The New Derrick Coleman Duracell Ad Gets It Right

Every time that a new ad featuring a person with a disability comes out, I get ready to cringe. So when I learned that Duracell had released a video ad featuring Derrick Coleman, a fullback for the Seattle Seahawks and the first deaf offensive player in the NFL, I had to get myself in a good mood before I watched it. And certainly, if you look at how others are talking about the video, you’d be apprehensive, too. Hollywood Life ran the video under the headline Derrick Coleman: Watch The Deaf NFL Star’s Inspiring Commercial, and HuffPo crowed Deaf Seahawks Fullback Derrick Coleman Will Inspire You With This Commercial. The comments under the HuffPo article are painfully predictable, with people getting all inspired and teary.

So before I watched the video, I was bracing for inspiration porn. But that isn’t what I found. In fact, I thought that the commercial did an excellent job of showing that among the worst of the barriers that disabled people face are the ways in which we’re ignored, dismissed, and discounted. And, appropriately enough, it’s captioned. Take a look and see what you think:

From the beginning, the ad talks about the ways in which Coleman has been mistreated in his life. The ad doesn’t imply that being deaf is an impediment to being an athlete; in fact, it keeps the focus squarely on the people who discouraged Coleman on the basis of his deafness. “They told me it couldn’t be done. That I was a lost cause. I was picked on. And picked last.”

In fact, rather than saying, “I couldn’t hear” as the reason for his being ignored, the voiceover shifts the responsibility to the people who didn’t know how to communicate with him: “Coaches didn’t know how to talk to me.” To my mind, this is an absolutely stunning line. Whether anyone who put the ad together knows it or not, it comes straight out of the social model of disability. I was so amazed to see that line there that I played the ad several times, just to hear it.

And then, there is the double entendre of using “listen” to mean both “hear” and “take to heart”: “They gave up on me. Told me I should just quit. They didn’t call my name. Told me it was over. But I’ve been deaf since I was three, so I didn’t listen.”

There is great wordplay going on here. Not only does the double entendre work well, but being deaf metaphorically becomes an asset rather than a deficit. It’s his deafness that keeps him from listening to the voices of discouragement and believing in himself. In other words, in the logic of the video, he’s not in the NFL despite his deafness, but because of it. That twist on the mainstream narrative just floors me. And now that Coleman has been able to ignore the dismissals and the discouragement, he can hear the applause, the support, and the people on his side: “And now I’m here, with the loudest fans in the NFL cheering me on. And I can hear them all.” A deaf man saying that he can hear the crowd is a great way to confront the idea that being deaf is always about not hearing at all, and it makes Coleman a person with agency, not a passive victim of fate. He decides when he listens and when he doesn’t. No one else makes that decision for him.

The video ends with a tagline that could easily be read as inspiration porn: “Trust the power within.” Obviously, not all disabled people who believe in themselves experience inclusion, find employment, or get people to cheer for them. But I’m not reading the commercial as an “overcoming disability” story as much as a “don’t let the bastards grind you down” story. It’s not his disability that Coleman has overcome. It’s the microaggressions, the low expectations, and the prejudices of others that he’s pushed out of his head. To me, it’s not what he’s accomplished that is the main thing, but the fact that he stopped listening to the voices of dismissal and pursued something he loves to do.

Whether or not deflecting societal prejudice leads to any sort of tangible reward, simply deflecting it is crucial – and very difficult. No one should despair because of the attitudes of other people, and yet, so many of us do at one time or another. I like the idea of trusting the power within – not because it will help us to overcome all of the massive structural injustices we face, but because it engenders self-respect and self-love.

© 2014 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

The Sins Invalid Film: An Interview with Patty Berne and Leroy Moore

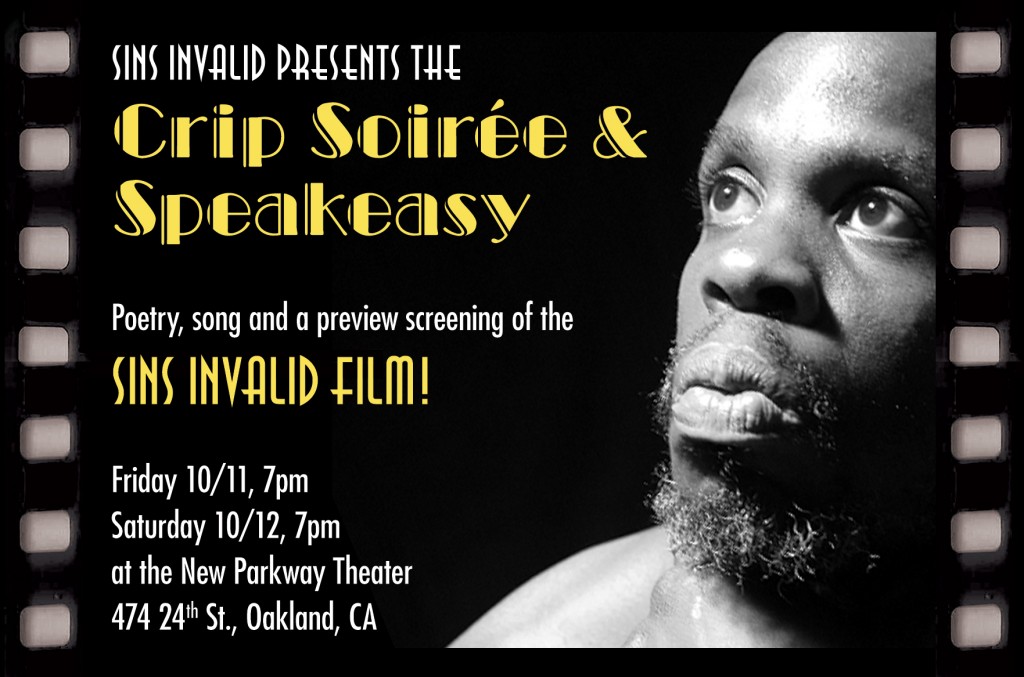

[The graphic consists of the face of a Leroy Moore looking upward and to the left. The left and right borders are drawn to look like the perforations in film negatives. Against a black background, the text reads: “Sins Invalid presents the Crip Soiree and Speakeasy. Poetry, song, and a preview of the Sins Invalid film! Friday 10/11, 7 pm, Saturday 10/12, 7 pm, 474 24th St., Oakland, CA.”]

Sins Invalid is a performance project on disability and sexuality that makes central the work of queer artists, gender-variant artists, and artists of color. Over the past several years, Sins Invalid has been producing a film about its work. The Sins Invalid film will premiere in Osaka, Japan on September 14 and will be shown thereafter in venues around the US.

This past week, I interviewed two of the co-founders of Sins Invalid, Patty Berne and Leroy Moore, about the film, about their work, and about the ways in which Sins Invalid engages issues of disability, sexuality, and justice.

Rachel: What led you to create the Sins Invalid film?

Leroy: We wanted to get Sins‘ artistic and political vision and work beyond the Bay Area. We know that our community has grown nationally, even internationally, and while there’s nothing like a live performance, we wanted to make ourselves as accessible as possible for non-local community.

Patty: The power of the artists’ work really lays in the visual narratives as well as language. It’s important to see disabled bodies (however one defines that) actually embodying power and grace and sexual agency.

Leroy: There’s nothing like having full control of the context and the message both — and we are able to do that on stage and in many ways in film media as well.

Patty: We are being very thoughtful about where and how the film is shown, attempting to partner with community-based organizations to screen it. We are actually having our world premiere in Osaka Japan in a week!

Rachel: That’s so exciting! What will be the venue in Osaka? Where is the film being shown?

Patty: It will be shown as part of the Kansai Queer Film Festival at HEP Hall in Osaka. They invited me to attend and speak as well. They are interested in intersectionality and the potential for allegiance between those doing queer organizing and disability organizing. I’m specifically going to address relationships between gender justice and disability justice.

As a power chair user, I must admit to being very nervous about the ableist air transportation system. But I think it’s an amazing opportunity for disability justice frameworks to go international and for us to build relationship with queer folks with disabilities in Japan. And, it’s a particular honor for me, as I’m Japanese American. (My mother is from Kamakura and immigrated here in the 1940′s.)

Rachel: I’m glad you’re able to avail yourself of this opportunity. Intersectional discussions that include disability are crucial. As I watched the film, I found myself very interested in the process of how you put it together. When did you begin, and what was the process like as it unfolded?

Leroy: We began the film process in 2007 and have accumulated approximately 100 hours of footage.

Patty: As Leroy said earlier, we decided to document the work as a way to spread our vision and begin these conversations in broader sectors. Film has SUCH a broad reach. And as I said earlier, the visual narratives are as powerful as our language. But we had no idea what we were getting into really! I have so much respect for filmmakers! The medium is resource intensive and relatively unforgiving.

We’ve worked with 3 editors over the course of the 5 years, and finally really clicked with one in the last push toward completion.

Rachel: I’m so impressed both by the quality of the art depicted and by the film itself. It is all so beautifully done. Could you each speak to the ways in which the art of Sins Invalid serves the cause of disability justice, particularly in terms of disability and sexuality?

Patty: Thank you for appreciating the work! We live in a very visual age, where we are inundated, saturated by imagery. But most of that imagery reflects systems of oppression and the violence that supports it, slickly produced and packaged so that we consume it without reflecting on what narratives we are ingesting.

We decided to produce performance with high artistic merit because, as artists, that is important to us, but also because we are aware that disability imagery is perpetually used to reinforce our own oppression — charity programs like the MDA Telethon, the specter of the ghastly cripple as in David Lynch films, the tragic crip who serves the higher purpose through suicide as in Million Dollar Baby…

We need images of the truth — that we are powerful and complex and fucking HOT — not despite our disabilities but because of them!

In any movement, there is a need for artists to reflect the reality of the communities, and I think that’s what we’re doing. It’s also our responsibility to reflect the political imagination for what liberation could look like, so we seek to do that as well.

I think movements need a variety of formations — organizations who organize its base, think tanks and scholars and media, policy makers, cultural workers… And I like to think that Sins is doing that cultural work

We focus on disability and sexuality with in a disability justice framework specifically because sexuality is a human right, yet it is one of the most painful ways that we are dehumanized. We are neutered in the public eye (at least in this national context). We recognize our wholeness — including our lived embodied experience and our sexuality — and want to reflect that wholeness.

Leroy: I wanted to add that typically we see sexuality as something we do individually and privately, and we don’t usually see its impact on community. Sins breaks up the idea that sexuality is just an individual activity but brings sexuality into the conversation as a political issue to include as part of justice work. After all, it’s part of our oppression.

Rachel: Yes. One of the most powerful things about Sins Invalid is that it celebrates that disabled people have a lived experience of the body — that our bodies are not inert or inanimate. Given that human beings live in bodies, showing our lived experience is crucial for asserting our humanity.

With regard to justice work, what are the commonalities that you see in the struggle for social justice among marginalized peoples — particular among people of color, trans* and genderqueer people, disabled people, and queer folk — and how does Sins Invalid speak to these commonalities?

Patty: There are many commonalities and points of distinction. One of the primary commonalities is that a tactic of oppression used against all of us is that the oppression has been inscribed on our very skins — that our oppressions have been naturalized as a by-product of having a particular body — so that people think that what is difficult about being gender non-conforming, for example, is being in a non-conforming body, as opposed to being in a system of gender binary and heteronormativity. Or that what is difficult about being disabled is needing an accommodation, as opposed to living within ableism.

Another point of overlap is that our sexualities have been demonized and seen as vile or dangerous, and used as a way of engendering fear of us. Relatedly, our communities’ reproductive rights have been attacked through eugenic practices and programs.

All of the oppressed communities that you identified — communities of color, disability communities, trans/genderqueer communities, queer communities — we are all living within a white, able-bodied, heteronormative patriarchal capitalist context and struggle daily to live safely, with dignity. We each have struggles specific to our own experience of oppression, certainly, but the various systems of oppression reinforce each other and all manifest into all of our communities.

Leroy: And beyond a shared oppression, all of our communities have a rich culture — arts, music, poetry — and through our creation we can learn about each other and how we have each celebrated our own existences and spoken out against injustice. For example, there is a community of queer black women in the Blues that survived “isms” and created strategies for living and amplifying their artistic voice, and I think all communities can learn from that.

Rachel: I agree. One of the things that I appreciate about the work you do is that you go beyond critique into talking about how life can and must be. Along these lines, what kind of impact do you hope the film will have?

Patty: I think we are hoping for folks with disabilities who may not have thought about themselves as beautiful or sexy to see themselves in our work and to see their beauty. And for folks who may be functionally disabled but did not want to identify themselves as disabled due to stigma to perhaps feel a bit safer in rethinking the rigid line separating disabled from able-bodied. And for folks who love the work to move resources toward disabled artists!

And more deeply, to change the public debate about disability and sexuality so that it is a given that we have sexual agency, and that it is recognized that as people with disabilities we are also black and brown and queer and genderqueer and that we are not trading one identity for another. So that when we have a conversation about disability and sexuality, we are necessarily discussing our need for deinstitutionalization so that we can express our sexuality. So that when we discuss disability, we are necessarily addressing the incarceration of black men and the treatment of disabled prisoners. Does that make sense?

Rachel: Absolutely.

Patty: Our hope is that the film humanizes us — all of us.

Leroy: We hope that it will open doors of the heart and mind about what cultural work can look like, to go beyond identity politics alone to witness the diversity and strength of our communities. We hope that the film will be an educational tool for youth with disabilities, especially youth of color.

I hope that the film contributes to a cultural critique about people with disabilities and how we are represented in the media.

Patty: We are developing a study guide so that people can read articles or poems and have discussions in their own settings reflecting on the film and what it evokes for them.

Rachel: I hope that all of the work you’re doing will get people talking. Where will the film be screened, and where can people purchase a copy?

Leroy: We are trying to get into film festivals around the country and partnering with colleges and community based groups everywhere to get the film out initially. We are new members of New Day Films, who will be supporting our distribution. Pretty soon our film will be available for individual purchase at http://www.newday.com!

And in the Bay Area, folks should come out for our Crip Soiree and Speakeasy on October 11th and 12th at the New Parkway Theater in Oakland. You can get tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com/event/444189.

And if you are in Japan, go to the Kansai Queer Film Festival . Patty will be in Osaka screening the film and discussing our work on Sept. 14th! Sins goes international!

Patty: If anyone is interested in bringing the film to their campus or group, feel free to contact us at info@sinsinvalid.org. Or if you want to purchase an individual copy before New Day has it, drop us a line at info@sinsinvalid.org.

Rachel: Thank you both for taking the time to talk about Sins Invalid. Much success to you!

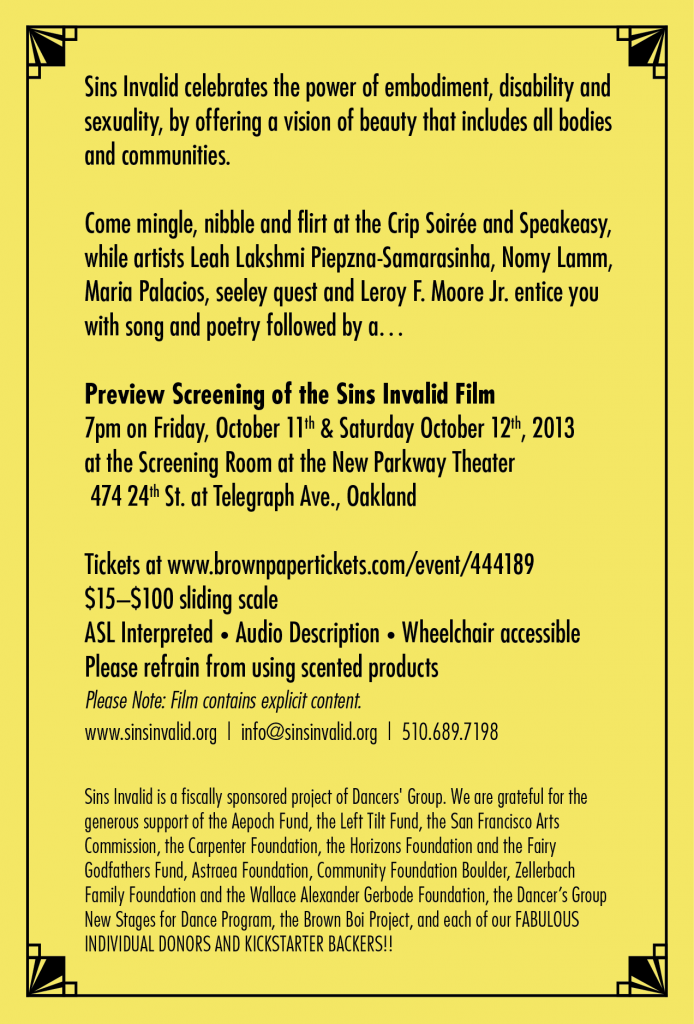

[Against a yellow background bordered by black lines with diamond designs at each corner, the text reads: “Sins Invalid celebrates the power of embodiment, disability and sexuality, by offering a vision of beauty that includes all bodies and communities.

[Against a yellow background bordered by black lines with diamond designs at each corner, the text reads: “Sins Invalid celebrates the power of embodiment, disability and sexuality, by offering a vision of beauty that includes all bodies and communities.

Come mingle, nibble and flirt at the Crip Soiree and Speakeasy, while artists Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Nomy Lamm, Maria Palacios, seeley quest and Leroy F. Moore, Jr. entice you with song and poetry following by a…

Preview screening of the Sins Invalid Film

7 pm on Friday, October 11th and Saturday, October 12th, 2013

at the Screening Room at the New Parkway Theater, 474 24th St. at Telegraph Ave., Oakland

Tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com/event/444189, $15-$100 sliding scale

ASL interpreted – Audio Description – Wheelchair accessible

Please refrain from using scented products

Please note: Film contains explicit content.

www.sinsinvalid.org | info@sinsinvalid.org | 510.689.7198

Sins Invalid is a fiscally sponsored project of Dancers’ Group. We are grateful for the generous support of the Aepoch Fund, the Left Tilt Fund, the San Francisco Arts Commission, the Carpenter Foundation, the Horizons Foundation and the Fairy Godfathers Fun, Astraea Foundation, Community Foundation Boulder, Zellerbach Family Foundation and the Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation, the Dancer’s Group New Stages for Dance Program, the Brown Boi Project, and each of our FABULOUS INDIVIDUAL DONORS AND KICKSTARTER BACKERS!!”]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Disabled People As A Test of Character: The Guinness Commercial

Okay, so. Guinness has a rather, shall we say, problematic new ad that features a bunch of guys in wheelchairs playing basketball. And when I say problematic, I mean that it makes me want to mutter expletives under my breath. Watch, listen, and be appalled:

The ad begins with a basketball flying in slow motion above a basket. Repetitive piano music plays – the kind that creates the score for “inspirational” stories of all kinds. The next several seconds of the video show six guys in wheelchairs playing basketball. You see them rolling down the court. Some of them crash into each other, fall over, and get back up. One guy scores a basket and high-fives another guy. Another guy scores a basket. Then, one of the players stands up and say, “You guys are getting better at this! Yeah! Next week, buddy!” Then, all but one of them stand up out of their wheelchairs and head for the exit, with the person in a wheelchair going with them.

The voiceover says, “Dedication. Loyalty. Friendship. The choices we make reveal the true nature of our character.”

The ad ends with all of the guys having a Guinness in a bar. The Guiness ad reads “Guinness. Made of More.”

When I first saw this ad, I thought it was just going to be an inspiration-porn kind of thing, with a good serving of “Look at what tough men they are! And they love Guinness! Tough men love Guinness! Even if they’re in wheelchairs! Roar!” Bad enough, but not surprising.

But then one of the guys gets up out of his wheelchair. And I’m all WTF?

And then four more guys get up out of their wheelchairs. And I’m even more all WTF?

So let’s see what we’re supposed to make of this video:

1) Real friends buy expensive lightweight wheelchairs so that they can play basketball with their disabled friends. Is this even a possibility for most people? No. No, it’s not.

2) Real friends (or is it just real men?) can somehow learn how to use a manual wheelchair well enough to play basketball in it. Is this even a possibility for most people? No. No, it’s not.

3) The one disabled person must be called out as an object of charity with “Next week, buddy!” Under no circumstances is anyone to say, “Next week, everyone!” Because, apparently, the other five guys just showed up for the disabled guy’s sake, not because they all wanted to play basketball together. Awesome.

4) Disabled people must be called “buddy.” Apparently, this is affectionate. If you’re five.

5) Including a disabled person become an opportunity to show what fine, noble, humanitarian people we are.

What can I say? If “the choices we make reveal the true nature of our character,” and we choose to make a disabled person the occasion for humanitarian sentiments by calling him out as an object of charity with a diminutive generally reserved for children — well, that makes our choices very suspect indeed, doesn’t it?

Look. The strange and surreal nature of the whole commercial aside, its message is about inclusion, and that would be great, except that the message is being handled in all of the wrong ways. Not only is the charity model so very, very outdated, but the whole idea of putting people on a pedestal for being inclusive is tiresome.

Including people is the right thing to do. Period. It’s not a test of character. It’s not an opportunity for humanity and heroism. It’s just basic ethics. Very basic. Very ordinary. Very pedestrian. No big deal. No need to put it on a billboard. No need to construct a commercial around it.

Inclusion is just another word for basic human rights.

Violating basic human rights? That shows something about your character.

Supporting basic human rights? That’s just something you’re supposed to do.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

You Can’t Undo Body Shame by Shaming Other Bodies

I recently ran across the following rather problematic graphic:

Source: Imgur

[The graphic consists of a photograph of Morpheus from The Matrix. The text at the top reads: “What if I told you” and the text on the bottom reads, “size doesn’t matter as long as you’re healthy.” At the bottom right, the text reads “memegenerator.net.”]

I love “size doesn’t matter” memes. I truly do. In fact, I love body positivity memes in general.

But this meme — well, I don’t love this meme.

If the meme had stopped with “size doesn’t matter,” I’d be all for it. Fat acceptance is awesome. But the whole meme is conditional; as soon as you tack on “as long as,” the attempted radical acceptance of the fat body becomes not quite so radical. A condition is in place for accepting one’s fat body. One has to be “healthy.”

What does that mean to most people? A “healthy” person is one who is physically fit and eats “nutritious” foods. A “healthy” person is free from chronic illness and disability.

So, apparently, size matters terribly if, say, you’re chronically depressed, and food is one of the few things you find pleasure in, and you eat lots of chocolate and don’t exercise. Then, somehow, if you’re fat, you should feel badly about your body — as though your body is the visible indicator of a moral failing.

Size also seems to matter if you take medication that causes you to gain weight easily, or if your body is naturally fat and you don’t really care about working out, or if you gain weight easily because your mobility is very limited, or if you’re poor and don’t have many food choices at all.

Size seems to matter very much if you don’t meet the standard of “health” — a standard that is just as narrow and socially constructed as the standard of “beauty.”

This sort of judgment isn’t restricted to this meme. Judging people according to size is being displaced in favor of judging people according to health. This switch is apparent on sites like Healthy is the New Skinny (which asserts that “You are the most beautiful when you are happy and healthy”) and on Facebook pages like The Love Your Body Project (which “was created to help women (and men) feel healthy and powerful and glow in their own skin!”). Among a number of people working to accept their bodies, “healthy” is the new standard for judging themselves.

I fail to see how continuing to hold bodies to impossible standards is progress. Bodies are not always “healthy,” and they will not always stay “healthy.” People get sick. They get disabled. Bodies fall apart. Inevitably. If your body hasn’t become ill or disabled yet, mazel tov to you, but this kind of thinking will not serve you on the day that it does. And it certainly doesn’t serve anyone whose body does not meet the socially constructed standard of “health.”

I fundamentally don’t understand the need to Other people in this way. Must we human beings always feel good about ourselves at the expense of others? Is it really necessary to say, “I might be fat, but at least I’m healthy” when that statement has the rather loud and unsubtle subtext of “unlike those people over there”?

There is no need to shame bodies in this way. No need at all. No one should be asked to apologize for living in a body.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

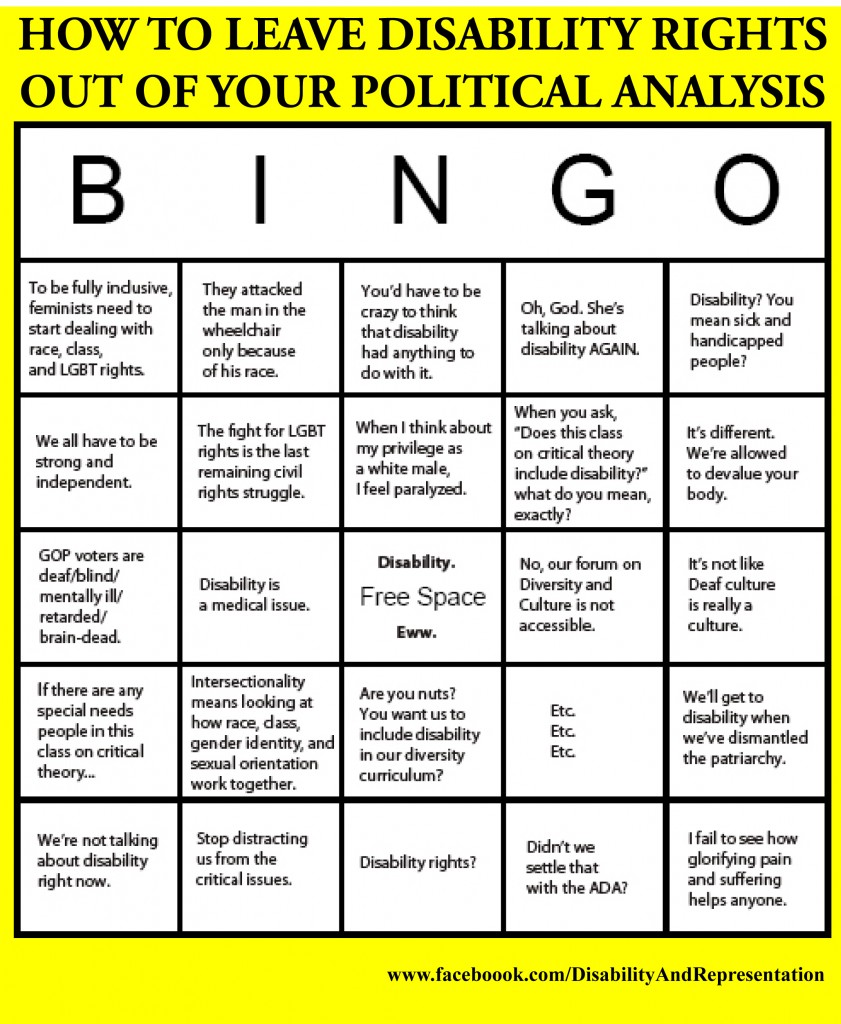

How to Leave Disability Rights Out of Your Political Analysis

[The graphic is a Bingo card with 25 squares.

Title: How to Leave Disability Rights Out of Your Political Analysis

Top row:To be fully inclusive, feminists need to start dealing with race, class, and LGBT rights.

They attacked the man in the wheelchair only because of his race.

You’d have to be crazy to think that disability had anything to do with it.

Oh, God. She’s talking about disability AGAIN.

Disability? You mean sick and handicapped people?

Second row: We all have to be strong and independent.

The fight for LGBT rights is the last remaining civil rights struggle.

When I think about my privilege as a white male, I feel paralyzed.

When you ask, “Does this class on critical theory include disability?” what do you mean, exactly?

It’s different. We’re allowed to devalue your body.

Third row: GOP voters are blind/deaf/mentally ill/retarded/brain-dead.

Disability is a medical issue.

Free Space: Disability. Eww.

No, our forum on Diversity and Culture is not accessible.

It’s not like Deaf culture is really a culture.

Fourth row: If there are any special needs people in this class on critical theory…

Intersectionality means looking at how race, class, gender identity, and sexual orientation work together.

Are you nuts? You want us to include disability in our diversity curriculum?

Etc. Etc. Etc.

We’ll get to disability when we’ve dismantled the patriarchy.

Last row: We’re not talking about disability right now.

Stop distracting us from the critical issues.

Disability rights?

Didn’t we settle that with the ADA?

I fail to see how glorifying pain and suffering helps anyone.

The text below the graphic reads www.facebook.com/DisabilityAndRepresentation.]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

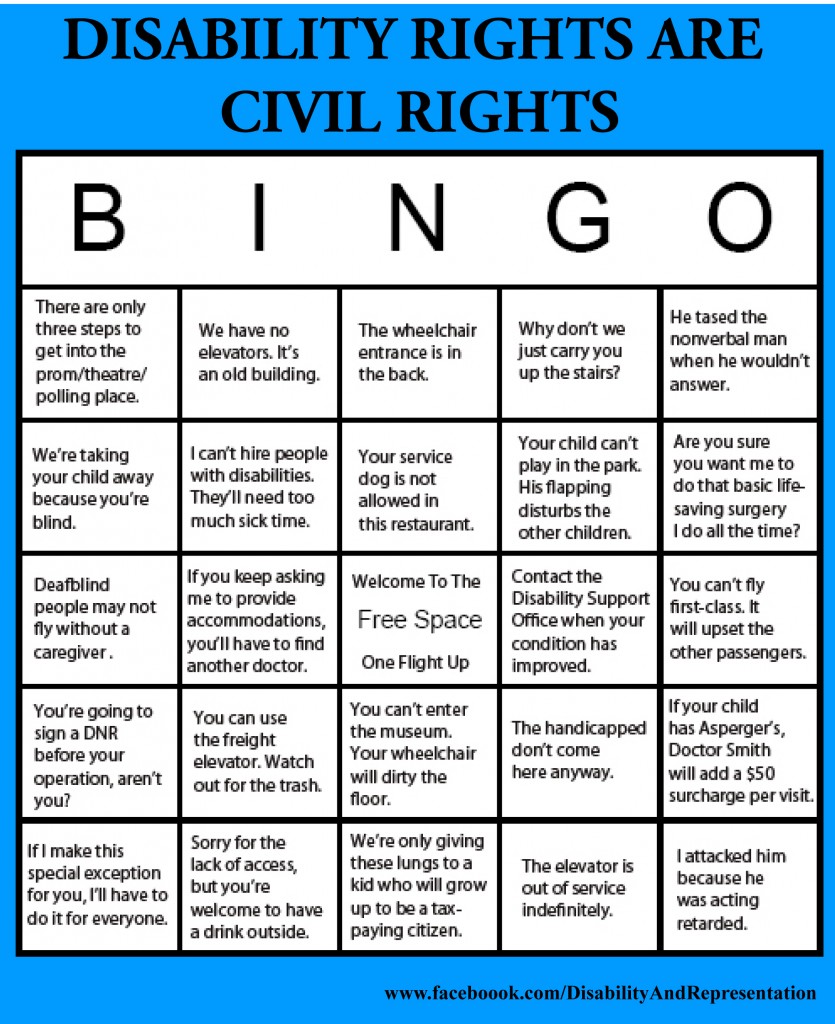

Disability Rights are Civil Rights

Imagine that you were simply living your life and someone attempted to exclude you from a public park. Or took your child away from you. Or urged you to sign a Do Not Resuscitate Order. Or told you to use the back door to a theatre. Or told you that you couldn’t come into a restaurant.

Now imagine that someone said or did any one of those things only because of your race. Or only because of your sexual orientation. Or only because of your ethnic origin. Or only because of your gender identity. Or only because of your socio-economic class.

You’d consider it a civil rights violation, wouldn’t you? And you would be right.

These are exactly the things that disabled people experience, every day, only because they are disabled.

Think disability isn’t a civil rights issue? Think again.

[The graphic is a Bingo card with 25 squares.

Title: Disability Rights are Civil Rights

Top row: There are only three steps to get into the prom/theatre/polling place.

We have no elevators. It’s an old building.

The wheelchair entrance is in the back.

Why don’t we just carry you up the stairs?

He tased the nonverbal man when he wouldn’t answer.

Second row: We’re taking your child away because you’re blind.

I can’t hire people with disabilities. They’ll need too much sick time.

Your service dog is not allowed in this restaurant.

Your child can’t play in the park. His flapping disturbs the other children.

Are you sure you want me to do that basic life-saving surgery I do all the time?

Third row: Deafblind people may not fly without a caregiver.

If you keep asking me to provide accommodations, you’ll have to find another doctor.

Welcome to the Free Space. One Flight Up.

Contact the Disability Support Office when your condition has improved.

You can’t fly first-class. It will upset the other passengers.

Fourth row: You’re going to sign a DNR before your operation, aren’t you?

You can use the freight elevator. Watch out for the trash.

You can’t enter the museum. Your wheelchair will dirty the floor.

The handicapped don’t come here anyway.

If your child has Asperger’s, Doctor Smith will add a $50 surcharge per visit.

Last row: If I make this special exception for you, I’ll have to do it for everyone.

Sorry for the lack of access, but you’re welcome to have a drink outside.

We’re only giving these lungs to a kid who will grow up to be a tax-paying citizen.

The elevator is out of service indefinitely.

I attacked him because he was acting retarded.

The text below the graphic reads www.facebook.com/DisabilityAndRepresentation.]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

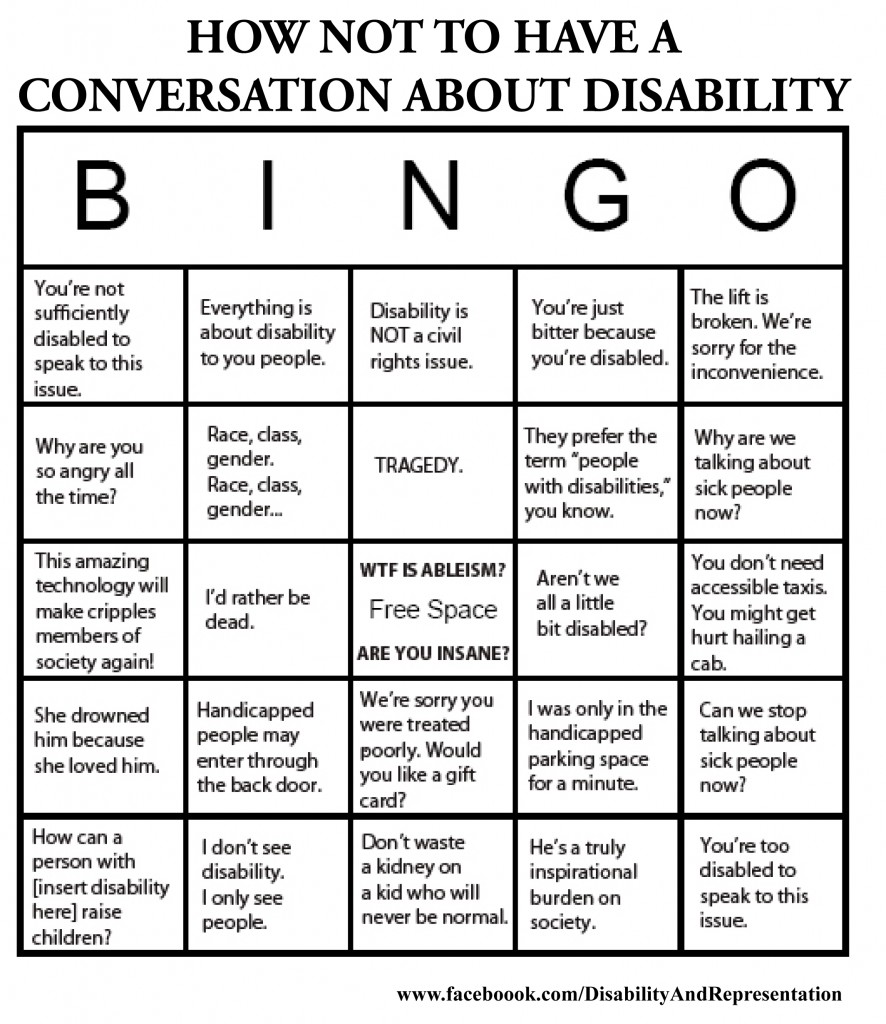

How Not to Have a Conversation about Disability

[The graphic is a Bingo card with 25 squares.

Title: How Not to Have a Conversation about Disability

Top row: You’re not sufficiently disabled to speak to this issue.

Everything is about disability to you people.

Disability is NOT a civil rights issue.

You’re just bitter because you’re disabled.

The lift is broken. We’re sorry for the inconvenience.

Second row: Why are you so angry all the time?

Race, class, gender. Race, class, gender…

TRAGEDY.

They prefer the term “people with disabilities,” you know.

Why are we talking about sick people now?

Third row: This amazing technology will make cripples members of society again!

I’d rather be dead.

Free space: WTF is ableism? Are you insane?

Aren’t we all a little bit disabled?

You don’t need accessible taxis. You might get hurt hailing a cab.

Fourth row: She drowned him because she loved him.

Handicapped people may enter through the back door.

We’re sorry we treated you so poorly. Would you like a gift card?

I was only in the handicapped parking space for a minute.

Can we stop talking about sick people now?

Last row: How can a person with [insert disability here] raise children?

I don’t see disability. I only see people.

Don’t waste a kidney on a kid who will never be normal.

He’s a truly inspirational burden on society.

You’re too disabled to speak to this issue.

The text below the graphic reads www.facebook.com/DisabilityAndRepresentation.]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

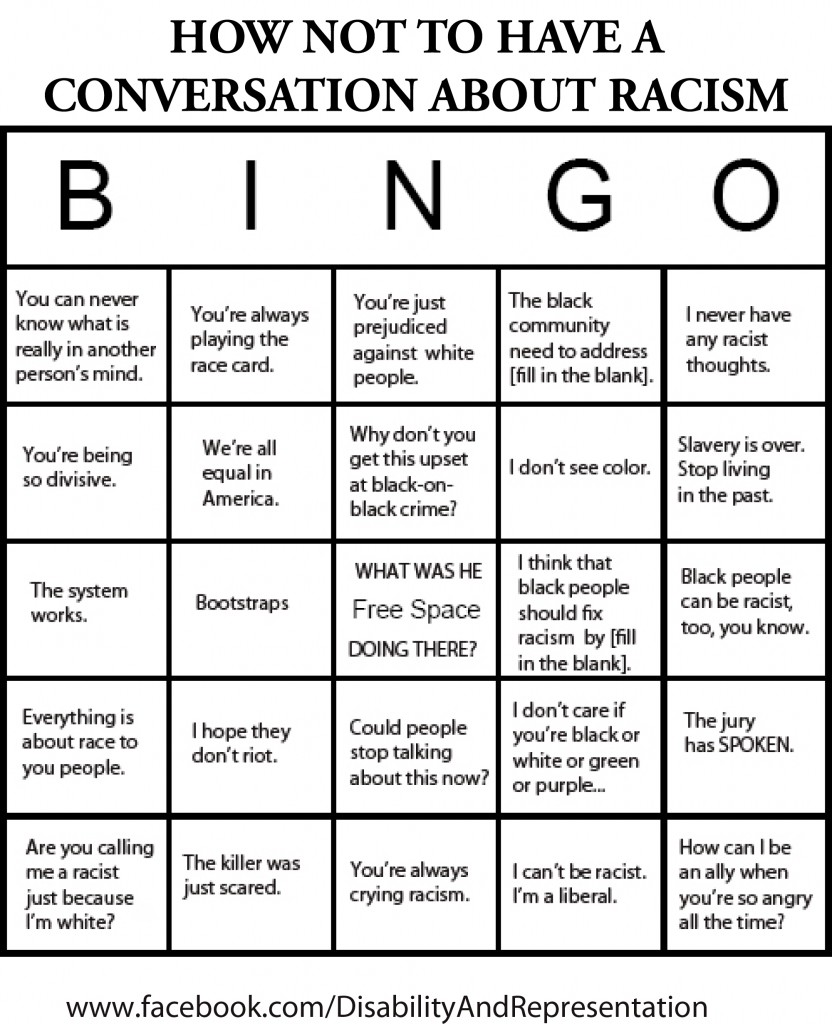

How Not to Have a Conversation about Racism

[The graphic is a Bingo card with 25 squares.

Title: How Not to Have a Conversation about Racism

Top row: You can never know what is really in another person’s mind.

You’re always playing the race card.

You’re just prejudiced against white people.

The black community needs to address [fill in the blank].

I never have any racist thoughts.

Second row: You’re being so divisive.

We’re all equal in America.

Why don’t you get this upset at black-on-black crime?

I don’t see color.

Slavery is over. Stop living in the past.

Third row: The system works.

Bootstraps.

Free space: What was he doing there?

I think that black people should fix racism by [fill in the blank].

Black people can be racist too, you know.

Fourth row: Everything is about race to you people.

I hope they don’t riot.

Could people stop talking about this now?

I don’t care if you’re black or white or green or purple…

The jury has SPOKEN.

Last row: Are you calling me a racist just because I’m white?

The killer was just scared.

You’re always crying racism.

I can’t be racist. I’m a liberal.

How can I be an ally when you’re so angry all the time?

The text below the graphic reads www.facebook.com/DisabilityAndRepresentation.]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg