tired and my body hurts. It’s time to start telling the people I know in my daily life, not just in my writing.

Perhaps it’s safer to talk with all of you about it. If you’re reading this piece, it’s because you have some connection to the world of disability. But most people do not. And they’re the ones I have to start addressing, even when I feel like one more refusal, one more ignorant response, one more uncaring word is going to break my heart.

References

Frank, Arthur. W. “Practicing Dialogical Narrative Analysis.” In Varieties of Narrative Analysis, edited by James A. Holstein and Jaber F. Gubrium, 33-52. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2012.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

In Defense of Politeness: Talking to People in the Park

It’s become something of a truism — in both social justice circles and the larger society — to say that politeness is outmoded. In fact, many people view politeness as a tool of oppression, as though it has no utility except to shame people angry at their oppression into compliance: You need to be more polite, the privileged say. Otherwise, I won’t listen to you.

I have experienced this tactic. To me, this is an absolute misuse of the very notion of politeness. It should never be used as a way to shut people up. To the contrary: politeness, when used properly, enables people to feel safe enough to speak.

Of course, politeness has its limits. If someone physically attacks me, I’m not going to be polite while fighting for my life. If someone attempts to derail an argument by telling me that I need to be more polite — and has no interest in hearing me out no matter how well-spoken I am — I can be blunt about calling that out. There are many times and places in which being polite is out of the question. And because of those times and places, politeness has gotten a bad name.

I was raised in an era in which social forms were far more important than they are now. Our parents and teachers drilled into us the need to say please, thank you, and you’re welcome; to say excuse me if you had to pass in front of someone; to hold the door for the next person. But for us, it wasn’t an empty social form or an expression of deference. To the contrary: it was a sign of respect.

Although I can be very, very blunt, I can also be polite to a fault. I am amazed at the ways in which all those long-ago lessons live in me — the ways in which I instinctively go to them as I walk through my life. Politeness still lives in my bones, no matter how blunt I may otherwise be.

I have been calling upon politeness early and often these days as I distribute bag lunches to people living in the park, many of whom are disabled. Because they experience so little politeness at the hands of other people, I find it very, very important to exercise politeness when talking with people who have no homes. These people, whether disabled or not, are ignored, spat on, told to get a job, and chased out of public spaces. So when I talk to people, I am unfailingly courteous.

When I approach people who are sleeping, I take care to not wake them up. A lot of people can’t sleep during the night — because sleeping outdoors is illegal at night in Santa Cruz — so they sleep during the day. If I see people sleeping, I’ll walk up to them very softly and leave a bag of food at their feet, or behind them, or on top of their carts. But occasionally, my presence startles people and they wake up. One person became quite hostile. My response is always polite: I’m sorry that I disturbed your rest. I’ll just leave your lunch here for you.

If a person is awake, I will say May I offer you some food? If I have to step over a person’s camp in order to reach that person, I will ask whether it is all right for me to step on a blanket or a tarp.

If someone says thank you to me, I always say, you’re very welcome.

To my mind, this is no empty social form. To the contrary, it is a form of social justice. I am making right a wrong. I am overturning the cultural imperative to look down on disabled people, to look down on people living in poverty, to see them as unworthy of basic human decency. I am letting people know that they deserve my courtesy and my respect.

And people are almost always polite to me in return. It is rare that a person doesn’t treat me with courtesy. Very, very rare. People introduce themselves and ask my name. They ask after how I’m doing. They offer to help distribute food to their friends. They say God bless. I see less and less of this kind of courtesy among people with a great deal more. I find it reassuring wherever I meet it.

Kindness flows through these social forms. Far from being an exercise in compliance and silencing, they are an experience of connection and being seen.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Doing Social Justice: Thoughts on Ableist Language and Why It Matters

The economy has been crippled by dept.

You’d have to be insane to want to invade Syria.

They’re just blind to the suffering of other people.

Only a moron would believe that.

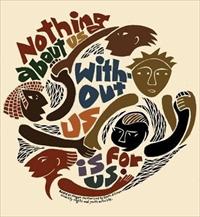

Disability metaphors abound in our culture, and they exist almost entirely as pejoratives. You see something wrong? Compare it to a disabled body or mind: Paralyzed. Lame. Crippled. Schizophrenic. Diseased. Sick. Want to launch an insult? The words are seemingly endless: Deaf. Dumb. Blind. Idiot. Moron. Imbecile. Crazy. Insane. Retard. Lunatic. Psycho. Spaz.

I see these terms everywhere: in comment threads on major news stories, on social justice sites, in everyday speech. These words seem so “natural” to people that they go uncritiqued a great deal of the time. I tend to remark on this kind of speech wherever I see it. In some very rare places, my critique is welcome. In most places, it is not.

When a critique of language that makes reference to disability is not welcome, it is nearly inevitable that, as a disabled person, I am not welcome either. I might be welcome as an activist, but not as a disabled activist. I might be welcome as an ally, but not as a disabled ally. I might be welcome as a parent, but not as a disabled parent. That’s a lot like being welcomed as an activist, and as an ally, and as a parent, but not as a woman or as a Jew.

Many people have questions about why ableist speech matters, so I’ll be addressing those questions here. Please feel free to raise others.

1. Why are you harping so much on words, anyway? Don’t we have more important things to worry about?

I am always very curious about those who believe that words are “only” words — as though they do not have tremendous power. Those of us who use words understand the world through them. We use words to construct frameworks with which we understand experience. Every time we speak or write, we are telling a story; every time we listen or read, we are hearing one. No one lives without entering into these stories about their fellow human beings. As Arthur Frank writes:

“Stories work with people, for people, and always stories work on people, affecting what people are able to see as real as possible, and as worth doing or best avoided. What is it about stories – what are their particularities – that enables them to work as they do? More than mere curiosity is at stake in this question, because human life depends on the stories we tell: the sense of self that those stories impart, the relationships constructed around shared stories, and the sense of purpose that stories both propose and foreclose.” (Frank 2010, 3)

The stories that disability metaphors tell are deeply problematic, deeply destructive, and deeply resonant of the kinds of violence and oppression that disabled people have faced over the course of many centuries. They perpetuate negative and disempowering views of disabled people, and these views wind their ways into all of the things that most people feel are more important. If a culture’s language is full of pejorative metaphors about a group of people, that culture is not going to see those people as fully entitled to the same housing, employment, medical care, education, access, and inclusion as people in a more favored group.

2. What if a word no longer has the same meaning it once did? What’s wrong with using it in that case?

Ah yes. The etymology argument. When people argue word meanings, it generally happens in a particular (and largely unstated) context. With regard to ableist metaphors, people argue that certain meanings are “obsolete,” but such assertions fail to note the ways in which these “obsolete” words resonate for people in marginalized groups.

For example, I see this argument a great deal around the word moron, which used to be a clinical term for people with an intellectual disability. I have a great-aunt who had this label and was warehoused in state hospitals for her brief 25 years of life. So when I see this word, it resonates through history. I remember all of the people with this designation who lived and died in state schools and state mental hospitals under conditions of extreme abuse, extreme degradation, extreme poverty, extreme neglect, and extreme suffering from disease and malnutrition. My great-aunt lay dying of tuberculosis for 10 months under those conditions in a state mental hospital. The term moron was used to oppress human beings like her, many of whom are still in the living memory of those of us who have come after.

Moron — and related terms, like imbecile and idiot – may no longer be used clinically, but their clinical use is not the issue. They were terms of oppression, and every time someone uses one without respect for the history of disabled people, they disrespect the memory of the people who had to carry those terms to their graves.

3. What’s wrong with using bodies as metaphors, anyway?

Think about it this way: Consider that you’re a woman walking down the street, and someone makes an unwanted commentary on your body. Suppose that the person looks at you in your favorite dress, with your hair all done up, and tells you that you are “as fat as a pig.” Is your body public property to be commented upon at will? Are others allowed to make use of it — in their language, in your hearing, without your permission? Or is that a form of objectification and disrespect?

In the same way that a stranger should not appropriate your body for his commentary, you should not appropriate my disabled body — which is, after all, mine and not yours — for your political writing or social commentary. A disabled body should not appear in articles about how lame that sexist movie is or how insane racism is. A disabled body should be no more available for commentary than a nondisabled one.

The core problem with using a body as a metaphor is that people actually live in bodies. We are not just paralyzed legs, or deaf ears, or blind eyes. When we become reduced to our disabilities, others very quickly forget that there are people involved here. We are no longer seen as whole, living, breathing human beings. Our bodies have simply been put into the service of your cause without our permission.

4. Aren’t some bodies better than others? What’s wrong with language that expresses that?

I always find it extraordinary that people who have been oppressed on the basis their physical differences — how their bodies look and work — can still hold to the idea that some bodies are better than others. Perhaps there is something in the human mind that absolutely must project wrongness onto some kind of Other so that everyone else can feel whole and free. In the culture I live in, disabled bodies often fit the bill.

A great deal of this projection betrays a tremendous ignorance about disability. I have seen people defend using mental disabilities as a metaphor by positing that all mentally disabled people are divorced from reality when, in fact, very few mental disabilities involve delusions. I have seen people use schizophrenic to describe a state of being divided into separate people, when schizophrenia has nothing to do with multiplicity at all. I have seen people refer to blindness as a total inability to see, when many blind people have some sight. I have seen people refer to deafness as being locked into an isolation chamber when, in fact, deaf people speak with their hands and listen with their eyes (if they are sighted) or with their hands (if they are not).

Underlying this ignorance, of course, is an outsider’s view of disability as a Bad Thing. Our culture is rife with this idea, and most people take it absolutely for granted. Even people who refuse to essentialize anything else about human life will essentialize disability in this way. Such people play right into the social narrative that disability is pitiful, scary, and tragic. But those of us who inhabit disabled bodies have learned something essential: disability is what bodies do. They all change. They are all vulnerable. They all become disabled at some point. That is neither a Good Thing nor a Bad Thing. It is just an essential fact of human life.

I neither love nor hate my disabilities. They are what they are. They are neither tragic nor wonderful, metaphor nor object lesson.

5. Disabled people aren’t really oppressed. Are they?

Yes, disabled people are members of an oppressed group, and disability rights are a civil rights issue. Disabled people are assaulted at higher rates, live in poverty at higher rates, and are unemployed at higher rates than nondisabled people. We face widespread exclusion, discrimination, and human rights violations. For an example of what some of the issues are, please see the handy Bingo card I’ve created, and then take some time over at the Disability Social History Project.

6. If my disabled friend says it’s okay to use these words, doesn’t that make it all right to use them?

Please don’t make any one of us the authority on language. It should go without saying, but think for yourself about the impact of the language you’re using. If you stop using a word because someone told you to, you’re doing it wrong. It’s much better if you understand why.

7. I don’t know why we all have to be so careful about giving offense. Shouldn’t people just grow thicker skins?

For me, it is not a question of personal offense, but of political and social impact. If you routinely use disability slurs, you are adding to a narrative that says that disabled people are wrong, broken, dangerous, pitiful, and tragic. That does not serve us.

8. Aren’t you just a member of the PC police trying to take away my First Amendment rights?

No. The First Amendment protects you from government interference in free speech. It does not protect you from criticism about the words you use.

9. Aren’t you playing Oppression Olympics here?

No. I’ve never said that one form of oppression is worse than another, and I never will. In fact, I am asking that people who are marginalized on the basis of the appearance or functioning of their bodies — on the basis of gender identity, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, size, and disability — get together and talk about the ways in which these oppressions weave through one another and support one another.

If you do not want disability used against your group, start thinking about what you’re doing to reinforce ableism in your own speech. If you do not want people of color to be called feeble-minded, or women to be called weak, or LGBT people to be called freaks, or fat people to be called diseased, or working-class people to be called stupid — all of which are disability slurs — then the solution isn’t to try to distance yourself from us and say, No! We are not disabled like you! The solution is to make common cause with us and say, There is nothing wrong with being disabled, and we are proud to stand with you.

10. Why can’t we use disability slurs when the target is actually a nondisabled person?

To my knowledge, the president of the United States is not mentally disabled, and yet his policies have been called crazy and insane. Most Hollywood films are made by people without mobility issues, and yet people call their films lame. Someone who has no consciousness of racism or homophobia will be called blind or deaf to the issues, and yet, such lack of consciousness runs rampant among nondisabled people.

So why associate something with a disability when it’s what nondisabled people do every single day of the week? As far as I can see, lousy foreign policy, lousy Hollywood films, and lousy comments about race and sexual orientation are by far the province of so-called Normal People.

So come on, Normal People. Start owning up to what’s yours. And please remember that we disabled folks are people, not metaphors in the service of your cause.

References

Disability Social History Project. http://www.disabilityhistory.org. Accessed September 14, 2013.

Facebook. “Disability and Representation.” https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=638151876196123&set=a.535870946424217.126038.447484845262828&type=1. Accessed September 14, 2013.

Frank, Arthur W. Letting Stories Breathe: A Socio-Narratology. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2010.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Holding Fast To My Own Experience

I’ve been wanting to write this post for a long time, but it’s taken me awhile to get enough distance on the whole issue to be able to write about it out of power rather than out of fear.

As many of you know, I’ve done a lot of work critiquing research into autism and empathy — both in my academic life and online at my Autism and Empathy site. One of the driving factors behind this work was an experience I’ve been afraid to talk about. To put it as briefly as possible: the research conclusions surrounding an alleged lack of empathy in autistic people made me question when I am really empathetic at all, and they filled me with doubt and dread for a very long time.

I’ve spent much of my adult life describing myself as an empath, and I have always read emotional and social process very well. But then my autism diagnosis came along and voila! I was supposed to be deficient in empathy. In fact, I read study, after study, after study showing that autistic people have an empathy disorder, and the cold voices of authority started getting into my head. That was bad. Very bad. What Sartre wrote about the Jewish people applied equally well to me as an individual:

“They have allowed themselves to be poisoned by the stereotype that others have of them, and they live in fear that their acts will correspond to this stereotype.” (Sartre 1960, 95)

“Poisoned” is right. I was sick with fear and doubt. A year or two ago, I finally got up the courage to check the whole empathy question out with the people who know me best: my husband and my kid. I started with the kid, who was still a teenager at the time. I said, “Ash, do you think I’m empathetic?”

Ash looked at me in a way that only teenagers can look at mothers: with a mixture of impatience, love, and something bordering on anger for wasting their time. With an eye roll, my kid spoke the following immortal words;

“Mom. YES. You are very empathetic. Exhibit A: MY ENTIRE LIFE.”

I felt relieved. Later in the evening, after my husband came home, I related my conversation with Ash and poured out my relief as he made himself toast at the kitchen counter. His response? He was uncharacteristically brief. “Good,” he said. “No need to ask this question again.”

Somehow, those two conversations allayed my doubts. I couldn’t write about it for a long time, though. I couldn’t acknowledge publicly the kinds of doubt the research had raised in me. But I can do so now, because I’ve come to understand that I wasn’t just having an experience of personal insecurity. I’ve come to realize that this kind of doubt is common for people in all kinds of marginalized groups. I’ve finally seen the ways in which those with cultural authority speak for us, ask us to prove our experience with numbers and graphs and research papers, and then tell us that our experience means nothing because it doesn’t match their findings.

The rather obvious conclusion to draw from research findings that don’t match reality is that the research findings are wrong, but of course, that rarely happens. The research findings take on the authority of truth, and the experiences of people who actually live in the bodies being researched mean very little.

Put another way: The truth means very little. The story that is constructed, however, means everything, and we find ourselves spending massive amounts of energy arguing against the story, both within ourselves and with everyone else. Patricia Williams writes about studies on race in a way that rings true for me as I recall all the many hours I’ve spent refuting autism research:

“One of the great difficulties of pseudo-science is that it is so hard to refute just by saying it isn’t so. The logical structure — if not the substance — of pseudo-science posits what purports to be fact; it requires counter-fact to make counter-arguments. Black people find themselves responding endlessly to such studies before we can be heard on any other subject; we must credentialize ourselves as number-crunching social scientists quickly in order to be seen as even minimally intelligent… Real numbers, real science — it’s what school teaches us to revere. And it makes anyone who knows the great messy, unprovable contrary, who knows the indecipherable complexity of black or white people, who knows the reality and the potential of all humanity — us silly egalitarians — it makes us unintelligent, uninformed, powerless, and naïve.” (Williams 1998, 49-50)

“Real numbers, real science” — how do these things even begin to compete with the delicious, messy, complex, living, breathing nature of human experience? They don’t. They can’t. They can never even come close. They only put us into hierarchies: black/white, normal/abnormal, able/disabled, and so many others.

Do I regret that I spent so many hours critiquing the research? Do I wish I’d said instead, “To hell with your studies, to hell with your questionnaires, to hell with the careers you’ve built on the backs of people like me”? In some ways, yes. But in other ways, I am glad to have been able to spend some time in the belly of the monster, because I got to know its way of being very, very well and I got to see how very barren the belly is.

The monster doesn’t scare me anymore. It’s been banished. And when people try to raise the monster back up, I find myself wondering why they’re wasting their time believing in an apparition.

References

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Anti-Semite and Jew. New York, NY: Grove Press, 1960.

Williams, Patricia. Seeing a Color-Blind Future: The Paradox of Race. New York, NY: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1998.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Why So Many Fail to Understand Systemic Oppression

I was recently in a discussion about the ways in which people of color are disproportionately targeted by the police (think: stop-and-frisk, among other rights violations), disproportionately incarcerated, and disproportionately imprisoned for long stretches. As is often the case in these kinds of discussions, someone came blundering in with a “solution” — the “solution” being that people of color just need to be compliant with police officers and not do anything at all that could possibly be construed as suspicious or alarming. In other words, people of color simply had to act “normal” and all would be well.

I kept reading those words over and over, because I found them so shocking. It wasn’t just that the ideas were wrong — that they evinced an ignorance of racism and an idealized sense of control. It’s that they were based on an outlook that I once believed was grounded in fact: that society is “just” and that all I had to do to be safe was to do everything “right.”

That was a lifetime ago. At some point, I realized that there was no way to do it “right” because, in the eyes of the society in which I live, I am already seen as “wrong.” This assumption of wrongness is why marginalized people get the attention of the police, not to mention other authority figures, for driving while black, for walking while trans, for standing while disabled. We’re already considered “wrong” in the first place.

Some people’s bodies are themselves considered provoking. Not our intentions. Not our attitudes. Not our actions. OUR BODIES. To understand this very basic fact goes against the whole notion that the society one lives in is just — that the good are rewarded and that the guilty are punished. It’s deeply terrifying to realize how truly irrational people are when it comes to the arbitrary meanings they place on human bodies. It means that entire systems are based on completely arbitrary and irrational standards. It goes against the whole Western notion that humans are rational and enlightened beings.

It’s a very hard thing to wrap your mind around until it comes your way. And even when it does come your way, it’s still something that is difficult to face. This is one of the reasons that even people inside marginalized groups can fail to grasp the systemic injustices directed against their bodies. Or if they do grasp it, they can fail to understand the irrationality of the hatred directed toward other people’s bodies. So you find gay and lesbian people who are racist and transphobic, and you find people of color who are homophobic and ableist, and you find transgender people who are ageist and fatphobic, and you find disabled people who are misogynist and classist. Depending on who you talk to, you’ll find a multitude of permutations of all of these bigotries, including the horrifying specter of internalized hatred against one’s own body.

To realize that these valuations are simply arbitrary — that there is no good reason at all to suspect a body just for being a body — means to recognize that we are all at risk. Stigma is a moveable feast. It is mercilessly easy to move from a privileged category to a stigmatized category. Just ask anyone who has ever been diagnosed with a disability after living with the privileges of able-bodiedness, or anyone who has ever become fat after being thin, or anyone who has become old after a lifetime of looking youthful. The whole notion that the society is constructed along rational lines comes crashing down. And then you have to reconstruct your sense of how it works, piece by piece.

You’ll find other people who have woken up and found a new way of seeing. But you’ll never really believe again that the world you live in is just.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg