Petty Cruelties

Today I was talking to a friend who lives on disability and has been homeless for several months. He told me a story that simultaneously made me angry and broke my heart.

The other day, while he was standing on the street, he saw something that delighted him, and he wanted to get a picture of it. He was getting ready to use his smartphone to take the photo when a couple of women started talking in very loud voices about how he should not have a smartphone.

“That man is begging and he has a $400 smartphone? How dare he! That’s just wrong. He shouldn’t have anything like that!” And on and on.

In point of fact, he got the phone for $70. But really, who cares what it cost? It doesn’t matter, because in the eyes of some people, poor folks should be completely destitute before they deserve anything. And even if they were completely destitute, you know that these very same self-righteous good citizens would still do nothing to help. If my friend were on the street with nothing but the clothes on his back, they’d spit at him and call him a lazy bum because being poor is, in their eyes, some sort of moral and social crime.

I am a very shy person when it comes to initiating social interactions. But if I’d been standing there while these women started in on this subject, you could not have shut me up. I’d have told them where to shove it and invited them to take their privileged asses down the road.

This is the mentality that keeps people on the street. You want homeless folks to get housing and jobs? How are they supposed to do that without a phone, without decent clothing, without food, without shelter, without all of the things that they need?

People and their petty cruelties just break my heart sometimes. My friend is a kind and decent person in a terrible situation who just wanted to take a photo of something that made him happy. And random people passing on the road — people who have never spoken to him, people who have never given him anything, people who have all the food and shelter they could ever need — couldn’t even let him have a happy moment. They had to open their mouths. They had to say something. They had to fuck it up. They couldn’t have a moment of consideration for someone else and just keep their damned mouths shut.

There is so much suffering out there, and the systemic problems are so huge. When people try to find some measure of happiness in the midst of it all, why try to take that from them?

I despair of humanity at times. These cruel, petty microaggressions just tear me up. And then I look at my friend, who has more decency and kindness than almost anyone I’ve ever met. People like him keep me going when I think that the world is beyond redemption.

I hope I help to keep him going, too.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Ableist Language in Social Justice Spaces: It’s Not Just About the Words

One of the most difficult things for me about hanging out in Internet social justice spaces is the sheer amount of ableist language that gets thrown around there. Some of us point out the language and ask people to refrain from using it, but it rarely works. There are days that, if I wanted to, I could make a full-time job out of calling out every iteration of “He’s insane” and “What a moron” that people trot out to describe putatively “normal” folk who hold egregious views or dictate bad social policy. The pushback is usually along the lines of “We have more important things to do than talk about words” and “You’re asking too much” and “We shouldn’t have to protect you from nasty speech on the Internet.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about these kinds of discussions, because they all follow a similar pattern, and they all tend to focus on language. I find that focus enormously frustrating because, for me, it is never just about language. It’s about the level of devaluation and disability hatred that lies beneath the language. Much of this devaluation and hatred are unintentional, but that doesn’t make their impact on people’s lives any less.

The devaluation is acceptable and normal. People who are of non-normative intelligence or ability (narrowly defined) are simply considered less-than, so it’s the height of insult to call someone “stupid” or “a moron” or “a person with a low IQ.” Likewise, people with severe disability are considered less-than, so it’s perfectly acceptable to respond to an argument you don’t agree with by saying “If you believe that, you shouldn’t go out without a carer.” (Yes, I have heard someone say that in a social justice space. I could almost see the sneer.) When I hear these kinds of words, it’s the hatred and devaluation I’m responding to, because it’s everywhere, and it has a concrete impact on people’s lives, including my life, the lives of people I love, and the lives of people I serve.

Much of the time when we talk about ableism in social justice spaces, it’s not in the context of violence, lack of services, the valuation of ability, the construct of normalcy, hate crime, institutionalization, homelessness, inaccessibility, isolation, and a number of other issues that intersect in all kinds of ways with race, queer, class, and trans* issues. The fact that disability isn’t incorporated into these spaces as its own social justice issue leads to discussions on language that can end up feeling very theoretical and rather precious. The issue really isn’t about language at all, but about the pervasive impact of the kinds of hatred that the language betrays. If there is no discussion about the impact of that hatred, though, then questions of language lose their grounding.

For me, language discussions are always about concrete things. We think in language, and it forms how we address the problems that face us. It’s the problems that concern me — and the ways in which language reinforces them, frames them, and limits our ability to look at them.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

The Stories We Tell: Coming to Terms with PTSD

One of the ways in which I navigate the cacaphony of competing discourses about disability, mental health, and just about everything else is to remind myself that we humans are always storytelling and that these discourses are just a series of stories. Along with eating, sleeping, and breathing, storytelling is what we do. Certainly, some things — like the sheer physicality of our bodies — aren’t just stories, and yet, we interpret even these things with stories about them.

I’ve been thinking a lot about stories lately — about the stories I tell about myself, about the stories I tell about other people, about the stories people have told about me, about the stories the media tells about everyone. I don’t fault people for telling stories. It’s what we do in order to makes sense out of our existence. As Arthur Frank writes, we are beings who, in order to make life habitable, must tell stories from the narrative resources available to us:

“To say that humans live in a storied world means not only that we incessantly tell stories. Stories are presences that surround us, call for our attention, offer themselves for our adaptation, and have a symbiotic existence with us. Stories need humans in order to be told, and humans need stories in order to represent experiences that remain inchoate until they can be given narrative form… We humans are able to express ourselves only because so many stories already exist for us to adapt, and these stories shape whatever sense we have of ourselves… ” (Frank 2012, 36)

One of the things that comforts me in this life, especially when I feel barricaded in by the absurdities of the things that people say, is to remember that we can rewrite these stories. If we are all inveterate storytellers — incorporating pieces of different narratives and creating new narratives from what exists — then we can always reinterpret and rewrite our stories. We are always free to engage that process. The problem is that stories often masquerade as fact, and we feel cut off from rewriting them at all.

To say that a story isn’t fact doesn’t mean that it’s entirely fiction. The stories that people tell always have truths in them somewhere. But they are not necessarily truths about the purported subjects of the story. A story about me might contain no truths about me at all. It might contain truths about the storyteller’s fears. It might contain truths about the storyteller’s trauma. It might contain truths about the storyteller’s desire for power.

There are two sets of stories that plague me. One set consists of the negative stories that people have told about me or about people like me. These stories tend to be pathologizing. Sometimes, they are so ubiquitous that it is difficult to have the strength to analyze, reinterpret, rewrite, and rethink them. But I’m coming to see that it’s the stories that I tell myself about myself that are the most troubling. Some of these stories incorporate the larger narratives, sometimes by design and sometimes unintentionally. Others are a rebellion against the larger narratives. It would be impossible to avoid responding to these narratives in some way.

These days, there is one story of mine whose validity I’ve been calling into serious question. It has to do with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

I’ve been dealing with PTSD for nearly my whole life. It began over 50 years ago, when I was four years old. I wasn’t diagnosed until I was in my thirties, and that diagnosis was like the heavens opening up and the angels singing. I know that it sounds like a strange thing to say about a PTSD diagnosis, but how else can I describe the way in which the PTSD markers — the core narrative elements of the PTSD story — mirrored my own story so well? Suddenly, someone was narrating my story in a way that I recognized.

Over time, I learned to navigate and handle PTSD triggers. I learned to distinguish between a trigger and actual danger. I learned how to detach and breathe and not react when the catastrophic thinking started. I got very good at it.

And it worked for a long time — until a whole new level of protracted trauma came along, triggered the old trauma, and gave me a whole new set of things to heal from. It took me a long time to recognize the new trauma as trauma, even though it went on for 11 years. My husband and I moved to California this year, just to get away from it.

In order to cope all these years, I’ve told myself a story about how well my old adaptive patterns were working. And so, in true PTSD fashion, I went back to the story that had served my survival as a child — the story in which I was always the person who has it together, who figures it out, who doesn’t show weakness, who helps other people, who never asks for help, who is always on top of things, and who is somehow beyond regular, garden-variety human needs. In other words, I have spent the past decade or more dealing with PTSD by telling myself a story that am not traumatized. Not really. Maybe I used to be. But surely, not anymore.

Right.

These days, that story is showing itself to be largely fiction. It began a few days ago, when my husband left for a visit to the east coast. I felt tremendous sadness. I looked at the sadness and thought, “What is that doing there?” I started to ask the sadness what it was trying to show me. And within three days, I got the message: my body is absolutely racked by trauma. For the first time in my life, I am fully inside my body and it is incredibly painful. The level of stress, of sheer physical tension, of never feeling at ease, of never feeling safe is constant. I look at some of the things I do, and I see how hypervigilant I am.

For instance, there is the way I sit on the sofa and use the computer. Here is a picture of my sofa:

[The photo shows a picture of a futon with a blue spread in a mandala design. There are four white pillows along the back and some beige carpeting is visible in front. A small wooden end table is visible to the right.]

[The photo shows a picture of a futon with a blue spread in a mandala design. There are four white pillows along the back and some beige carpeting is visible in front. A small wooden end table is visible to the right.]

It’s a futon that doubles as a guest bed. It looks very beautiful and comfortable, doesn’t it? But do I sit on this futon comfortably, leaning against the pillows, relaxing? No, I don’t. I sit on the edge, next to the table, with one foot on the ground, looking like I’m ready to fight an intruder who is about to mercilessly fuck with me.

You can see why my story about not being traumatized isn’t exactly working.

One of the things I have noticed recently about my attempt to fend off PTSD is that I have bifurcated the telling of my stories into public and private. In my public writing, I will talk about disability quite openly. But privately, I rarely talk about it at all. For instance, I wrote to my regular doctor today about whether she could help with a letter of medical necessity for a service dog for PTSD, and her response was along the lines of “We’ve never talked about your PTSD. We really should.”

It’s true. We never have. I wrote her back and basically said, “We’ve never talked about most of my disabilities. We really should.”

I’ve been seeing this doctor since May. She knows about my auditory processing disorder. She knows about the problem with my hip. But she does not know about my Asperger’s diagnosis. She does not know about my recent diagnosis of mixed receptive-expressive speech disorder. She does not know about my dypraxia. She does not know about my severe vestibular issues. She does not know about my sensory processing disorder. She only learned about my PTSD today, and I’ve been dealing with that since I was four.

Why hadn’t I talked to her? Partly, it’s that I’m so wounded by many of the assumptions that people make about my disabilities that I almost can’t bear it anymore. I have had so many bad experiences. And of course, the PTSD gets in the mix there, because the PTSD says, “Right. Don’t talk about it. Don’t show any vulnerability. Act like you’re fine.”

I told her why I hadn’t raised the issue. And her response was, “I understand your hesitation.”

So it looks like we’ll be having that conversation after all. I will also be seeing someone for EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapy. And I’m making tracks about getting a service dog. I can’t continue to talk about disability publicly and pretend privately like everything is fine.

I sometimes wonder whether passing as nondisabled isn’t sometimes an expression of PTSD. I mean, who wants to deal with all of the crap that gets thrown at us around disability if they can help it? Over the past couple of years, I’ve done everything I can to avoid as much of it as possible. But now I’m tired and my body hurts. It’s time to start telling the people I know in my daily life, not just in my writing.

Perhaps it’s safer to talk with all of you about it. If you’re reading this piece, it’s because you have some connection to the world of disability. But most people do not. And they’re the ones I have to start addressing, even when I feel like one more refusal, one more ignorant response, one more uncaring word is going to break my heart.

References

Frank, Arthur. W. “Practicing Dialogical Narrative Analysis.” In Varieties of Narrative Analysis, edited by James A. Holstein and Jaber F. Gubrium, 33-52. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2012.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Displays of Power

I went down to the Santa Cruz Wharf today and spent some time people-watching. I am often observing people. I am always fascinated by the ways in which they interact with one another. Today, two scenarios caught my eye:

Scenario 1: When I came onto the wharf, a bicyclist was riding up to the toll booth, getting ready to exit. He was a young man of about 25. As soon as he got to the toll booth, the automatic gate arm came down and blocked his path. He stopped short and fell off his bicycle. To my left, I heard someone laugh. I looked over and saw a young man laughing and pointing at the guy who was struggling to get up. The bicyclist finally got on his bike and rode away.

Scenario 2: At the end of the wharf, a young girl of about five was chasing pigeons. She ran around, looking for pigeons, everywhere she could. She took great glee in shaking her paper bag at them and frightening them so that they flew away. She showed no signs of tiring of the game.

What these two scenarios have in common is someone taking power over a creature in a weaker position. One person took power by laughing at someone who had fallen. The other — a small, vulnerable creature herself — took power over creatures even smaller and more vulnerable.

I try to stay away from questions of what human beings are “really” like, because I’m not sure you can separate the power relationships in a society from what human beings are “really” about. In our society, at any rate, it seems that people are trained up to take power over someone they perceive as vulnerable.

I think this is why so many people have such a deep and abiding fear of becoming disabled. I don’t think it has as much to do with disability in the body as with perceived vulnerability. What happens to me if I’m dependent on others? Will I really be able to depend on them? Or will they take advantage of my vulnerability?

There are very fine people who don’t take advantage of vulnerability. These are the folks who want to raise people up in dignity rather than lord power over them. I try to find those people and hold them very close. Because the other kind will wreak havoc with your life.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

You Don’t Have to Thank Me For Doing the Right Thing

Over the past several months, I’ve become aware of how much I say thank you on any given day. In many ways, it’s just second nature. I was raised to say please and thank you and you’re welcome and excuse me, to hold doors open for people, and to generally look for ways to be courteous. It’s ingrained in me to say thank you any time anyone does anything for me at all.

The odd part? I thank people just for doing what they themselves expect as a matter of course.

In a post today, Dave Hingsburger at Rolling Around in My Head talks about this phenomenon, noting that he thanks people for what they take for granted every day. They assume the right to pass through space without barriers. Dave thanks people for making it happen for him.

Like Dave, I don’t think that showing my appreciation of what people do for me is wrong, per se. Courtesy has its place, and exchanging thanks is way of saying, “I see you and I appreciate you.” But when there is no even exchange, and when people feel a little too much gratitude for basic things they should expect as human beings, there is a problem.

The question of saying thank you has been coming up a lot for me lately around the issue of space. When I first arrived in Santa Cruz, I spent a fair amount of time weaving around people on the sidewalk. In the rurals of New England, where I come from, people tend to give each other a wide berth. But oddly enough, here in mellow hippie crunchy Santa Cruz, it’s very different. Most people have a strangely aggressive sense of space. Perhaps it’s just the fight for space in an urban area, where people have to stake out their claims. I’m not sure. But I can’t begin to count the number of times I’ve had people practically dare me to get out of their way on the sidewalk or assume that I was going to walk right into the street to make room for them. Since I’ve started using a cane, I’ve become very sensitized to it.

The first few times it happened, I thought that the folks who passed a little too close to me just had a poor sense of where they were. But then it kept happening every day, to the point that it became statistically impossible that so many people had spatial orientation issues. There is a strange sort of game that people play around space, and for a while, I found myself saying thank you to people for making space for me — even when they were taking up more than their fair share of space and impinging on mine. While other people were expanding their sense of space, I was making it a virtue to get small and take up less. And then I was saying thank you for people letting me by.

After a couple of experiences in which people became actively hostile, I decided to take a different approach. I decided that I had to stop bobbing and weaving. I had to stake out my claim — just my claim, without challenging the claim of anyone else.

So now, when I walk down the street and I see people taking up the majority of the sidewalk, I don’t walk onto the street. I keep to my trajectory, I hold my head up, and I show that I expect them to get out of the way. They generally do. And no, I don’t thank them. They’ve done the right thing. They’ve taken up their space and no more. Things are as they should be.

I shouldn’t have to thank them any more than they should have to thank me. Of course, I have my own set of privileges. People thank me all the time for doing the right thing, and I need to start speaking back to that, too. If I shouldn’t have to be constantly thanking people for doing the right thing, other people shouldn’t have to constantly be thanking me either.

The issue comes up most often in my interactions with people on the street. There is almost always someone sitting on Pacific Avenue with a sign asking for spare change, and I’ll sometimes ask if I can get the person some food. The responses to these offers vary. Some people just say no and ask for money. I’ll usually give a few dollars.

Most of the time, though, people take me up on the offer. And most of the time, people are very thankful — thankful in a way that pains me. It’s not that people are wrong for saying thank you. It’s that the whole damned deal is wrong.

I recognize where some of it comes from. I’ve had times when I’ve felt so demeaned and so ignored that any kindness filled my soul with gratitude. It wasn’t so much a choice to feel that way as a moment of sheer relief that I didn’t have to have my defenses up for five minutes. When you’re in that position and someone comes along to do a kindness, it’s like manna falling from heaven. There’s a gratitude — not just for the person, but for whatever God or cosmic power or act of fate dropped that person into your path.

I watched this kind of gratitude and relief come over the face of another person yesterday. I was talking to a guy trying to get into rehab and a shelter. He looked so surprised — no, shocked — that I was being kind. It was as though he were looking at a mirage. When I asked him what he wanted to eat, he mumbled something about beggars not being allowed to be choosers.

When I assured him that, in fact, he could choose, he asked me for an egg salad sandwich. And as I was going to get it for him, he said, “You’re an angel.”

That’s when something broke in me. An angel? Just for getting a man an egg salad sandwich? No. I couldn’t let it pass. I said, “No, I’m really not.”

As tired as I am of thanking people for doing the right thing, I’m even more tired of having an excess of gratitude come at me for doing the right thing. I don’t mind being thanked as a courtesy, and I don’t mind expressions of gratitude to God and the universe for whatever good things come along, but I’m tired of getting kudos for treating people like human beings. The gratitude that comes my way says so much more about the world we live in than it says about me. It’s not that I’m an angel. It’s that the world we live in is exceptionally harsh and uncaring. You do the right thing — which is what we’re supposed to be doing in the first place — and it looks exceptional only by comparison.

No one should go hungry.

No one should be spat on.

No one should be harassed or assaulted.

No one should be ignored.

No one should have to thank someone profusely for space, or access, or bread, or kindness.

All of these things are a matter of justice, not a matter of charity.

So I need to stop constantly thanking people for doing what’s right. And I need to let people know that they have a God-given right to expect me to do right by them. I don’t need their thanks. I just need to do the right thing.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

A Rant to My Fellow Activists Who Do Anti-Oppression Work and Ignore Disability

Dear Activists Who Wax Eloquently About The Importance Of Intersectionality In Anti-Oppression Work:

I need to make a request. I’ll try to keep it brief and I’ll do my best to be clear about exactly what I mean.

PLEASE STOP FUCKING IGNORING DISABILITY.

I’ve noticed that many of you complain loudly and vehemently that feminism doesn’t do intersectionality right because it leaves out race, class, LGBT issues, genderqueer issues, religion, ethnicity, and body size. I agree. I completely agree. It’s why I left feminism in disgust some time ago. So imagine my utter fucking surprise when I notice that, oh hell, there is no room for me to agree at all because, as a disabled woman, I haven’t even been invited into the discussion.

I mean, really. It’s provoking to watch you call out feminists for not doing intersectionality right while you leave disabled people out of it altogether. While you keep chanting “race, class, gender” over and over, congratulating yourselves on how inclusive you’re being, you’re leaving out one-fifth of the population.

Disability winds through every other form of oppression. There are disabled people of color, disabled working class people, disabled poor people (lots), disabled LGBT people, disabled genderqueer people, disabled fat people, disabled religious people, disabled people of every ethnicity, and disabled people who experience every form of oppression that human beings can perpetrate. I know the thought that you could become one of us in a millisecond scares the absolute living fuck out of you, but seriously, deal with your fears already because they are not helping us. Start grokking the fact that disabled people are being assaulted, killed, institutionalized, and otherwise having their civil rights violated every goddamned day.

Because in case you haven’t gotten the memo, disability is a civil rights issue.

When people have their children taken away because they’re disabled, it’s a civil rights issue. When people are refused entrance into a restaurant or a theatre or a public park, it’s a civil rights issue. When people are counseled to die rather than live, it’s a civil rights issue. When people are consigned to poverty because of the ways their bodies look and function, it’s a civil rights issue. When people are assaulted, spit on, and killed because they’re disabled, it’s a civil rights issue. When people live in isolation even within communities that talk about oppression and social justice, it’s a civil rights issue.

Every time you fail to acknowledge our presence, it only increase our invisibility. So really, how the hell are we disabled people supposed to join you in doing anti-oppression work if you keep treating us like the embarrassing relative no one talks about?

Allies have one another’s backs. No way in hell am I saying, “I’m your ally, but when it comes time for you to fight for me, I’m on my own.”

Fair is fair.

Reciprocity forever.

In solidarity,

Rachel

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

Practicing Random Acts of Solidarity

Today, I was on the bus to work, sitting in the accessible section at the front, when a woman got on with her support person. I might not have noticed that the woman was atypical at all except that after she had retrieved her Metro ticket from the machine, she gave it to the blond twenty-something woman behind her. Then she walked over, sat next to me, and said hello. Her support person was across the aisle and behind us.

The woman was intellectually disabled and likely in her 40s. She was very friendly and very open. I felt immediately at home with her. She smiled at me and asked how I was doing. Our conversation went something like this:

Woman: Hi, how are you?

Me: I’m doing great. And you?

Woman (smiling and giving me a thumbs up): Great! Where are you going?

Me: I’m going to work. And you?

Woman (smiling and giving me a thumbs up): We’re going to the mall!

Me: Oh! The mall will be fun!

Woman (smiling and giving me a thumbs up): Yeah!

Me (smiling and giving her a thumbs up): Awesome!

At this point, a man across the aisle leaned over to me, held out his hand for me to shake, and introduced himself. I realized right away that they were together and that he was intellectually disabled as well. He seemed a bit younger than the woman, heavy set, and gentle. We shook hands and smiled at each other.

I was thoroughly enjoying myself and feeling at ease in a way that is unusual for me in a public place. There was something that captivated me about these two people. Their openness and their kindness were such a welcome relief from the harshness of the world. There was a decency and a presence about them that were palpable. In a flash, I realized how much trust it was taking for them to open up a conversation with me, a perfect stranger. I thought about the sheer difficulty of trying to make “normal” conversation. I thought about how hard they were working to try to “fit in.” I thought about their support person, who was sitting in back of them and looking quite bored.

I continued talking with the man. I asked whether he were going to the mall too, but he said no, that he was getting pizza. We started chatting a bit about how much we like pizza and how what a nice day it was, and so forth, when the support person interrupted from afar and said:

“We’re not going to the mall. We’re going for pizza.”

It was so jarring. Her tone was abrupt and corrective. I thought about how many times her client, over the course of 40-odd years, must have been told she was wrong. And maybe she’d made a mistake about the mall, but so what? There was so much right about her. She was succeeding at being welcoming, at being cordial, at being engaging, at being lovely. It really saddened and angered me that her support person was interrupting all that.

As though that weren’t enough, the support person started trying to address me and talk about her clients and what they were doing. She wasn’t joining in our conversation. She was attempting to interrupt our conversation and to have a conversation over them. It was terribly rude.

I got the sense that, in the face of her clients having a conversation with someone who was very clearly enjoying their company, she didn’t quite know what to do. It was as though her whole know-your-place world was being overturned. After all, while talking with the man and the woman, I wasn’t being patronizing and I didn’t give the impression of wanting to change my seat. In fact, I was subverting the thinking that says that those were my only options.

At this point, there were only the four of us on the bus. And for a very brief moment in time, three of us had done something deeply subversive: we had dismantled the hierarchy that said that I ought to establish my perceived normalcy over them and that they ought to accede to it.

It must have been quite confusing for the support person: except for my cane, I looked perfectly “normal.” So what I was doing having such a great time with these people as though they were my equals?

I immediately registered her attempt to take my attention from them, and I was having none of it. So I did something that I very rarely do with anyone: I ignored her. I kept my attention focused on the man and the woman like a laser beam. I was going to keep that hierarchy overturned until I got off the bus.

It really wasn’t a conscious decision. My focus just stayed with them and would not be moved. A kind of stubbornness kicked in. I simply would not let anyone hijack the conversation: not when we all were enjoying it, not when they had extended their trust to me, not when someone was trying to put them in their place.

So we kept talking until my stop came. And when it was time to get off the bus, I said to them both, “Well, it was great meeting you and talking to you. Have a wonderful day!”

I hope they did. I hope our little revolution on the bus rocked their world, as it had mine.

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

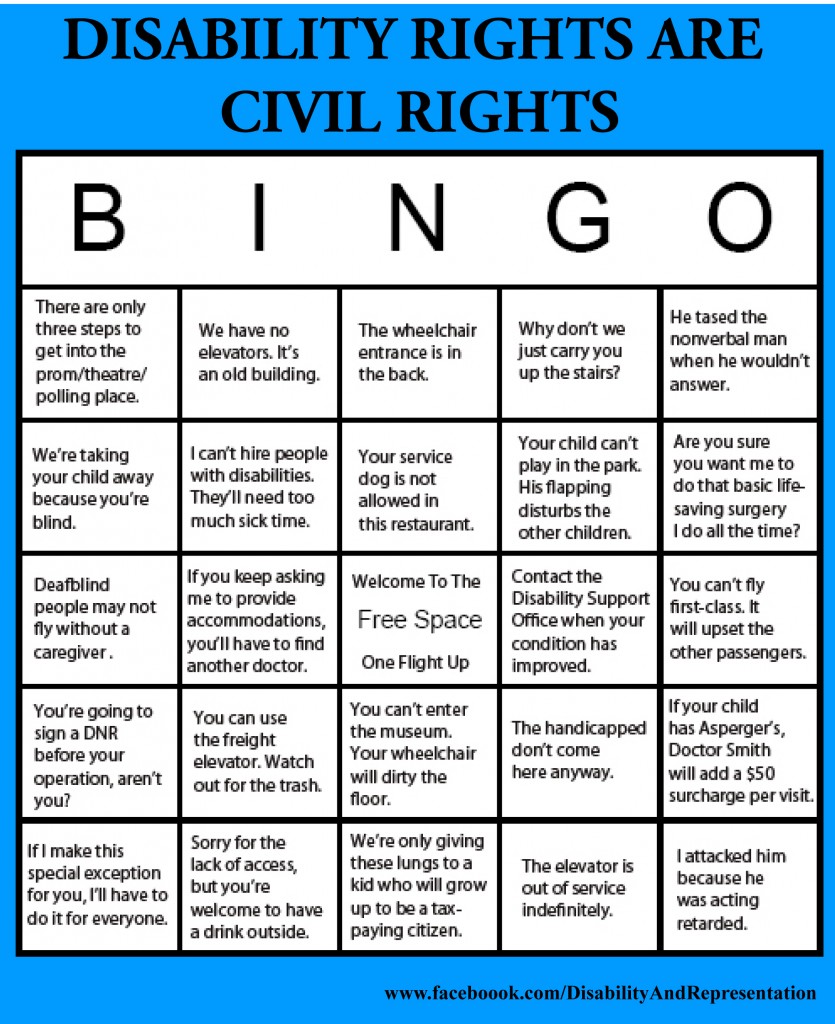

Disability Rights are Civil Rights

Imagine that you were simply living your life and someone attempted to exclude you from a public park. Or took your child away from you. Or urged you to sign a Do Not Resuscitate Order. Or told you to use the back door to a theatre. Or told you that you couldn’t come into a restaurant.

Now imagine that someone said or did any one of those things only because of your race. Or only because of your sexual orientation. Or only because of your ethnic origin. Or only because of your gender identity. Or only because of your socio-economic class.

You’d consider it a civil rights violation, wouldn’t you? And you would be right.

These are exactly the things that disabled people experience, every day, only because they are disabled.

Think disability isn’t a civil rights issue? Think again.

[The graphic is a Bingo card with 25 squares.

Title: Disability Rights are Civil Rights

Top row: There are only three steps to get into the prom/theatre/polling place.

We have no elevators. It's an old building.

The wheelchair entrance is in the back.

Why don't we just carry you up the stairs?

He tased the nonverbal man when he wouldn't answer.

Second row: We're taking your child away because you're blind.

I can't hire people with disabilities. They'll need too much sick time.

Your service dog is not allowed in this restaurant.

Your child can't play in the park. His flapping disturbs the other children.

Are you sure you want me to do that basic life-saving surgery I do all the time?

Third row: Deafblind people may not fly without a caregiver.

If you keep asking me to provide accommodations, you'll have to find another doctor.

Welcome to the Free Space. One Flight Up.

Contact the Disability Support Office when your condition has improved.

You can't fly first-class. It will upset the other passengers.

Fourth row: You're going to sign a DNR before your operation, aren't you?

You can use the freight elevator. Watch out for the trash.

You can't enter the museum. Your wheelchair will dirty the floor.

The handicapped don't come here anyway.

If your child has Asperger's, Doctor Smith will add a $50 surcharge per visit.

Last row: If I make this special exception for you, I'll have to do it for everyone.

Sorry for the lack of access, but you're welcome to have a drink outside.

We're only giving these lungs to a kid who will grow up to be a tax-paying citizen.

The elevator is out of service indefinitely.

I attacked him because he was acting retarded.

The text below the graphic reads www.facebook.com/DisabilityAndRepresentation.]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

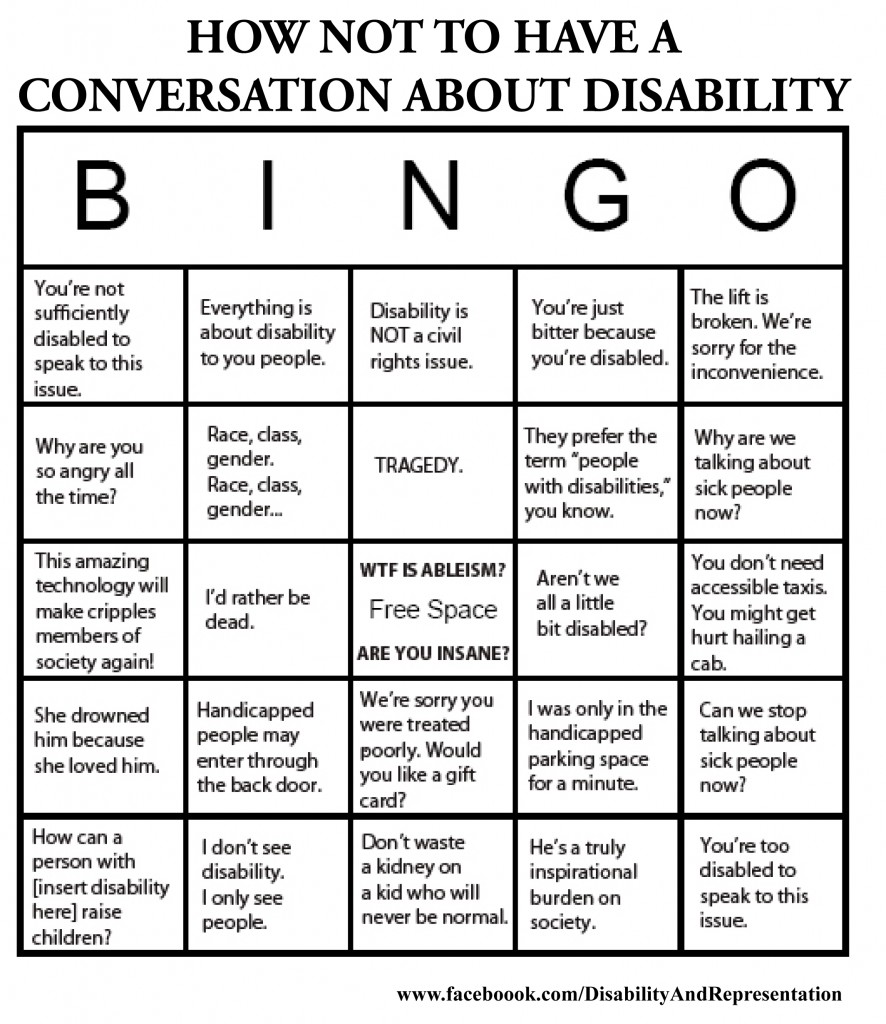

How Not to Have a Conversation about Disability

[The graphic is a Bingo card with 25 squares.

Title: How Not to Have a Conversation about Disability

Top row: You're not sufficiently disabled to speak to this issue.

Everything is about disability to you people.

Disability is NOT a civil rights issue.

You're just bitter because you're disabled.

The lift is broken. We're sorry for the inconvenience.

Second row: Why are you so angry all the time?

Race, class, gender. Race, class, gender...

TRAGEDY.

They prefer the term "people with disabilities," you know.

Why are we talking about sick people now?

Third row: This amazing technology will make cripples members of society again!

I'd rather be dead.

Free space: WTF is ableism? Are you insane?

Aren't we all a little bit disabled?

You don't need accessible taxis. You might get hurt hailing a cab.

Fourth row: She drowned him because she loved him.

Handicapped people may enter through the back door.

We're sorry we treated you so poorly. Would you like a gift card?

I was only in the handicapped parking space for a minute.

Can we stop talking about sick people now?

Last row: How can a person with [insert disability here] raise children?

I don’t see disability. I only see people.

Don’t waste a kidney on a kid who will never be normal.

He’s a truly inspirational burden on society.

You’re too disabled to speak to this issue.

The text below the graphic reads www.facebook.com/DisabilityAndRepresentation.]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg

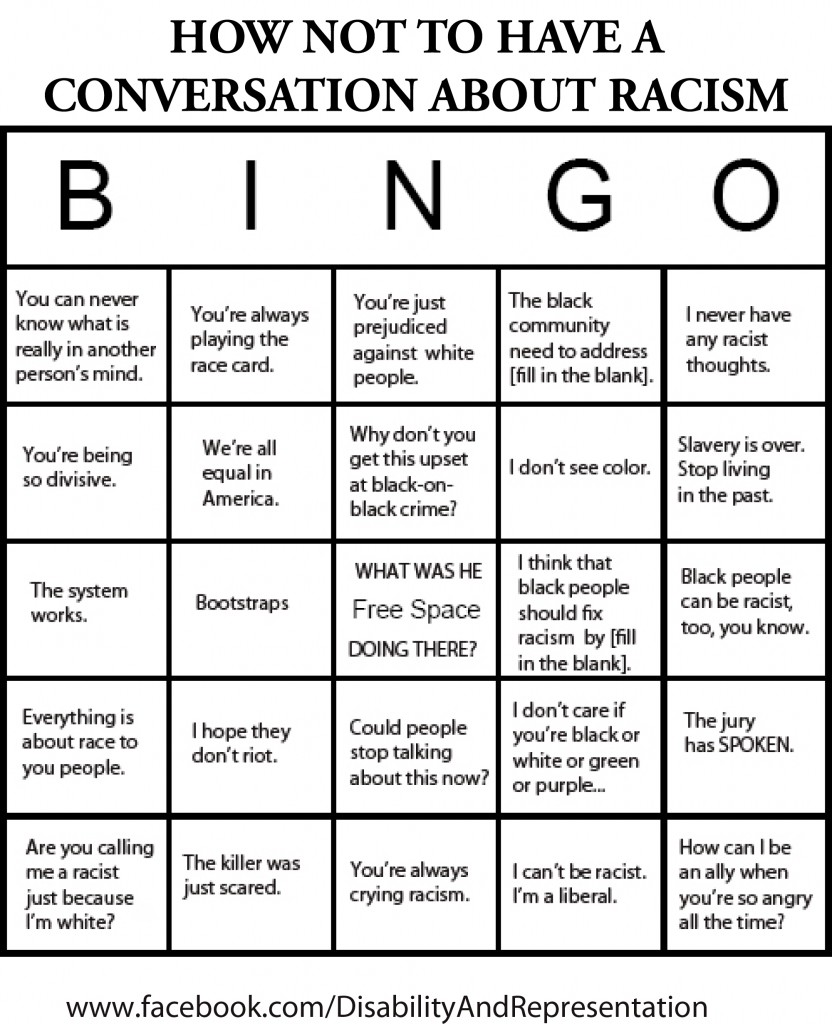

How Not to Have a Conversation about Racism

[The graphic is a Bingo card with 25 squares.

Title: How Not to Have a Conversation about Racism

Top row: You can never know what is really in another person's mind.

You're always playing the race card.

You're just prejudiced against white people.

The black community needs to address [fill in the blank].

I never have any racist thoughts.

Second row: You’re being so divisive.

We’re all equal in America.

Why don’t you get this upset at black-on-black crime?

I don’t see color.

Slavery is over. Stop living in the past.

Third row: The system works.

Bootstraps.

Free space: What was he doing there?

I think that black people should fix racism by [fill in the blank].

Black people can be racist too, you know.

Fourth row: Everything is about race to you people.

I hope they don’t riot.

Could people stop talking about this now?

I don’t care if you’re black or white or green or purple…

The jury has SPOKEN.

Last row: Are you calling me a racist just because I’m white?

The killer was just scared.

You’re always crying racism.

I can’t be racist. I’m a liberal.

How can I be an ally when you’re so angry all the time?

The text below the graphic reads www.facebook.com/DisabilityAndRepresentation.]

© 2013 by Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg